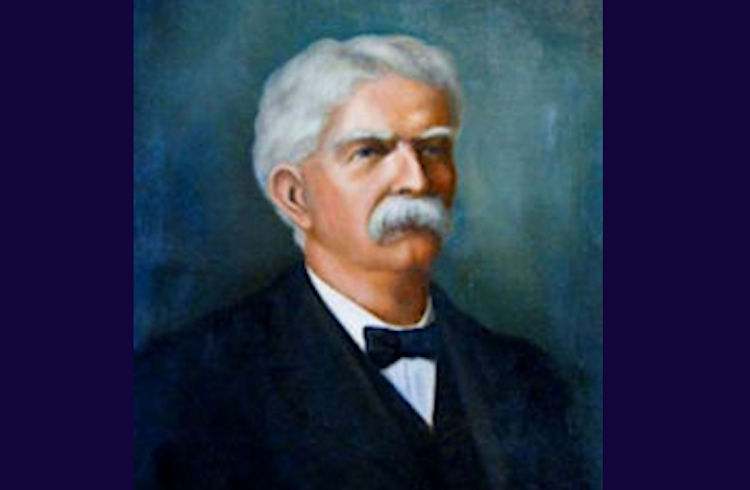

Robert Smith Phifer was born on May 9, 1852 in Charlotte, North Carolina. In 1874 he married Isabella Hunt McGehee and four years later the couple moved to Danville where Mr. Phifer assumed the post of Chair of the Music Department at the Roanoke Female College. The college, which was the predecessor of Averett University, was situated facing Patton Street at the corner of South Ridge Street (then Tazewell Alley, where Biscuitville is located today). The Phifer’s took up residence at 241 Jefferson Avenue.

It was at the Roanoke Female College that the Professor became acquainted with the young Frederick Delius who had come to the college to teach music, despite his parents’ strong objections to pursuing a musical vocation. It was owing to Professor Phifer, who saw real talent and potential in young Delius, that the Delius family were at last persuaded to support their son’s aspirations. Frederick soon after left for Europe to begin his studies, eventually becoming a world-renowned composer.

It was at the Roanoke Female College that the Professor became acquainted with the young Frederick Delius who had come to the college to teach music, despite his parents’ strong objections to pursuing a musical vocation. It was owing to Professor Phifer, who saw real talent and potential in young Delius, that the Delius family were at last persuaded to support their son’s aspirations. Frederick soon after left for Europe to begin his studies, eventually becoming a world-renowned composer.

Besides being a career musician and educator, Professor Phifer was also a hobby naturalist. He knew a great deal about the local flora and fauna and had a great love of sharing that knowledge with others.

Though his health was in decline during the final years of his life, the stroke that took him on September 12, 1910 at the age of 59, was nevertheless unexpected and caused a ripple of sadness throughout the city, but nowhere more particularly so than on the campus of the College where he had devoted so much of his life. Determined that he should be remembered, a group of friends and former students banded together “as the result of a spontaneous desire … to give some expression of … appreciation of him as teacher and friend” to raise funds to erect a memorial in his honor.

On September 24, 1913 that memorial was erected on the grounds of the Sutherlin Mansion.

“The memorial is a hewn granite pedestal surmounted by the grass dial and the indicator, the pedestal being appropriately inscribed in raised letters upon the north face of the imperishable stone.”

Perhaps not so imperishable, though. By 1930 the memorial had become a target of vandalism. “These depredations have resulted in the stone cap being broken. The dial itself has been stolen, leaving nothing but a broken shaft.” To remedy the issue, a squad of West End firemen were given police authority and appointed as caretakers of the Sutherlin mansion property. But the vandals won. The remnants of the sun dial were eventually dismantled and tucked away in the mansion’s basement. In 1950, when a project to restore the grounds was proposed, the issue of the sun dial was raised once more, but the idea of restoring it was ultimately abandoned and the Phifer Memorial, like the man himself, has been all but forgotten (not unlike another missing Museum grounds monument.) We will do our part to memorialize him here.

May the good works of the men and women who have come before us ever be remembered.