Next door to F. L. Douthat, at 135 Holbrook Avenue, lived his four highly-educated, accomplished, and unmarried sisters. It may be presumed that the house was built for them, as they occupied it from the time it was built, around 1908.

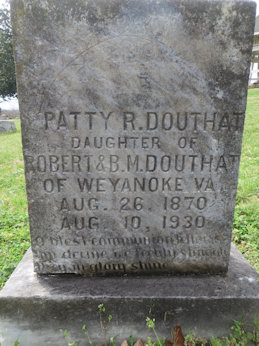

The home was owned by Pattie (Patty) Rudd Douthat, the eldest of the four sisters who lived here (though there were other sisters nearby, including Helen Meade who lived on South Main and Mildred Riddle who lived at 941 Green Street for a time and then on the 700 block of Holbrook Avenue). Pattie was born August 27, 1870, at Weyanoke Plantation on the James River near Richmond, the seventh of twelve children born to Robert and Elizabeth (Bettie) M. Wade Douthat. Pattie was a stenographer and owned a private business located on Market Street in the Masonic Temple building. In 1925, she sold the business, after what papers describe as a “breakdown” and went into retired life, though she continued to speak at engagements on the subject of women in business. She was active in the Epiphany Church, as well as being a member of the Wednesday Afternoon Club and the Business and Professional Women’s Club. She died in her home on August 10, 1930, (just 17 days shy of her 59th birthday) of a stroke that occurred a couple of weeks before. Ownership of the home then transferred to her sister Bettie.

The home was owned by Pattie (Patty) Rudd Douthat, the eldest of the four sisters who lived here (though there were other sisters nearby, including Helen Meade who lived on South Main and Mildred Riddle who lived at 941 Green Street for a time and then on the 700 block of Holbrook Avenue). Pattie was born August 27, 1870, at Weyanoke Plantation on the James River near Richmond, the seventh of twelve children born to Robert and Elizabeth (Bettie) M. Wade Douthat. Pattie was a stenographer and owned a private business located on Market Street in the Masonic Temple building. In 1925, she sold the business, after what papers describe as a “breakdown” and went into retired life, though she continued to speak at engagements on the subject of women in business. She was active in the Epiphany Church, as well as being a member of the Wednesday Afternoon Club and the Business and Professional Women’s Club. She died in her home on August 10, 1930, (just 17 days shy of her 59th birthday) of a stroke that occurred a couple of weeks before. Ownership of the home then transferred to her sister Bettie.

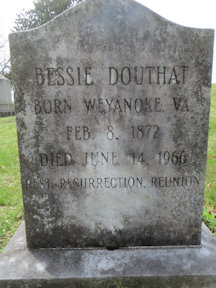

Bettie (Bessie) Douthat was born February 8, 1872 at the family plantation of Weyanoke. Historical records do not indicate an occupation for Bettie, though her death notice describes her as being well-educated, having been taught first by a governess and then continuing her education in Philadelphia. She was a charter member of the Danville Garden Club. Bettie remained in the house for nearly sixty years, taking in lodgers and renting rooms in her large house, until her death in January of 1966 at the age of 98.

Bettie (Bessie) Douthat was born February 8, 1872 at the family plantation of Weyanoke. Historical records do not indicate an occupation for Bettie, though her death notice describes her as being well-educated, having been taught first by a governess and then continuing her education in Philadelphia. She was a charter member of the Danville Garden Club. Bettie remained in the house for nearly sixty years, taking in lodgers and renting rooms in her large house, until her death in January of 1966 at the age of 98.

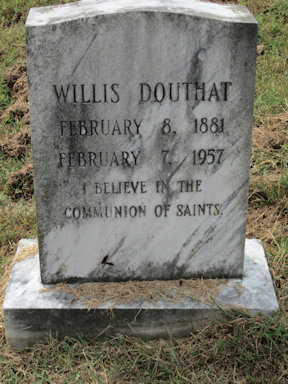

Willis, the second to the youngest of the Douthat siblings, received her early education, as her sisters did, at home with a governess. She then went on to study at the University of Virginia, where she earned a bachelor’s degree before going to England, where she studied at Oxford. Upon returning to the States, she took a position as a school teacher in one of the Danville schools, but later accepted a place in Norfolk, where she spent the remainder of her life, passing away in 1957 of cancer of the liver.

Willis, the second to the youngest of the Douthat siblings, received her early education, as her sisters did, at home with a governess. She then went on to study at the University of Virginia, where she earned a bachelor’s degree before going to England, where she studied at Oxford. Upon returning to the States, she took a position as a school teacher in one of the Danville schools, but later accepted a place in Norfolk, where she spent the remainder of her life, passing away in 1957 of cancer of the liver.

