In the early part of the twentieth century, drug store remedies abounded. One had only to go to the local drug store (there was practically one on every corner) and pick up some elixir or liniment, and all that ailed you might be cured.

In the early part of the twentieth century, drug store remedies abounded. One had only to go to the local drug store (there was practically one on every corner) and pick up some elixir or liniment, and all that ailed you might be cured.

Maybe.

Prior to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 medicine manufacturers were not required to provide their patrons with a list of ingredients. These secret recipes were mixed from a combination of ingredients that might include home-grown herbs, high proof alcohol, and a myriad of other mysterious ingredients that they were not obligated to disclose.

In the prohibition era, especially, such concoctions were often purchased for their alcohol content alone. Products like Konjola made their makers millions simply by providing a legal means of consuming alcohol when it was otherwise illegal.

Alcohol was hardly the most dangerous ingredient. “Doping” was a big issue in the 1930’s when it was discovered that narcotics were being added to many elixirs and concoctions. Highly addictive substances like cocaine brought the customers coming back…so long as it didn’t kill them first.

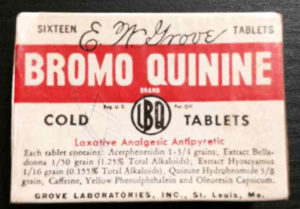

Products like Bromo Quinine Cold Tablets contained quinine hybromide. These and other bromide products caused bromism, a dangerous condition that caused many deaths from the beginning of its use in the 1880’s until products using it were taken off the market in the 1970’s.

Products like Bromo Quinine Cold Tablets contained quinine hybromide. These and other bromide products caused bromism, a dangerous condition that caused many deaths from the beginning of its use in the 1880’s until products using it were taken off the market in the 1970’s.

Other ingredients included creosote and sulfides, which were considered highly effective in “curing” coughs and colds. Creosote was also used in skin liniments. In small doses it does have a soothing effect, but used in too high a concentration it can cause burning and irritation, stomach pains, respiratory problems, and kidney and liver damage. In recent years, creosote has been found to be a carcinogen. Stop the cough, bring on the cancer!

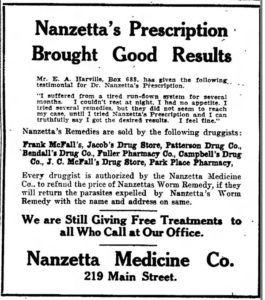

For medicine men like Dr. Nanzetta, the prohibition brought enough customers that he and his ilk could suspend their town-to-town peddling in favor of a storefront, which, because of the demand for alcohol based products, they could now afford. Medicine men often sold their wares through druggists, escaping licensure laws and other qualifications. Local advertisements of the day included the names of Frank McFall’s, Jacob’s Drug Store, Patterson Drug Co., Bendall’s Drug Col, Fuller Pharmacy Col, Campbell’s Drug Co., J.C. McFall’s Drug Store, and Park Place Pharmacy.