Much of what follows is taken from the book, Five Sisters: The Langornes of Virginia by James Fox, a descendant of Phyllis Langhorne, younger sister of Nancy and Irene, and is a much more in-depth look at the family than we had space to discuss in the article on their Danville home, the Langhorne House, now a museum located at 117 Broad Street.

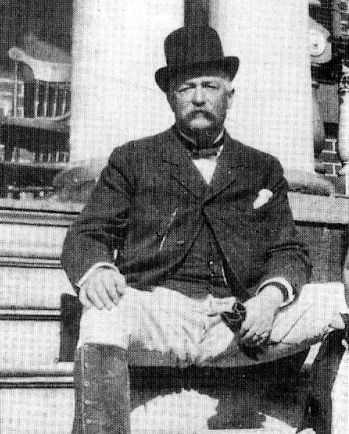

The story of the Langhornes of Danville begins with Chiswell Dabney Langhorne, the family patriarch and father of the future Lady Astor and Irene Gibson famed for bringing Charles Dana Gibson’s illustrated model to life.

Chiswell, known by his friends as “Chillie” (his name would have been pronounced Shilly Lang-un back in the day) was born in 1843 into a family of Southern landed gentry, “the old squirearchy” as some called it. The family had a farm and flour mill near Lynchburg where stood “one of the largest houses outside of town, overlooking the James River”. By the time he was old enough to hold a rifle, that wealth, like all the old families of the South during the war, had evaporated. If he did not inherit the land or money he might otherwise have been entitled to, he at least had inherited the self-assuredness of his class. According to James Fox in Five Sisters, The Langhornes of Virginia, Chillie “radiated confidence through is birth-given assumption that he could do anything better than anyone else, despite twenty-five years back and forth from the breadline.” To balance those qualities, he was also described by his sister, Liz Lewis, as “kind and tremendously honest”.

The Langhornes were natives of Lynchburg. At the age of 18, at the opening of the Civil War, Chillie enlisted along with his father. Although his obituary of February 15, 1919 states that he served with distinction during the last years of the war, historic records indicate that he was “absent sick” for several weeks in July and August of 1861 while he suffered from “feverish boils” before being discharged with disability in October of that year. It is said he suffered from survivors’ guilt in the years that followed, particularly after Gettysburg when so many of his kin and comrades were lost.

It was not long after his discharge that Chillie came to Danville “in the last grim days of the Confederacy” according to Fox. What brought him here is not entirely certain. It surely was not for the booming tobacco market or the riches that might be found here, as Danville was a fairly desolate place in the years during the war. Perhaps it was Miss Nancy Witcher Keene who lured him here. Nancy, according to Fox, “was a beauty of delicate but striking classical looks, sharply blue eyes and a trim figure, who would have been a Danville belle but she never had her moment. Nancy, according to Fox, “was a beauty of delicate but striking classical looks, sharply blue eyes and a trim figure, who would have been a Danville belle but she never had her moment.” Perhaps it was the gentleman in Chillie and an innate need born of his admiration of her, perhaps, to protect her and her family during times of deprivation and danger.

Chillie, then 21, married the 16 year old Nancy, later known as “Nanaire” in December of 1864, four months before the war’s end. In the early years of their marriage, the family lived in a tented camp in Danville (possibly the prison hospital) where Nanaire worked as a nurse. After the war, Chillie found employment as a desk clerk before exploring his talents in organizing workforces, particularly in the growing railroad industry. The family moved around, from Danville to Richmond to Campbell County where they were living in 1870, as Chillie looked for any work that could be got to support the quickly growing family.

Chillie, then 21, married the 16 year old Nancy, later known as “Nanaire” in December of 1864, four months before the war’s end. In the early years of their marriage, the family lived in a tented camp in Danville (possibly the prison hospital) where Nanaire worked as a nurse. After the war, Chillie found employment as a desk clerk before exploring his talents in organizing workforces, particularly in the growing railroad industry. The family moved around, from Danville to Richmond to Campbell County where they were living in 1870, as Chillie looked for any work that could be got to support the quickly growing family.

In 1865 the couple’s first child was born. Sarah appears in the 1870 census but disappears after that, and so it may be supposed she died in infancy. Two years later, in 1867, Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne was born. In 1869, Elisha Keene (known simply as Keene) was born, and then followed three children , John in 1870, Mary in 1871, and Chiswell Jr. in 1872 who all died in early childhood. By the time Irene was born in 1873, Elizabeth was old enough to help her mother to care for her siblings.

It was probably during this time, with the Danville tobacco market in post-war recovery, that Chillie tried his hand as an auctioneer. The work hardly paid, but Chillie was good at it. According to Fox, Mr. Langhorne had “become a legend as a tobacco auctioneer, turning the business of selling two bales a minute into a comedy routine, pulling the crowds to his act.” Fox had the opportunity of interviewing Mrs. Beatty Moore, a childhood friend of the Langhorne daughters, who illuminated Mr. Langhorne’s legendary auctioneering career further. “…there was a big rock in Danville on which he stood. It was known as Langhorne’s Rock. Mr. Langhorne was remarkable man and he was a most amusing man, and somebody always had a story on Mr. Langhorne. He wasn’t a tobacco auctioneer for very long but he was a cracking good one.”

In December of 1873, Nanaire purchased, through her trustee, Mr. W.P. Graham, “60 ft on Main Street” from the estate of Thomas B. Doe. For more on the house, please read the article dedicated to the Langhorne House, 117 Broad Street.  The house that existed in Chillie’s time looks nothing like it does today. Fox describes the house as an “overcrowded four-room bungalow”, which, according to newspapers at the time of its restoration in the mid 1980s, was then one story with a steeply pitched roof and livable attic space that may have been added sometime after the Langhorne’s purchase of it. It was here Chillie and Nanaire lived with Chillie’s brother, Tom, his sister, Liz, and soon his parents, too.

The house that existed in Chillie’s time looks nothing like it does today. Fox describes the house as an “overcrowded four-room bungalow”, which, according to newspapers at the time of its restoration in the mid 1980s, was then one story with a steeply pitched roof and livable attic space that may have been added sometime after the Langhorne’s purchase of it. It was here Chillie and Nanaire lived with Chillie’s brother, Tom, his sister, Liz, and soon his parents, too.

Harry was the first to be borne in the Danville home, followed by Nancy in 1879, Phyllis in 1880, and William Henry in 1882. By then, Chillie had entered into the railroad business, but he was not immediately successful. Sometime around 1888 he got his first break, and the family moved to Richmond where they bought the finest and largest house they had yet owned. Two years later, on the heels of Irene’s social debut when she had been “unveiled as a Belle at White Sulfer Springs—changing from a schoolgirl into a local figure of royalty—Chille Langhorne finally went bust”. The house was packed up in preparation to be sold, and Nanaire prepared to retreat with her children, including infant Nora, to her cousin’s house in the countryside, while Chilly prepared to take lodgings as a boarder in Richmond until he could find work. Just as suddenly as their fortunes had disappeared, they were once again made. One day, as Nanaire was making her final preparations to leave their Grace Street home, and with trunks and boxes packed, the younger children, including Nancy and Phyllis (ages eleven and ten) sitting atop the trunks ready and waiting to depart with their teary-eyed mother, when Chillie burst through the door and cried, “Hold everything. Hold everything!”

That day, General Henry T. Douglas, a friend of Chillie’s who, understanding his talent for working with employees and keeping them happy—or at least content during a time where improvements in working conditions were slow, particularly for the formerly enslaved. Douglas was having trouble managing the space between his Northern investors who wanted better results and his employees who kept leaving to find better conditions. Chillie knew how to manage that space and to manage the men who worked for him in a way that created a cooperative spirit of progress during a time rife with labor riots. From that moment, the Langhorne’s rise was mercurial.

That day, General Henry T. Douglas, a friend of Chillie’s who, understanding his talent for working with employees and keeping them happy—or at least content during a time where improvements in working conditions were slow, particularly for the formerly enslaved. Douglas was having trouble managing the space between his Northern investors who wanted better results and his employees who kept leaving to find better conditions. Chillie knew how to manage that space and to manage the men who worked for him in a way that created a cooperative spirit of progress during a time rife with labor riots. From that moment, the Langhorne’s rise was mercurial.

In 1892, Mr. Langhorne purchased “Mirador” a large estate near Charlottesville where, without opposition and away from the public eye (except for when he gave his frequent and lavish parties) he could reestablish some semblance of the old South from which he had come and which he felt himself a part of still.

In total, the Chillie and Nanaire had eleven children, though, as we already mentioned, she lost three of them in quick succession as infants.

Of the eight children who survived infancy:

Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne was born on the 18th of March 1867 in Danville before their house on the corner of Main and Broad streets was built. Elizabeth was a child of the Civil War and in her heart was therefore embedded a hatred of the North. The idea of securing her wealth by marrying a Yankee had not occurred to her. The family were still poor and struggling when she married fellow Virginian Thomas Moncure Perkins of Richmond. Wed in 1886, Elizabeth had almost a decade to spend watching, and with some resentment, the flock of men who travelled south by train to court her younger and extraordinarily attractive sister Irene, and, as an elder sister who had helped to raise her younger siblings, she felt she had some say in it, too. Even to her mother, Lizzie “seemed to come,” as Fox puts it, “from a different, older generation. She had a sense of correctness, a severe side to her, that belonged with the elaborate funeral conventions of Richmond.” She had much to say regarding her younger sisters’ deportment and the way they behaved. She considered her mother “unsuitably young and gay”. She had a temper and was confrontational. “She fought Chillie as if he were her own husband.”

Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne was born on the 18th of March 1867 in Danville before their house on the corner of Main and Broad streets was built. Elizabeth was a child of the Civil War and in her heart was therefore embedded a hatred of the North. The idea of securing her wealth by marrying a Yankee had not occurred to her. The family were still poor and struggling when she married fellow Virginian Thomas Moncure Perkins of Richmond. Wed in 1886, Elizabeth had almost a decade to spend watching, and with some resentment, the flock of men who travelled south by train to court her younger and extraordinarily attractive sister Irene, and, as an elder sister who had helped to raise her younger siblings, she felt she had some say in it, too. Even to her mother, Lizzie “seemed to come,” as Fox puts it, “from a different, older generation. She had a sense of correctness, a severe side to her, that belonged with the elaborate funeral conventions of Richmond.” She had much to say regarding her younger sisters’ deportment and the way they behaved. She considered her mother “unsuitably young and gay”. She had a temper and was confrontational. “She fought Chillie as if he were her own husband.”

Though Elizabeth was born in Danville, she did not grow up here but moved with the family as they chased prosperity. She spent much of her developing years in Richmond and remained there after her marriage. “This was the Richmond of Reconstruction, of black veiled war widows, drunken husbands, winter mud and summer dust, of obsession with genealogy and, above all, with talk.” Fox further describes “Lizzie” as a … “strict pioneer figure of stern elegance and puritan disapproval.” Though she is depicted as having a dour demeanor, she was considered an exceptional beauty in her day. At the time of her daughter’s marriage in 1916, the papers went out of their way to express their admiration for her (perhaps in part because of the fame of her sisters) and especially for her beauty even over the bride to be. Lizzie and her husband had four children, the eldest of whom, Thomas Moncure, Jr. died at about thirteen months of age of influenza.

Lizzie and her husband’s marriage was not a particularly happy one, but Lizzie, the most religious and conservative of them all, thought divorce a sin. When her sister, Nancy, divorced her first husband, Lizzie stormed about the house declaring all the Langhornes together were disgraced and threw down her blinds in protestation. She would stick her marriage out, but by 1908, she found herself desperate to escape both Richmond and her husband. She decided to separate herself, though not legally. Her lawyers had advised her to wait it out, as Moncure was ill with heart disease and his drinking would only hurry things along. With this advice Lizzie went off to Paris and spent fortunes, racking up debts that had to be repaid by Nancy and by her father. She was a Langhorne, and she deserved all the spoils her sisters enjoyed, despite her not having had the opportunity her sisters had been given to marry a wealthy English nobleman.

Lizzie and her husband’s marriage was not a particularly happy one, but Lizzie, the most religious and conservative of them all, thought divorce a sin. When her sister, Nancy, divorced her first husband, Lizzie stormed about the house declaring all the Langhornes together were disgraced and threw down her blinds in protestation. She would stick her marriage out, but by 1908, she found herself desperate to escape both Richmond and her husband. She decided to separate herself, though not legally. Her lawyers had advised her to wait it out, as Moncure was ill with heart disease and his drinking would only hurry things along. With this advice Lizzie went off to Paris and spent fortunes, racking up debts that had to be repaid by Nancy and by her father. She was a Langhorne, and she deserved all the spoils her sisters enjoyed, despite her not having had the opportunity her sisters had been given to marry a wealthy English nobleman.

On the 25th of March 1914, Moncure died after a long struggle with heart and liver problems. Despite her long and seemingly desperate efforts to be rid of him, Lizzie was devastated. A few days later she was summoned to New York where she might seek solace with her sister, Irene. She died suddenly after a shopping trip, succumbing to apoplexy just thirteen days after her husband’s death.

Elisha Keene Langhorne was born Jan 28, 1869 in Danville. “Keene” as he was called made his fortune in railroad as his father before him had done. He married Sadie Reynolds in 1904 and the couple settled in Richmond. Keene was not a healthy man and struggle with tuberculosis for some time, probably even before his marriage. On the 25th of December 1916, at the age of 47, feeling particularly unwell, he set out for Arizona in hopes that the climate would benefit him. He made it as far as Birmingham, Alabama where he died two days after leaving him.

Elisha Keene Langhorne was born Jan 28, 1869 in Danville. “Keene” as he was called made his fortune in railroad as his father before him had done. He married Sadie Reynolds in 1904 and the couple settled in Richmond. Keene was not a healthy man and struggle with tuberculosis for some time, probably even before his marriage. On the 25th of December 1916, at the age of 47, feeling particularly unwell, he set out for Arizona in hopes that the climate would benefit him. He made it as far as Birmingham, Alabama where he died two days after leaving him.

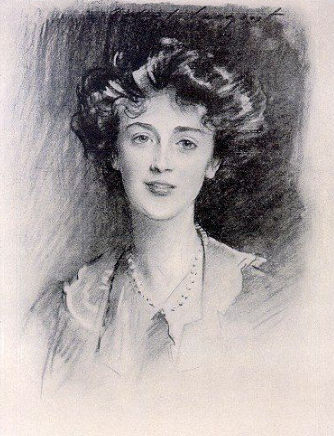

After the deaths of three infant children, two boys and one girl, Irene was born in Danville on the 7th of June 1873, sixteen years after her elder sister. Irene was the subject of great admiration long before she met the artist and illustrator Charles Dana Gibson. By the time Irene was old enough to socialize, her father had obtained some of his wealth and a good deal of his fame and reputation. In a day when socializing and being seen at the “right” places was inseparable to gaining fortune and influence, the family took long summer vacations at the Grand Central Hotel at White Sulphur Springs in West Virginia. Here wealthy southern families brought their sons and daughters in hopes of making a good match. At Mirador, too, there were parties and many opportunities for wealthy Southern sons to socialize with the charming and beautiful Irene Langhorne. But the sons of Northerners came, too, both to “The White” as the West Virginia resort was called and to Mirador. One such Northerner by the name of Ward McAllister, seeing Irene as the rising star she was, invited the young woman to lead the grand march (the opening dance) at the Patriarch’s Ball, one of New York City’s most prestigious events which took place annually at Delmonico’s. Irene was the first southerner ever to lead the ball, and it was this event that thrust her onto the national social scene. Soon after, she was invited to open the Philadelphia Assembly, and then to be the Mardi Gras queen in New Orleans.

After the deaths of three infant children, two boys and one girl, Irene was born in Danville on the 7th of June 1873, sixteen years after her elder sister. Irene was the subject of great admiration long before she met the artist and illustrator Charles Dana Gibson. By the time Irene was old enough to socialize, her father had obtained some of his wealth and a good deal of his fame and reputation. In a day when socializing and being seen at the “right” places was inseparable to gaining fortune and influence, the family took long summer vacations at the Grand Central Hotel at White Sulphur Springs in West Virginia. Here wealthy southern families brought their sons and daughters in hopes of making a good match. At Mirador, too, there were parties and many opportunities for wealthy Southern sons to socialize with the charming and beautiful Irene Langhorne. But the sons of Northerners came, too, both to “The White” as the West Virginia resort was called and to Mirador. One such Northerner by the name of Ward McAllister, seeing Irene as the rising star she was, invited the young woman to lead the grand march (the opening dance) at the Patriarch’s Ball, one of New York City’s most prestigious events which took place annually at Delmonico’s. Irene was the first southerner ever to lead the ball, and it was this event that thrust her onto the national social scene. Soon after, she was invited to open the Philadelphia Assembly, and then to be the Mardi Gras queen in New Orleans.