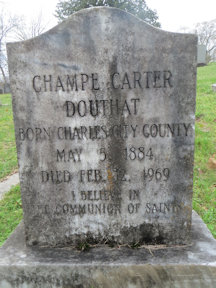

Champe was the youngest of the Douthat sisters, indeed, of the entire brood of Douthat siblings. Champe and Willis, by all accounts, were inseparable. They were educated similarly, attending both the University of Virginia and Oxford together, and both becoming teachers. Champe even followed Willis to Norfolk when the opportunity provided itself to teach there. It was in Norfolk, at Maury High School, that she took the position of head of the mathematics department. She returned to Danville, however, after Willis’s death and resumed her residence on Holbrook Avenue until Bettie’s death in 1966. She afterwards moved to Roman Eagle Nursing Home. In November of 1968, after taking a fall in which she broke her hip, she was sent to Memorial Hospital, where she died of pulmonary edema three months later.

Champe was the youngest of the Douthat sisters, indeed, of the entire brood of Douthat siblings. Champe and Willis, by all accounts, were inseparable. They were educated similarly, attending both the University of Virginia and Oxford together, and both becoming teachers. Champe even followed Willis to Norfolk when the opportunity provided itself to teach there. It was in Norfolk, at Maury High School, that she took the position of head of the mathematics department. She returned to Danville, however, after Willis’s death and resumed her residence on Holbrook Avenue until Bettie’s death in 1966. She afterwards moved to Roman Eagle Nursing Home. In November of 1968, after taking a fall in which she broke her hip, she was sent to Memorial Hospital, where she died of pulmonary edema three months later.

* * *

These outlines we write of the people who shaped Danville’s history before us are based on the facts of their lives that we can pull from censuses and directories and, when we are lucky, obituaries, but it is rare to find anything broader and more nuanced that would offer an idea of the characters and personalities of these people. In the case of the Douthat sisters, we are fortunate to have the account of their nephew, the famous writer, Julian R. Meade, whose own mother, Helen, was an elder sister of the Douthats. What follows is an excerpt from the book that made him famous, I Live in Virginia. Parentheses are ours.

These outlines we write of the people who shaped Danville’s history before us are based on the facts of their lives that we can pull from censuses and directories and, when we are lucky, obituaries, but it is rare to find anything broader and more nuanced that would offer an idea of the characters and personalities of these people. In the case of the Douthat sisters, we are fortunate to have the account of their nephew, the famous writer, Julian R. Meade, whose own mother, Helen, was an elder sister of the Douthats. What follows is an excerpt from the book that made him famous, I Live in Virginia. Parentheses are ours.

After supper, if Mother did not go to my aunts’ houses, those four clannish ladies were likely to come up our brick walk between the scraggly box. The slightest excuse would cause a convention of five sisters. If one was feeling poorly, the other four had to nurse her. If one was going away for as much as a day, the other four made farewell visits which ended with much kissing of turned cheeks and suitably affectionate embraces. If one had a birthday, the other four came to celebrate. Sometimes the excuses were rather flimsy. On Thursday afternoons Mother said, “This afternoon we’re going after chickens and eggs. They’re selling cheap at Ringgold.” ‘We’, needless to say, meant the closed corporation of herself and the other four girls, as she termed the rest of this quintet.

“But, Mother,” I said perversely, “considering the gas you buy to go ten or twelve miles in the country, it would be much cheaper to call the grocer.”

“She never admitted that Chicken and Egg Thursdays were adored because she and the sisters squeezed into one automobile and rode away, laughing and talking and commiserating among themselves. What was said during those rides could be imagined but never known. Only when we drew up rockers on the porch after supper could I join the gatherings which brought me such endless delight.

The oldest of the aunts (Pattie) settled herself in her chair and viewed me with glee as I hung intent upon every word she spoke.

“I know what you’re up to, you rascal. You’re just waiting to put me in your crazy notebook. I’ve heard about that notebook. See if I care though! Put everything about my old fat self and see if I care! Go right ahead. Your mother may object but I—”

Her voice was soft and pleasant. Listening to her and half-listening at the same time to my mother and the youngest aunts on the other side of the porch, I knew why so many people’s voices in New York grated so dreadfully on my nerves and why the flat, careless speech of many Southerners was always noticed. How pretty she was as she sat there chattering and smiling! She was lovelier as she grew older: I saw the lights in her gray hair, the radiance of her large brown eyes, the serene expression of her well-shaped face. It would be fine, I thought, if more people could grow old as charmingly.

“May I even tell about the false teeth?” I asked, causing Father, who was a curious mixture of sprightliness and gravity, to give me the stern look of disapproval which I had received just as often after becoming twenty-one as before.

“Tell all about the teeth,” she said, chuckling gaily. “Big horse teeth, little baby teeth, temporary teeth, musical teeth, all of them. I don’t care a rap, even if your father does think I’m a terrible woman.”

This interest in artificial masticating devices irked the depths of Father’s soul. But he could never have sh-sh-shd my oldest aunt. Her performance was inevitable. While Father twitched and fidgeted in indignation, I laughed until, literally and truly, I rolled upon the floor in a paroxysm of uncontrollable mirth.

… as the conversation swerved to loftier topics of church affairs, invalids, and second mortgages on Main Street homes, I moved my foot-stool to a point from which I could study the character of a lady with sharp features, keen brown eyes, and wavy gray hair. This was the second and most straightforward member of this corporation (Bettie) which my oldest aunt ruled like an easy-going queen.