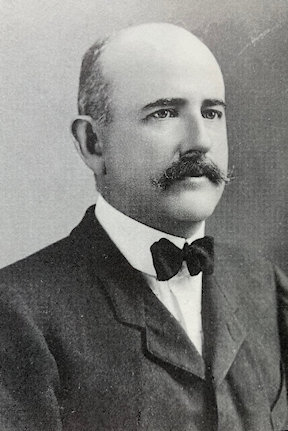

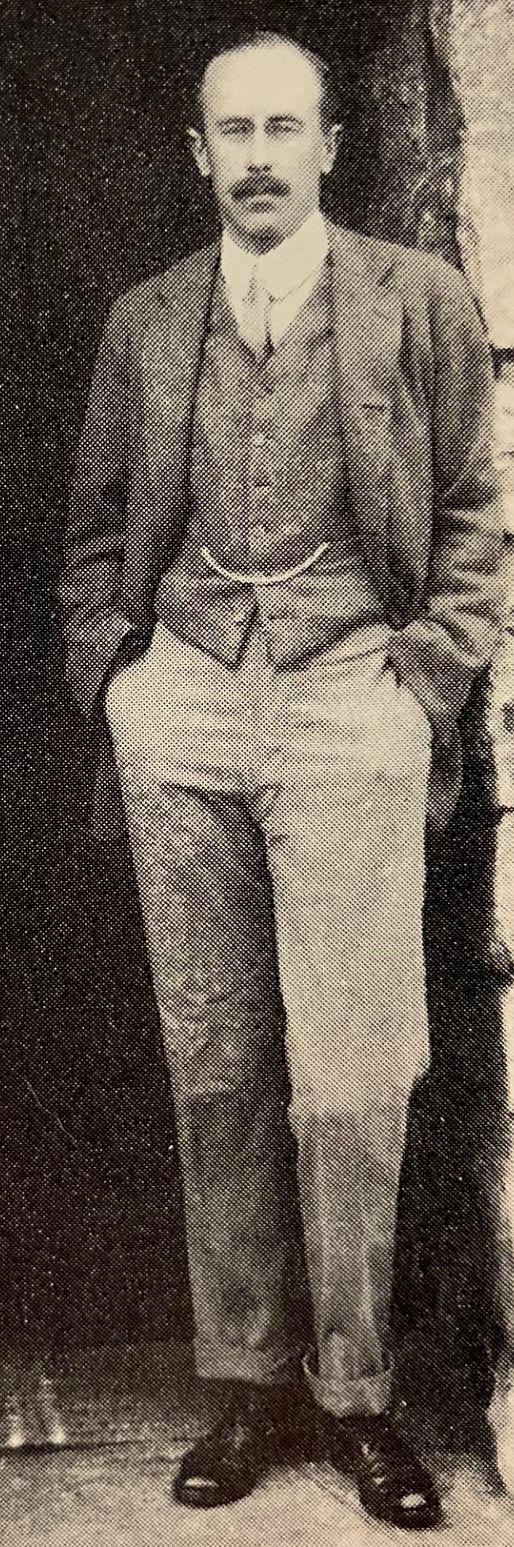

In the summer of 1894, while at a dinner held in her honor at Delmonico’s she was seated at a table with the novelist Richard Harding Davis and his good friend, the already famous Massachusetts born artist and illustrator Charles Dana Gibson. The Gibson Girl of Dana’s creation was a regular in Harper’s Weekly, Scribner’s and Colliers magazines. Irene seemed to him (and to all who saw her thereafter) as the embodiment of that, until then, imaginary figure of the feminine ideal.

“Irene, passive and golden, was the image of what men expected from women of that era—unintellectual, chaste but flirtatious, stately an amusing—the eternal belle…”

A year later, Gibson traveled to Mirador to ask for Irene’s hand. Chillie was unmoved by the man’s petition. Still chafing from the humiliation of the North’s conquest over the South, Mr. Langhorne had yet to relinquish the resentment he felt. Not only that, but Irene could have anyone, and he saw no reason why she should settle for a “Yankee sign painter,” as he then referred to him. But Mr. Gibson was not without charm of his own, and, in time, he won over Mr. Langhorne. The couple married on the 7th of November 1905 at Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond. Historians looking back on the event, including Fox himself, deemed their marriage as a “symbolic end to the Civil War” and it drew a curtain upon the golden age of the “southern Belle”. Irene was the first of the belles to come out in the North, and she was the last as well. According to Fox, “Their marriage in Richmond was an affair of American royalty and was seen as another symbolic end to the north-south hostilities.” It was also, of all her sisters, the happiest and most successful.

Irene used her fame and influence for good. Even in her seventies, Irene was “an object of wonder”, still beautiful, still charming, still full of energy. Throughout her married life, she made appearances for the benefit of a public who still wished to be entranced by her, and through her popularity, she raised a great deal of money for charities like the Child Planning and Adoption Committee (for which she sat as chairman), the State Charities Association, and she even founded the New York branch of the Southern Women’s Educational Alliance.

Irene was described by her nephew, David Astor, as having “an Edwardian queenliness about her” and that she “gave a lovely gentle atmosphere, a sense of well being and ease.”

Except for a stint in England just after the turn of the century, the Gibsons spent most of their marriage between homes in New York City and on an Island off the coast of Maine. They had two children, Irene, whom they called “Babs” and Langhorne who was known simply as “Lang”. Irene died in 1956, twelve years after her husband, at the age of 83.

Except for a stint in England just after the turn of the century, the Gibsons spent most of their marriage between homes in New York City and on an Island off the coast of Maine. They had two children, Irene, whom they called “Babs” and Langhorne who was known simply as “Lang”. Irene died in 1956, twelve years after her husband, at the age of 83.

A little over a year after Irene’s birth, Harry was born. He arrived on the 24th of October 1874 in Danville and may have been the first to have been born in the house that then stood on the corner of Main and Broad streets. He married Genevieve Gordon Peyton in 1903. Like Keene, he too contracted tuberculosis, and it seems he did so before his marriage. His obituary of 13 November 1907 in the Washington Post reads “Mr. Langhorne had been in delicate health for several years past, and, when it was found that it was some form of lung trouble, his father purchased for him a home on the top of the Blue Ridge Mountains near Greenwood, where he had resided for the past four years. Harry left behind no children. At the time of the 1900 census he was living at Mirador with his parents and younger siblings. Under the field for “occupation” it simply reads “at home”. He may not have been well enough to have secured a career or occupation, and his family was certainly wealthy enough, by then, to support and care for him.

Next came Nancy, born May 19, 1879 in the Main Street home in Danville.

We’ve written about Nancy Langhorne who, as Lady Astor, became the first woman every to become a member of the British Parliament, but the details of her domestic life are perhaps as interesting, if not more interesting, than her public one.

We’ve written about Nancy Langhorne who, as Lady Astor, became the first woman every to become a member of the British Parliament, but the details of her domestic life are perhaps as interesting, if not more interesting, than her public one.

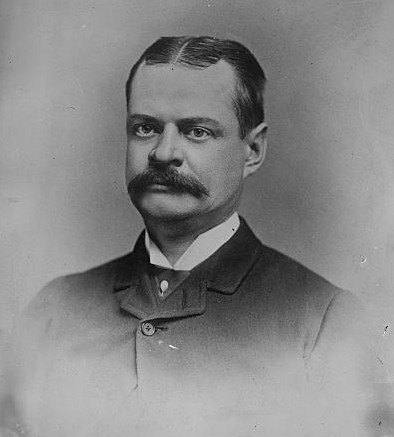

Nancy, who had some boyish tendencies and a relationship with romance that, though she was a belle to rival Irene, seemed destined to aim her toward spinsterhood, was sent to finishing school in New York. It was there she met her first husband, Robert Gould Shaw, who, unlike Nancy’s other suitors, behaved as he was supposed to (according to her standards), by falling madly in love with her at first sight and determining she simply had to be his wife. “Shaw, in his mid-twenties, was a good-looking playboy, who had been on the Harvard polo team in 1890, whose friends knew that he kept a mistress and whose father, Quincy Adams Shaw, was, by Boston standards, an extremely rich man.” [Fox]

Because Nancy was not officially “out” yet, the engagement of “Irene Gibson’s” sister seemed to the public an impetuous one. A few months into the engagement, Nancy began to agree. She had never been in love with Shaw, though she tried to imagine otherwise, and broke off the engagement. She was persuaded, however, (mostly by her mother who missed the red flags and by his mother whom Nancy truly admired) to reconsider, and, after a fifteen months’ engagement (during which time Nancy became increasingly familiar with Shaw’s dissipations) the couple were married on the 27th of October 1897 in the drawing room at Mirador (not a scandalous thing here or in England as some “historians” like to claim).

After a disastrous honeymoon that scholars have interpreted as either chaste or traumatic, Nancy begged Shaw to return her to Mirador. But separation and divorce were not imaginable, and Nancy, however daunted, returned to Shaw with the intention of sticking it out. She fled home several times, and on more than one occasion was commanded by her husband to leave, before she found herself pregnant with their first and only child, Robert Gould Shaw, II, who was born in 1898. Nancy did not remember conceiving but did claim, some years later, that she remembered Shaw coming into her bedroom one night with a chloroform-soaked sponge.

As a means of surviving the marriage, Nancy turned her full attention upon her son, but by 1900, she had had enough and at last went to her father-in-law for help. It had been Nancy’s responsibility to “get Bob right” (he was a desperate alcoholic, abusive, and unfaithful) but the task was beyond her. Her father-in-law’s advice was to go back home, give it six months, he’d turn his son around, but “Bob” as he was called, had returned back to his mistress on the heels of his honeymoon. By 1901 her family and even the Archdeacon Neve (she and all the Langhorne family were devotedly religious) were advising her to get a divorce, but divorce at the turn of the century would mean scandal and social ruination. As a divorcee, however young and beautiful, she could never hope to marry again. She did, however, agree to sign a deed of separation in 1901. Over the next two years, she grew increasingly warm to the idea of a divorce even while the separation proved, after all, to make her the outcast she feared.

Single but still married, Nancy returned to Mirador to contemplate her next move. Being neither married nor unmarried, she found she had few prospects to look forward to, but she was not to sit in limbo for long. She soon received a letter from her father-in-law in which she was informed that Bob had “married” his mistress. Bob was wanted for bigamy and the only solution, or so her father-in-law claimed, was for Nancy to seek a divorce and for it to be granted quickly and quietly to avoid all scandal—for Bob. But that meant Nancy would have to assume the responsibility of the divorce, claiming an “incompatibility of temperament”. Nancy wasn’t having it. The only conscionable grounds for divorce in her opinion was adultery, and only for that reason would she agree. The Shaws fought her, but with her father’s support, she sued for divorce on the grounds of adultery and won, receiving a settlement for her considerable trouble. The scandal was no small affair, after all, but it was not she who had been in the wrong, and so she had stood her ground.

Single but still married, Nancy returned to Mirador to contemplate her next move. Being neither married nor unmarried, she found she had few prospects to look forward to, but she was not to sit in limbo for long. She soon received a letter from her father-in-law in which she was informed that Bob had “married” his mistress. Bob was wanted for bigamy and the only solution, or so her father-in-law claimed, was for Nancy to seek a divorce and for it to be granted quickly and quietly to avoid all scandal—for Bob. But that meant Nancy would have to assume the responsibility of the divorce, claiming an “incompatibility of temperament”. Nancy wasn’t having it. The only conscionable grounds for divorce in her opinion was adultery, and only for that reason would she agree. The Shaws fought her, but with her father’s support, she sued for divorce on the grounds of adultery and won, receiving a settlement for her considerable trouble. The scandal was no small affair, after all, but it was not she who had been in the wrong, and so she had stood her ground.

In October of 1903, Nanaire suffered a sudden stroke and died. According to Fox, Nancy “suffered a depression that made her ill and wretched for months; she felt a ‘sorrow such as I had never known or imagined. The light went out of my life’.” [Fox]

In the wake of her mother’s death, Nancy tried to step in as substitute in the upkeep of Mirador, but she did not have the temperament for it, nor the patience with the staff or with Chillie. By great effort, her father at last persuaded her to make another visit to England in 1904 so that she could visit her sister Irene and benefit by a change of scenery and improving (and advantageous) company. She took her sister, Phyllis, with her along and their children and settled themselves for the time in London. Phyllis was soon called back to Long Island by her own dissolute husband, but Nancy made the most of the trip, returning to Mirador with a broken heart and five unanswered proposals. In 1905 she returned to England, this time with her father accompanying her. On boat from New York to Liverpool, Waldorf Astor was a passenger. It was hardly happenstance. The two had not yet met, but he had fallen in love with her by reputation and had determined already that he would marry her. Upon hearing of her plans to return to England, he kept track of the passenger lists and placed himself strategically. He wrote a letter soon after departure and requested an opportunity to meet her. Seasickness, however, prevented Nancy from making good on her agreement for several days. While he waited for her to be ready to receive him, he spent his time ingratiating himself with Chillie.

Waldorf’s family was the richest in America when they left New York for Rome in 1882. Waldorf was then just three years old. When his father’s ambassadorship ended, the family was to return to New York, but Waldorf’s father (who rarely spoke to him and was considered “insanely unsociable” even with his own wife and children) sent the boy to England. He was nine years old and would never live in the U.S. again. That same year, in 1888, his father joined him, renouncing his U.S. citizenship and becoming a naturalized Englishman. From that time forward, he maintained a single-eyed aim at obtaining a peerage, buying Cliveden, a Restoration Baroque House situated on a wooded hill that looked down on the on the Thames. He later bought Hever Castle in Kent, the home of Anne Boleyn as well as several hotels and newspapers.

In spite of his upbringing, or perhaps because of it (he was raised by a tutor and a governess whom he adored) Waldorf was a kind man—in stark opposition to his father’s cruelty. Fox describes him as a man of “saintly disposition, but no scintillation, no great joy.” He adored Nancy. She did not return his adoration, but “she sensed in his single-minded determination a rocklike indestructible force that could contain her, and beneath this he had independent, highly unorthodox views for his class and time and high ideals. He wanted to make up for his father’s lack of public spirit, and he took the view that his millions would not belong to him, but be held in trust for the improvement of the world about him.”

The couple were married on May 3, 1906 at All Souls’ Church, Langham Place, in secret. Nancy, uncertain she would be allowed to marry in a church as a divorcee, had written the Bishop who, considering her circumstances, had agreed on the condition that the ceremony be attended only by family and that there would be no publicity, but they had carried out their courtship and engagement so quietly (Waldorf was an innately quiet and private man) that no one knew of it but their most intimate family and friends. The date itself had been kept quite secret until the last moment. The couple honeymooned in Cortina, and, as a wedding present, William Waldorf Sr., made a gift of a large house called Cliveden in the county of Berkshire (northwest of London).

The Astor’s marriage was not perfect; they were often engaged, particularly in the early years, in battles of wills and stalemates of purpose and intention, but overall, Nancy considered him “a wonder as a man for all men are trying” and “a man in 10,000.” She did grow to love him. She certainly felt safe with him, and money was not an issue—he shared it with her quite freely—but he would never “rise to the status of ‘soul’s companion’ ” as Fox puts it. Nancy, so far away from America, made it a certainty that her first husband would never see his child. Waldorf, if not legally then in every other way, adopted him, and though they had five children of their own, “Bobbie” was treated (by Nancy’s design and insistence) as a favorite. Waldorf indulged her.

Waldorf was not a healthy man. He suffered from angina and from tuberculosis (though he didn’t know it until about 1910), conditions he carried with him into the marriage and for the remainder of his life. Nancy had her own ailments, mostly of energy. There were days she could not get out of bed, and yet she was, on her good days, extraordinarily energetic. She was of a passionate nature, and felt the importance of helping the less fortunate (in letters written to her sister she confided her feelings of unworthiness in having found herself so advantageously circumstanced). Wealthy Americans, whatever their histories, far from being shunned, were “popular, needed, and welcome in [English] society.” [Fox] And she, aided by Irene’s fame and her own charm and initiative, was immensely popular from the moment of her marriage to Waldorf, and, in certain circles, even before it.

In order to help her husband find some purpose, something to live for, she pushed him toward politics. A conservative “by loyalty”, Waldorf Astor was a traditional Tory (if traditionally means “by tradition” and not in “a traditional sense” and yet their views regarding labor and women’s rights were quite liberal. They sided enthusiastically with the “War on Poverty” and supported the “People’s Budget” of 1909. In the election of 1910, Waldorf was presented as a candidate for Plymouth. Nancy went to visit the people of and took their plight to heart. They bought a house, the finest in the town, and moved there “as if Waldorf’s eventual election was a foregone conclusion.” Of course he did win, though in the second election rather than the first. Anticipating their move to London, the couple leased a palace in London in St. James’s Square.

Nancy was a woman of contradictions. From the moment she joined the Astor clan she felt as if she did not fit in. The social demands exhausted her. She would go out or entertain at Cliveden and then find herself bedridden for the next few days following, and yet she loved to be around people, particularly those whom she found interesting. Among her intimates were many of the political stars of the day as well as writers, poets, religious leaders and military statesmen (and their wives). And while she was deeply compassionate and charitable to the world at large, she loved very few people intimately, and was demonstrative with that affection to even fewer, her husband, perhaps, included. She was also known to be bitterly jealous of the happiness of others, particularly her sister Irene whose marriage was a happy one, and, eventually, of Phyllis, whose second marriage was a surprising success (even to Phyllis herself).

In 1914, Nancy became a convert to the Christian Science movement, which she credited with curing whatever weakness of energy that kept her from entertaining and socializing and stumping for her husband as much as she required or wished to do. That year the first world war started, and Cliveden was converted, at great personal expense, into a hospital for the wounded, in which both Nancy and her sister Phyllis worked as nurses.

The Astor marriage was happiest during the time of their mutual and united service to the people of Plymouth, and so it came as a bitter disappointment when, on New Year’s Day 1916, Waldorf’s father summoned his son to him and upon his arrival announced that he had accepted a barony (in exchange for his many years’ financial investment in the country’s politics and economy), a pronouncement that meant the eventual end of Waldorf’s political career, since no one holding a peerage could sit in Parliament. The incident left Waldorf and his father almost estranged. They had given no hint of Waldorf, Sr.’s impending investiture until that day.

In October of 1919, Waldorf’s father died suddenly of a heart attack. Waldorf became Viscount Astor, ending his career in the House of Commons, which was not only a loss to Waldorf and, by extension, Nancy, but to many of their constituency. The Astor’s private wealth provided for Plymouth’s social security in such a way that the local Conservatives made the decision to put Nancy’s name in to stand in Waldorf’s place while he worked to legally unencumber himself from the peerage he did not want. This was not some great push for feminism but rather a stopgap in order to preserve the hard work the Astors had done for the people who had voted for him. Nancy was not well informed in politics, and she had many erroneous ideas which she often stated with more boldness than they deserved, but she was, at least to the outside observer, fearless, and she was clever and quick on her feet and could provide the last word in almost any argument (even if it was far afield from the point at hand). After a tireless campaign where she set herself up among the poorest of Plymouth’s residents and, though at first unpopular with them simply by point of fact of being a nominal Tory, she won the hearts of locals and, eventually the seat. While she was not well-informed, she was humble enough to take advice from those who were, establishing her own council, mostly though not entirely of women, for whose causes and by whose strategies she ferociously fought. She was not popular within Parliament and was treated so consistently harshly that other women, later elected to Parliament, could not bear to sit in chambers if she was not there, and many have famously wondered how she bore it all. On one occasion, Nancy confronted Winston Churchill and asked him why he was so hostile toward her. His reply: “Because I find a woman’s intrusion into the House of Commons as embarrassing as if she burst into my bathroom when I had nothing with which to defend myself, not even a sponge.” Of course she was famous for her witty rebuttals. “Winston, you’re not handsome enough to have worries of that kind.” But the point was, she was not wanted there, not by her fellow MP’s, and they let her know it and scarcely let up for the entirety of her political career.