“Why don’t you come to church m ore often?” she said swiftly, fastening upon me a formidable glare.

“I have so little time and, anyway—”

“You have plenty of time to do what suits your taste. You have plenty of time to waste on all sorts of books. I’ll bet you’ve been reading some more books by that Peterkin woman and such—”

“Mrs. Peterkin is one of the people I like best. Don’t say anything about her character, because I won’t listen.”

“Well, anyway, you could come to church if you wanted to. You don’t support the church, so you can’t expect the church to support you. Who’s going to bury you?”

“Really, I haven’t made any plans.”

“Well, I’ll tell you. You’ll have a pauper’s funeral. You never lift your finger for Epiphany so you can’t expect Epiphany to put you away in Green Hill as fine as a Vestryman. I don’t know what the country is coming to, anyway. Do you know you ought to give a tenth to your church? The Bible says you’ve got to tithe.”

“Nobody resented her frankness. She was a law unto herself: only the oldest aunt could rebuke her and even the queen handled her with care. She would flay you alive with words and, then, as soon as you were sick for as much as a day, she arrived somewhat disdainfully and deposited a bag of grapefruit or a bowl of wine jelly on the table by your bed. “Your mother looks worn to a frazzle,” she would observe. “How long are you going to lie in that bed?”

Somehow, either because her candor was a family tradition or because it was felt that a drab career is supposed to make one slightly caustic, she was conceded the privilege of speaking and acting as she chose. She asked us why, what, whom, where, and when we were going to certain events; how little or how much money we earned and such; whether we knew that it was bad to have rich demands when we ourselves were as poor as Job’s turkey.

Her probing was incessant and yet for us there was no comeback, no return. So frequently did she slip out in the morning, never telling anyone where she was going, that one of the young sisters accused her good-naturedly of leading a double life; she grinned at this but she did not say where she went. Her financial status was a mystery, “Well, I can’t afford to ride a street car,” she would say, or “I don’t know how I’ll pay my taxes”, or, “This is the fifth repair for this coat but I can hardly buy coal.” Her affairs were inscrutable: she was one of those people who want the accounts of other lives but keep their own secrets well concealed. It seemed strange that she should be one of the sisters at all since she was always an independent figure … One of the rare occasions when I heard her commit herself to any extent was once when some ladies were praising the rich interests of small town life. She listened to the Pollyannas as long as she could and then she said, “I’m glad to know you’re all so happy. I’m bored a good part of every day, bored to death.”

Whatever one said about her was always ended by saying, “She’s good as gold.” And that was as true as it could be about anyone. Behind her mask and bluff she was loveable, kind, and marvelously honest…

Moving my seat again, this time to the swing near the younger aunts, I realized that there were little unions within the larger union. The two youngest aunts were inseparable; you never saw one without the other; they were about the same size and, except for the fact that one was darker than the other, they might have been thought of as twins. They taught in the same Virginia school, shared a house and automobile, divided all expenses, and, if ever they fussed, nobody knew about it except themselves.

When I sat by them I was sure of hearing something about our public schools which, according to Jefferson tradition, were so liberal and free. What did I hear? All that my young aunts retained of the James River pattern for womanhood was a gentle manner, the soft voices and a very broad “a”. Teaching had not prevented them from reading and thinking. They dared to say what they chose and, I daresay, if they had not been exceptionally fine teachers, they would have been disposed of as were so many other liberal-minded persons who strayed into our standardized public school system which still seemed to regard Administrators and a certain type of Baptist deacon as one and the same. Their mortal enemies were not children opposed to learning but System, Methods, and the Guardianship of Public Morals.

They like to tell about a friend who was so learned and capable that she could defy certain gentlemen as though she had never heard of Servants of the State.

“The Board tells her that she must use certain books and follow certain prescribed methods and outlines. If she thinks the rules antiquated and useless, she pipes right up and says she’ll use the best books she can find and teach as she sees fit. If anybody else defied the gentlemen, they’d be dumbfounded, but what can they do with a high school teacher who has live with French people and been honored by the French government for her mastery of the language?”

“She is one in a thousand, though,” I said, thinking of the “French” pedagogs I knew, who followed the Board rules scrupulously, murdering their subject in the process. “So many teachers I know have no opinion of their own, and if they did have any, they wouldn’t want the public to know they did.”

“If you are going on with teaching, said the dark-haired aunt, who was considered to be witty and handsome, “you must go into college work. But I hope you won’t be a teacher. What was it that Willa Cather said about our profession?”

“I believe she said it was for the ‘phlegmatic,’” answered my other young aunt who read widely and remembered what she read.

Sources:

Census, directory information compiled by Paul Liepe

Death notice: “Miss Pattie Douthat Dies at Home Here”, The Bee (Danville, VA) 11 August 1930, pg. 1

I Live in Virginia; Julian R. Meade; Longmans, Green and Co., New York, NY, 1935, Chapter 7

Wow! This was so much fun to read! Thank you`

Thanks so much for this well researched, delightful article about these people who lived so long ago. I wish I had known them all!