In 1936, as a result of a suggestion made by Phyllis, the sisters met at Mirador for what would be their last reunion. It could have been a quiet and intimate affair, but the excuse of the marriage of Buck’s valet, Clinton Harris, offered the opportunity for a community event that brough crowds, “both black and white”, to the house. Despite all the excitement, Nancy, who, in England, proudly proclaimed herself a Virginian whose roots in Southern poverty made her uniquely qualified to understand and help the poor of Plymouth (and it did—no one else could have done for her constituents what Nancy had done) refused to receive any uninvited guests. When she had come in 1922 to visit family and to serve as an emissary between London and Richmond (and by extension Washington, D.C.) she had been beset by requests for her attendance to every and any function imaginable, including a visit to Danville. Back in Virginia, every distant relative who could lay claim Nancy as kin crawled out of the woodwork to make the most of the connection, , this included distant cousin Harry Ficklen of Danville fame who, upon Nancy’s return visit to Danville, made a long speech about his beloved cousin (to her great embarrassment). This time she simply instructed the Mirador servants to announce that she was not at home. Her sisters later lamented this change in her. “I feel Nannie is now a complete alien in Virginia,” wrote Phyllis of the event, “I really can’t get over how completely removed she is from the spirit of this place .”

Months later, in January of 1937, Phyllis, Nancy’s best friend in all the world and the only person she loved her whole life (except for her son Bobbie) died of influenza. Nancy’s life was forever changed, once again, and so did her temperament. In the years that followed her sister’s death, Nancy remained just as biting and reproachful, but she lost the wit and charm that took the sting out of her barbs. It was as if she lost all patience with the world and everyone in it. Even her politics took a stingier tone. She said what she thought, as usual, but without the grace and sense of charity she had used to possess. She spoke more readily, too, and without any thought or care that she might cause offense. The filter was gone, and with it a sense of proportion. This, combined with an incoming scandal, ended her political career.

In the early days of the Hitler’s rise, it was not clear he would be the dictator he became, and many of the politicians of the day, including those who were known as regulars at Cliveden’s social events (a distinction enjoyed by a widely varied group of people) were willing to champion any leader who could bring stability to Germany’s faltering economy. Because of this, and partly out of sheer meanness, a newspaper reporter wishing to do Nancy injury, wrote an article about those who had once sided with the man who, by 1943, had proved himself to be a fascist tyrant of diabolical proportions. The reporter dubbed the group, “The Cliveden Set”, demolishing in a single stroke, Nancy’s career as MP, though she did not immediately recognize it as the end. With the false slander of the paper, and Nancy’s changing temperament, she was discouraged from running again in 1943. While she had no real sense of what the public thought of her, her family did. When Waldorf refused to support her run for another election, and with her entire family trying to reason with her, assuring her it was a certain loss, and wishing to save her from herself and any further abuse, she at last realized it was over. “[T]he effect was tragic and volcanic.” She spent the days that followed “walking up and down the terrace at Cliveden, tears streaming down her eyes.”

Without politics to aim her venom at, she turned it upon Waldorf. He moved out of the house in 1945, but Nancy’s attacks continued via post. He never ceased to express his love to her and his regret that he had disappointed her, and she never ceased to remind him of his betrayal, not until he died in 1952. In his last years, he did return to Cliveden, feeling it would be wrong to die anywhere else, though he never gave his reasons for returning. Having converted (though it’s debatable how thoroughly) to Christian Science, such talk was forbidden.

Nancy, after Waldorf’s death, alienated herself further. Her sisters refused to see her, and her children were afraid of her. Their wives, jealous lest they should make her sons happier than she had been able to do, were especial targets for attack. After four of the five marriages failed, however, she turned around and befriended her ex-daughters-in-law in typical Nancy Astor fashion. The only person who could stand her in these years was Bobbie who, struggling with his homosexuality, had been imprisoned twice (the last time in a mental institution). The two kept up their barbs and jabs almost, it seems, out of a sense of tradition until he, too, found it too much.

Nancy spent the last months of her life living with her daughter, Wissie. By then her temperament had taken another extreme turn. Her mind, slipping from her, she imagined herself back in Virginia, a young woman once again. “I was a very welcome visitor,” her son David said, regarding that time. “She was happy, light and charming and in a holiday mood. She treated me as an equal. It was a complete transformation, and it was delightful. She passed away the 2nd of May 1964, one day before her 58th wedding anniversary.

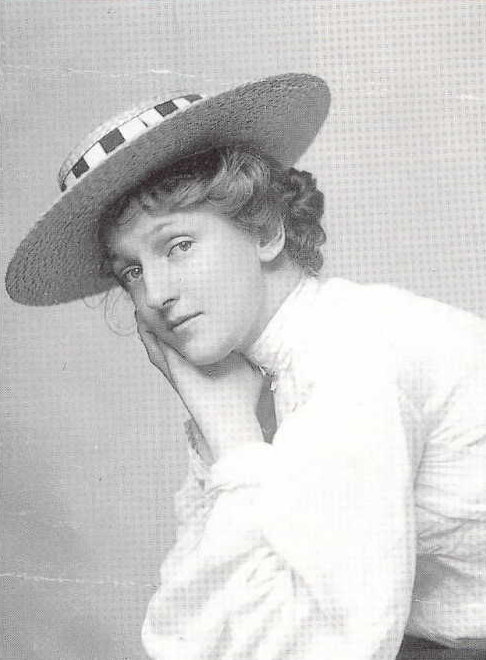

Phyllis was born just eighteen months after her sister Nancy, and the two were uncommonly close. It was to Phyllis Nancy wrote in the early years of her second marriage, confiding in her younger sister “the panic she felt having married into the Astor clan. ” Fox continues, “[Nancy] loved [Phyllis] with such a passionate longing that at times it seemed as if Nancy’s other attachments were an exhausting duty and challenge.

Phyllis was born just eighteen months after her sister Nancy, and the two were uncommonly close. It was to Phyllis Nancy wrote in the early years of her second marriage, confiding in her younger sister “the panic she felt having married into the Astor clan. ” Fox continues, “[Nancy] loved [Phyllis] with such a passionate longing that at times it seemed as if Nancy’s other attachments were an exhausting duty and challenge.

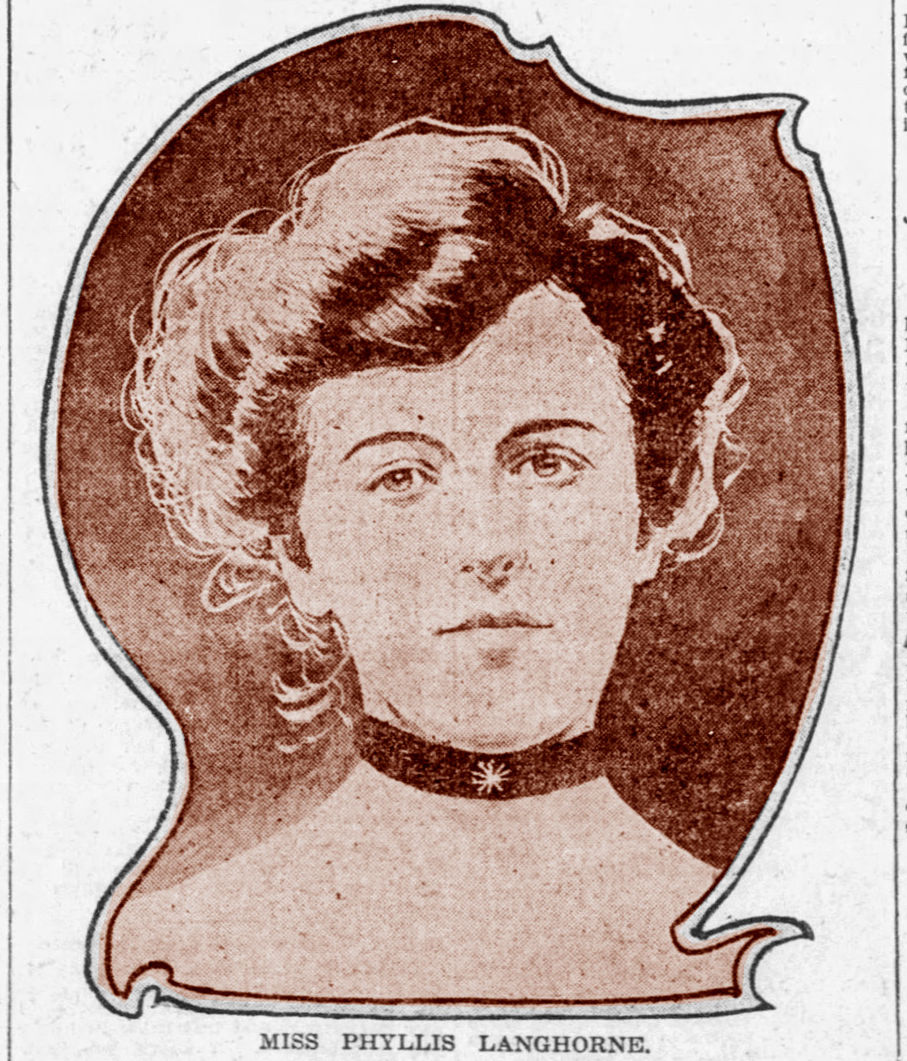

Born in Danville on the 15th of November 1880, Phyllis, according to Fox, “was the sister who had the deepest emotional effect on those around her” and that was especially true of the men of her acquaintance. “After Irene’s success,” Fox adds, the younger sisters, “began to exercise what their mother called ‘the right of every Langhorne daughter to become a belle’.”

Phyllis is described in Fox’s book as “[f]eminine, sympathetic, there was a luminous quality to her beauty, a melancholy in her nature, a minor key as her sisters called it and a streak of introversion so foreign to her father and her siblings. She radiated some mixture of love and goodness along with the connecting Langhorne gaiety. She was the most popular within her family except with her father, who disliked her reticence and her need for solitude and liked to watch the tears swell ‘diamonds’ in her eyes when he made her cry.”

Phyllis, like Nancy, was sent to New York to attend finishing school. As Nancy had been snapped up by Shaw almost at the same moment she had almost been considered eligible, Phyllis quickly “become the replacement Langhorne for 1900, effortlessly pushing aside the many other southern beauties who had now invaded northern society.” [Fox]

At the same polo field in Newport where Nancy had met Robert Gould Shaw four years earlier, Phyllis met Reggie Brooks. Reggie was the only male heir of his parents wealth (both his father’s new money and his mother’s old). Like Shaw, Reggie had been to Harvard, he played polo, he was handsome, and he was a budding alcoholic. Unlike Nancy and her soon-to-be ex-husband, however, Phyllis fell in love with him, hard and instantly. Phyllis was a great horsewoman and hunter, and it was that sport which elicited from Reggie an invitation to his estate in Aiken, South Carolina, which, like all his father’s properties, was a gathering place for the wealthy and socially influential. The Aiken property was considered the winter hunting headquarters. Here Phyllis met his family, winning approval from them and from Reggie’s close friends who took to the sporting and athletic young woman with enthusiasm.

Phyllis’s engagement announcement which ran in The Boston Globe on 16 Aug 1901 describes her with all the glowing remarks worthy of the ideal woman in the Gibson Girl age:

Another engagement of much interest to society has been announced here. It is that of Miss Phyllis Langhorne, daughter of C.D. Langhorne of Greenwood, Va. and Reginald Brooks, only son of Mr. and Mrs. H. Mortimer Brooks, who own a fine villa on the Newport cliffs.

Miss Langhorne is a very charming girl, petite and graceful. She has decided athletic tendencies and is one of the best cross country riders. She is also an expert whip and a clever golfer. Miss Langhorne also plays a strong game of lawn tennis, and in the tournament of mixed doubles recently played at the Casino she and Marion Wright of Philadelphia made a very creditable record.

Miss Langhorne is a sister of Mrs. Robert G. Shaw 2d of Boston, where she has many acquaintances and is very popular.

Mr. Brooks is a noted yachtsman. He owns a 30-footer and also sails on the Constitution in all her races. His mother was a daughter of late Elias Higgins, who made millions in carpet manufacturing. Mr. Brooks will someday have great wealth at his disposal.

Miss Langhorne passed the winter at Aiken, where she was one of the women who rode astride. No date for the wedding has yet been announced.

The couple were married on the 14th of November 1901 before 400 guests and amidst the warmest congratulations of all her friends and family … all but one. Nancy, perhaps seeing in Reggie a too similar resemblance to Bob, feared her sister had made a grave mistake. From what we know of Nancy, however, it could just as easily have been jealousy.

Phyllis and Reggie had three children together. Reginald Langhorne Brooks, known as “Pete” was born in 1902 on Long Island, and it was shortly after his birth that Phyllis began to see that her husband was not all she had at first esteemed him to be. She was desperately lonely, secluded in a home rented for them by his parents who had promised to buy or build them a house of their own. She longed for Mirador, but Reggie would not go with her and, therefore, discouraged her from going, on the off chance she should meet someone more interesting than he. He was not wrong to fear such a thing, as it turned out.

By 1906, Reggie was showing his true colors, and though Phyllis was a long way from throwing in the towel, neither was she as dutifully obedient to his jealous whims as she once was. In 1907, she went to England to visit Nancy (then married a year to Waldorf) and to take part in the New Years’ hunting. She stayed until April. Nancy was nearly despondent when Phyllis left, as much because she loved her sister like no one else in her life, but because she knew (because she had lived it) how miserable her sister was. Nancy assured her that Waldorf would support her financially if Phyllis decided to leave her husband. She still believed her divorce should only be conducted as a result of Reggie’s infidelity, but she did not want Phyllis feeling as if her financial independence on her husband’s family should be a discouragement to fighting for her freedom from someone who ill-treated her.

As Phyllis’s marriage deteriorated, she needed her sister’s company more and more. Reggie at last agreed to accompany her to England in 1907, where they stayed for four months, while Reggie complained the whole time. As Fox put it, she was “gradually attaching herself to Nancy’s English life,” and she was doing it with some success. “Nancy didn’t discourage the admirers who were circling around her sister,” Fox writes, and it was public knowledge that her marriage was failing. Phyllis’s letters swing from dejected and lonesome hopelessness to a desire, when Reggie’s moods improved (he seems to have suffered from severe depression that was made worse in cold weather) to receive his attention. The result was, that, at the same time she was assembling a list of potential second husbands (intentionally or unintentionally–Nancy remained opposed to divorce), she became pregnant with her second child. Jacki did not survive, however, and died suddenly of an intestinal blockage. His condition lasted two days while she sat at his bedside and watched him struggle in pain and then slip away from her. Phyllis was despondent. Reggie turned further inward.

Chillie, lonely at Mirador, and wishing to do his part toward securing his daughter’s happiness, purchased a much smaller home near Mirador which he called “The Misfit” and gave Phyllis the house and 500 acres. Chillie hoped that, by adopting the life a landowner he might take up farming and thereby improve his mood and temperament (and perhaps lay off the drink), and do it at a distance from which Chillie could watch over them.

The couple and their two children, Peter and David (known as Winkie) spent a fortune at Mirador reviving the gardens, digging wells to install indoor plumbing, and adding a pool and other improvements, Reggie was soon bored and consequently found excuses to keep himself away. His absences made it possible for Phyllis to carry on a sort of affair, though it was one more of imagination than of any actually sexual or even physical liaison.

It was during Phyllis’s 1907 trip to England, that she met the young Grenadier Guards officer, Captain Henry Douglas Pennant, while riding at Melton Mowbray. It was purely a friendship at first, but by 1910, he was openly declaring his adoration. After that first meeting in 1907, she saw him again in 1908. In 1909, when he was nearly mauled to death by a tiger in Nairobi, Phyllis confessed to Nancy that she had found herself in “a little harmless fling”. Nancy did not approve of Henry, but she did feel it expedient to help her sister realize how much happier she would be with almost anyone but Reggie, and so, just at first, she might almost have been said to encourage it. At least she invited him several times to Cliveden.

In 1910, “the captain” as the sisters referred to him, visited Phyllis at Mirador. By then Phyllis had given birth to her third son. Upon his return home, he made Phyllis a beneficiary of his will. It was a small income, but it was a gesture he gladly made to help an unhappily married woman whom he very much adored. It was also meant as a slight to his own family who would never have approved of her for a myriad of reasons.

In 1911 Henry managed to visit Mirador twice, but these were hurried visits conducted out of sight of Reggie (who was always away) and Chillie who was now living nearby at The Misfit, close enough to keep an eye on things as had been his intention all along.

At Christmas in 1911, Phyllis (accompanied by Reggie) went once more to England to spend a few months with her sister. She appeared looking “thin and nervous”. Nancy, who hated to see her sister wasting away in misery, began to openly encourage the divorce. Nancy was certain that Reggie’s frequent absences, both at home at Mirador and here in England where he frequented Mayfair, were evidence of his infidelity. She wanted to put a private detective on him, but Phyllis was opposed to divorcing on the grounds of adultery because she feared the scandal it would cause her children. Reggie soon after, and perhaps getting a sense of Phyllis’s desperation, made another effort at sobriety, which, at least temporarily, put a hold on Phyllis’s developing plans to leave him. In his sobriety, however, she convinced him to agree to an amicable separation, but as legal residents of New York, the separation had to continue for three years, during which time she could not produce evidence against him regarding any suspicions of adultery, but Nancy held out hope that after a year or two, he would find his own reasons to end the marriage. The separation also meant that Phyllis had to be extra cautious regarding her interactions with the captain which were relegated to letters delivered via a slow and unreliable international post.

Though Nancy wanted very much to see her sister free of her husband, she saw the flaws in the captain and wished to influence her sister away from him. For her own benefit, as well as Phyllis’s, Nancy began to collect about her a group of “bright young men”. Among these were the authors Henry James, G.K. Chesterton, and Rudyard Kipling, all of whom became regulars at Cliveden. Also included were a group of young diplomats known as The Kindergarten, who had advised the British government on a number of diplomatic missions. Among these was Bob Brand, a kind, intelligent, and somewhat awkward young man whom Nancy grew to admire very much and considered to be a good alternative to the wayward Reggie.

Bob, upon meeting Phyllis, fell instantly in love. For the next three years, Phyllis would conduct a rivalry between “the Captain” and Bob Brand. Phyllis, in her heart, preferred Henry, of whom she had made a sort of romantic hero. Bob was stable, boring, but a good and reliable friend, and she insisted he must not consider her as anything other, even though she gave him every encouragement, by her actions, by the confidences she shared with him, by the counsel and company she sought from him. Phyllis kept each gentleman abreast of her dealings with the other, maintaining their jealousy, and, for a while, it seemed a race to convince her which would make for her a better second husband after her divorce from Reggie, which had been set for August of 1915.

Bob, upon meeting Phyllis, fell instantly in love. For the next three years, Phyllis would conduct a rivalry between “the Captain” and Bob Brand. Phyllis, in her heart, preferred Henry, of whom she had made a sort of romantic hero. Bob was stable, boring, but a good and reliable friend, and she insisted he must not consider her as anything other, even though she gave him every encouragement, by her actions, by the confidences she shared with him, by the counsel and company she sought from him. Phyllis kept each gentleman abreast of her dealings with the other, maintaining their jealousy, and, for a while, it seemed a race to convince her which would make for her a better second husband after her divorce from Reggie, which had been set for August of 1915.

Fate, however, played its own hand, and when war broke out in August of 1914, Henry rejoined the Grenadier Guards, while Bob took a desk job.

On the first of March of 1915, Henry was offered a senior staff job in the Welsh Guards which would almost immediately take him out of the trenches, but it meant a career in soldiering after the war. He was trying to find a way to support his future wife and family, but Phyllis, who seemed not to understand the peril he was in, objected to the idea. She wanted a political man, not a soldiering man, and she said so. Henry, upon receiving her letter, wrote a hasty reply of apology to Phyllis and then immediately sent another letter refusing the promotion. And then he returned to the front. Early the next morning, the captain was killed in battle, struck through the lungs by shrapnel. He died almost instantly.

The papers, which reflected society’s absolute ignorance of Phyllis’s romance with Henry, blew up with the news that she had inherited the income from Henry’s estate for the rest of her life, a mystery many were desperate to learn more about—and never did. Phyllis, unlike Nora, possessed a sense of discretion, and the only details which ever came out about it were revealed decades later (in Fox’s book) through letters written between Phyllis herself and Henry or her sister Nancy.

The papers, which reflected society’s absolute ignorance of Phyllis’s romance with Henry, blew up with the news that she had inherited the income from Henry’s estate for the rest of her life, a mystery many were desperate to learn more about—and never did. Phyllis, unlike Nora, possessed a sense of discretion, and the only details which ever came out about it were revealed decades later (in Fox’s book) through letters written between Phyllis herself and Henry or her sister Nancy.

It took Phyllis several years to come to terms with Henry’s death. In her mind they were kindred spirits, destined to be together, and then betrayed by that destiny (despite the fact that they were, in actuality, quite ill-suited for each other). She swore she would never love again.

Phyllis, leaving her sons behind (a decision that would eventually cost her her relationship with both children from her first marriage) joined Nancy at Cliveden, which had been converted into a hospital. It was there she tried to work through her grief.

Bob Brand, in the background, remained hopeful. He was patient, and waited for Nancy’s cues before he once again tried his hand. Phyllis told him she could not love him, would not marry him, but would be his friend if only he would stop proposing to her. All correspondence was terminated … and then resumed once more when they found themselves bereft of the friendship that had become a source of comfort to them both. This on-again-off-again battle of wills continued for some time. They would write, he would declare his love, and she would refuse to see him, only to write again a few months later. In February of 1917, she wrote and said she would understand if he chose never to write her again, but then invited him to attend a concert with her. Of course he went. And then, in March, while at Cliveden, she asked him to come to her room. He arrived there, nervous but hopeful. She told him she had given it much thought and she did wish to marry again and that it might as well be him, and so, if he would still have her, she would agree to marry him.

They were married ten days later.

While Phyllis had firmly believed (and had even warned Bob) that she would be a disappointment as a wife who could never love him as he loved her, she actually found herself pleasantly surprised by how happy she was with him, and as time went on found herself very much in love with him, to Nancy’s resentment (even though it was she who had helped them along).

Between 1910 and some time after Phyllis’s marriage, a rift developed between Phyllis and Nancy, who had, until always been as close as two sisters could be. Indeed, they were the very best of friends, but Nancy’s staunch disapproval of Henry provided a rupture that never really healed and was further widened by Nancy’s adoption of Christian Science (which Phyllis ironically had introduced her to). The rupture became irrecoverable when Nancy began airing her resentment of Phyllis’s happiness. In a letter to Irene in 1922, Nancy wrote, “[Bob Brand] seems either weighted down with responsibility or happiness. I think and pray the former.”

Bob and Phyllis had three children, two girls, Virginia and Dina who lived into the 1990s, and Robert James Brand who died in action in Germany during World War II.

In October of 1936, the sisters returned to Mirador for their last reunion. Phyllis hoped Peter and Winkie, both of whom had returned to the United States years prior, would make an appearance. Just as Phyllis had given up hope of seeing Winkie, he arrived with his wife, walking “into the house as casually and calmly as if he had left here yesterday and been married all his life.” He treated his mother coolly, and she reciprocated. They’re relationship had ever been a difficult one, owing largely to the fact that she had sent them, quite against their wills, to boarding schools and had separated herself from them further by spending months at a time away in England during their formative years. During this time, they had written letters longing for her and she had failed to reappear, or would reappear for a short time only to disappear again in pursuit of freedom from her husband or the imagined romance of fated love, or, finally, comfort from the loss of that love. And then she had quite suddenly (or so it seemed to her children) remarried without warning.

A month later, Winkie, who had struggled much of his life with alcoholism and depression, jumped from a hotel window and died. When Winkie’s wife, Adelaide she shared the news with the family, she had described her husband’s death as an accident. Phyllis only discovered it was suicide when Irene let the secret slip in a poorly worded letter to Phyllis some weeks after the event.

In January, Phyllis, recovering from a cold, went out to ride. It was the only thing that assuaged her otherwise paralyzing grief. It was a cold day, but they, she and her daughter, had ridden hard and had gotten very hot and then very cold when the car which was meant to meet them was late. Three days later, Phyllis was diagnosed with pneumonia. She died on the 20th of January, 1937, leaving Bob Brand in a state of devastation. He had only ever loved one woman and had waited years upon years to have her, too, and now, an atheist, he found himself desperate for any real evidence that there was permanence to the human spirit. If, after all his trials, if, after all his happiness, there was nothing to look forward to, no chance of ever seeing her again, what was the point? It was a question that haunted him the rest of his life.

He died in 1963, having survived his wife by 26 years, and with his daughters nearby.

William Henry, known as “Buck”, was a cadet at the Virginia Military Institute who spent most of his time there “playing craps, riding horses, dating girls, and failing his first-year exams. He was growing up a country boy, full of ‘yee-haw’ humor and high spirits. When asked by a newspaperman if he was related to the Langhorne sisters, he said, ‘Hell, I’m one of ’em’.”

In 1919, Buck was the only Langhorne child who had remained in Virginia. That year he was elected to the Virginia state legislature. According to his sister Phyllis, though Buck was thirty-five at this time, “he was really about 3”. He was playful, jovial, and restless. Though he was married and had several children, he was rarely at home. When he wasn’t campaigning for a political position he was unqualified for (Nancy lamented that he had won a position in state government when their aunt Liz Lewis, a suffragette and highly educated, didn’t even have the vote) or out on one of his “sleepless hillbilly trips that lasted days at a time” chasing moonshine and who knows what else. Having, like his brothers, contracted tuberculosis, when he was home, he stayed in an adjoining bungalow, in quarantine from his wife and children. He was known from Richmond to Lynchburg as a friendly face and a man so sociable that his horse, upon seeing a passerby, knew to move to the side of the road and stop so that his rider could conduct a conversation.

In 1919, Buck was the only Langhorne child who had remained in Virginia. That year he was elected to the Virginia state legislature. According to his sister Phyllis, though Buck was thirty-five at this time, “he was really about 3”. He was playful, jovial, and restless. Though he was married and had several children, he was rarely at home. When he wasn’t campaigning for a political position he was unqualified for (Nancy lamented that he had won a position in state government when their aunt Liz Lewis, a suffragette and highly educated, didn’t even have the vote) or out on one of his “sleepless hillbilly trips that lasted days at a time” chasing moonshine and who knows what else. Having, like his brothers, contracted tuberculosis, when he was home, he stayed in an adjoining bungalow, in quarantine from his wife and children. He was known from Richmond to Lynchburg as a friendly face and a man so sociable that his horse, upon seeing a passerby, knew to move to the side of the road and stop so that his rider could conduct a conversation.

By descripti0n, Buck “had a long face, a large, loose mouth, freckled skin, light blue eyes, and talked in a country Virginian dialect that was often indistinguishable from the accents of his black farmworkers.” The Langhornes were known to treat like family those whom they hired to help them run their homes, including Buck who had inherited a self-running farm from his father upon his marriage to Edith Forsyth in 1907. “He just had a personality you couldn’t beat,” a friend offered to biographer James Fox regarding Buck. “[E]verybody loved him, and he had a world of friends.”

According to Fox, “Buck stood for election to the legislature for Albermarle County because he believed that public service was the duty of a country gentleman.” Like Nancy, he did not have a head for politics, but he did know how to take good advice and when to apply it.

Buck was a generous man, and, during the Great Depression, was known to load his truck up with food and deliver it around the community to those in need. Like his sisters Nancy and Irene, he, too, felt his wealth was best used to help others. He died in 1938 at the age of 55 of renal failure complicated by his many years’ struggle with tuberculosis.

“Nora the youngest,” Fox wrote, “was the eternal child. Dreamy, disorganized, and unschooled, she was talented—a brilliant mimic and inventor of skits, a talent inherited by her daughter—with a romantic smokey singing voice that she accompanied on the ukulele and guitar. She was physically the most alluring as well as the kindest hearted of them all. She was also free with her favors, unable to tell the truth and irresponsible with money. Her life punctuated with seductions and boltings, debts and broken appointments, with a charmed one until her last years, successfully devoted to making sure everyone had a good time. She said of herself that she had a ‘a heart like a hotel’. One of her old beaux added, ‘and every room was full’.”

“Nora the youngest,” Fox wrote, “was the eternal child. Dreamy, disorganized, and unschooled, she was talented—a brilliant mimic and inventor of skits, a talent inherited by her daughter—with a romantic smokey singing voice that she accompanied on the ukulele and guitar. She was physically the most alluring as well as the kindest hearted of them all. She was also free with her favors, unable to tell the truth and irresponsible with money. Her life punctuated with seductions and boltings, debts and broken appointments, with a charmed one until her last years, successfully devoted to making sure everyone had a good time. She said of herself that she had a ‘a heart like a hotel’. One of her old beaux added, ‘and every room was full’.”

Nora was born on the 14th of September 1887 in Richmond and was the only Langhorne not to have experienced Danville and the family’s destitute years. She was even too young to remember the years of feast and famine they experienced during their time in Richmond. Nora, to her own memory, had always been at Mirador … except when she was trapsing across Europe, running full speed in her sister’s footsteps to secure fame, and a husband, in England. On her first trip to Paris and England over Christmas in 1906, accompanied by a chaperone who was meant to be a protection between herself and any embarrassment she might cause, Nora made waves, but not in a good way. Nora, Fox described it, “left behind a trail of misbehavior that Nancy was continuing to discover long after her departure.” In England, she had spun a number of tales that reinvented the Langhorne history which her elder sisters had previously established. Worse, it was later discovered that she had engaged herself to a young man she had met on the ship before ever arriving in England. Of course she had forgotten all about it once she had set foot on English soil, but the gentleman had not, and in the summer of 1907, he appeared at Mirador to claim his bride. Nor was he the only victim to Nora’s unserious attitude toward love courtship. According to Fox, a string of suitors came to call that summer. Each proposed, and each was accepted. “If anybody said, ‘Will you marry me?’ Nora said, ‘Yes’,” her niece, Nancy Lancaster said many years later. “She said yes to everything and the next moment she’d forgotten she’d said it and grandfather had to keep breaking off these engagements and writing to these young men saying ‘I’m afraid my daughter doesn’t know what she’s doing’.”

Two years went by and hopes for Nora’s marriage were dwindling. Chillie, making plans to leave Mirador for The Misfit, at last gave into Nancy’s pleas to send Nora to Cliveden for a second attempt at passing her off on English society. Nora, as it happened, was not without prospects. She had engaged herself to a young Virginian from Norfolk named Baldwin Myers, of whom Chillie initially approved. Nancy, however, was certain the marriage would be a disaster. Chillie resisted, but, with the move to The Misfit on his mind, he gave in, and Nora was soon on her way to England. Between Nora’s lies, the speed with which she moved through potential suitors, and the slowness of the mail between the two countries, considerable confusion and more than one misunderstanding was had before Nora was at last engaged (and, at least to Nancy’s mind, suitably) to an English architect (and a contemporary of Waldorf’s at Eton) named Paul Phipps. Though Nancy approved of the match, she did warn Paul of Nora’s ways. He was undaunted and was determined to love her whatever her failings. They were married in April of 1909 and moved into a house rented for them by Nancy in Monteplier Square. Paul appears to have indeed been an improving influence upon Nora who seemingly had, upon her marriage to him, quite “mended her ways”. At least for a time.

Two years went by and hopes for Nora’s marriage were dwindling. Chillie, making plans to leave Mirador for The Misfit, at last gave into Nancy’s pleas to send Nora to Cliveden for a second attempt at passing her off on English society. Nora, as it happened, was not without prospects. She had engaged herself to a young Virginian from Norfolk named Baldwin Myers, of whom Chillie initially approved. Nancy, however, was certain the marriage would be a disaster. Chillie resisted, but, with the move to The Misfit on his mind, he gave in, and Nora was soon on her way to England. Between Nora’s lies, the speed with which she moved through potential suitors, and the slowness of the mail between the two countries, considerable confusion and more than one misunderstanding was had before Nora was at last engaged (and, at least to Nancy’s mind, suitably) to an English architect (and a contemporary of Waldorf’s at Eton) named Paul Phipps. Though Nancy approved of the match, she did warn Paul of Nora’s ways. He was undaunted and was determined to love her whatever her failings. They were married in April of 1909 and moved into a house rented for them by Nancy in Monteplier Square. Paul appears to have indeed been an improving influence upon Nora who seemingly had, upon her marriage to him, quite “mended her ways”. At least for a time.

Paul struggled to get work, and a year after they were married, he moved Nora and their young daughter, Joyce, to Vancouver, Canada, where, by Paul’s own admission, Nora was left “almost literally alone and has not one single friend”. In 1913, their son Tommy was born, and the family moved to New York. and then, with the outbreak of war, Paul returned to England to offer his services, even though he was too old to be called up.

Nora, returned to civilization, and now without her husband to watch over her, dived into her social life like a fish starved of water. According to Fox, “Nora’s ‘heart like a hotel’, closed for some seasons on account of her marriage and children, was now open again with light and welcome.” Her “fresh start” meant returning to her old ways, and almost immediately Paul had left, Nora met a Yale football hero named “Lefty” Flynn and engaged herself to him, abandoning her children and running off with him with no indication, and perhaps no idea, actually, of where they were going. They were at last discovered, singing for money on their way cross-country, where they were recognized. Dana Gibson went out to retrieve her and brought Nora home, embarrassed and socially ruined. Paul, of course, forgave her and hardly mentioned it. She, in turn, never forgave him for not caring that she’d tried to abandon him.

Eventually Paul was assigned a position as a musketry instructor which kept him in remote training locations, far from Nora, while Nora was summoned to Cliveden in the hopes that, keeping her under her elder sisters’ noses would keep her out of trouble (it didn’t). Nora, in Paul’s absence, participated in romances with several of the Guards officers who came and went from the hospital at Cliveden. In addition, she became a confident and a would-be chaperon turned accomplice in her nephew’s escapades. When, in 1916, Paul was declared unfit for service due to a persistent knee problem, he returned to London to work at the Admiralty but found himself mostly at Cliveden where he refused to help and aired his resentments at Nora being so much occupied in nursing. Considering Nancy supported her, and heavily, it did seem to Paul as though Nora’s volunteering was a full time occupation. Nancy congratulated herself on converting Nora to Christian Scientism and its assistance in producing a Nora ” so improved”. But once again, Nancy was mistaken.

At the end of the war, Paul and Nora moved into a small apartment in Chelsea, London, and though their letters to the sisters offered testimony of Nora’s “improving”, in fact she was deeply in debt and out of love with her husband, but determined, owing to her adherence to her newly adopted religion, to “stick to Paul”. Paul was not helping matters by demanding Nora love him as his right.

At the end of the war, Paul and Nora moved into a small apartment in Chelsea, London, and though their letters to the sisters offered testimony of Nora’s “improving”, in fact she was deeply in debt and out of love with her husband, but determined, owing to her adherence to her newly adopted religion, to “stick to Paul”. Paul was not helping matters by demanding Nora love him as his right.