The story of Langhorne House and the family whose name the once much humbler residence bears is one of contradictions. The name Langhorne, today, represents old money, opulence, international politics, and turn of the century fame, but the family’s years in Danville were anything but opulent.

The story of Langhorne House and the family whose name the once much humbler residence bears is one of contradictions. The name Langhorne, today, represents old money, opulence, international politics, and turn of the century fame, but the family’s years in Danville were anything but opulent.

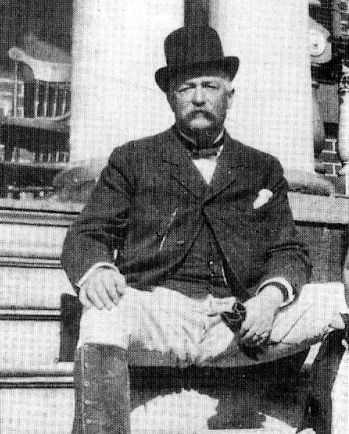

Chiswell Dabney Langhorne, known by his friends as “Chillie” (pronounced Shilly) was born in 1843 near Lynchburg into a family of Southern landed gentry, but that wealth was swept away by the ravages of domestic conflict. Chillie spent a little time in the fight but not much and was discharged in October 1919 by disability that, supposing it was not exaggerated, may have been a result of stress.

It was not long after his discharge that Chillie came to Danville, a fairly desolate place in the years during the war and after the war. Shortly after arriving here, he met the young Nancy Witcher Keen, known as “Nannie” and later “Nanaire”. The couple married in December of 1864 when Chillie was 21 and Nancy a mere 16 years old.

In the early years of their marriage, the family lived in a tented camp in Danville (possibly the prison hospital, see the link above) where Nanaire, was a nurse. After the war, Chillie worked as a desk clerk before finding employment as a tobacco auctioneer. The family moved around, from Danville to Richmond to Campbell County where they were living in 1870, as Chillie looked for any work that could be got to support the quickly growing family.

In the early years of their marriage, the family lived in a tented camp in Danville (possibly the prison hospital, see the link above) where Nanaire, was a nurse. After the war, Chillie worked as a desk clerk before finding employment as a tobacco auctioneer. The family moved around, from Danville to Richmond to Campbell County where they were living in 1870, as Chillie looked for any work that could be got to support the quickly growing family.

In 1865 their first child was born. Sarah appears in the 1870 census but disappears after that, and so it may be supposed she died shortly after. Later that year, Elisha Keene (known simply as Keene) was born, and then followed three children , John in 1870, Mary in 1871, and Chiswell Jr. in 1872 who all died in infancy. By the time Irene was born in 1873, Elizabeth was old enough to help her mother to care for her siblings.

It was probably during this time, with the Danville tobacco market in post-war recovery, that Chillie tried his hand as an auctioneer. The work hardly paid, but Chillie was good at it. According to James Fox in his book Five Sisters: The Langhornes of Virginia, Mr. Langhorne had “become a legend as a tobacco auctioneer, turning the business of selling two bales a minute into a comedy routine, pulling the crowds to his act.”

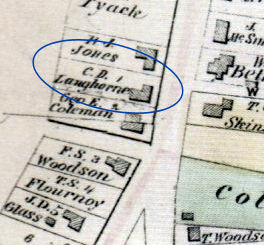

In December of 1873, Nanaire purchased, through her trustee Mr. W.P. Graham, “60 ft on Main Street” from the estate of Thomas B. Doe “in trust for the sole use and benefit of Nannie W. Langhorne during her life and at her death to be taken in fee simple by the children of the said Nannie W. Langhorne living at the death of said Nannie W. Langhorne” for the sum of $500. Thomas T. Shadrick, in a 1988 article in the Danville Register, suggested that the house was not built on the lot but moved there before the Langhorne’s bought it, though the deed mentions no preexisting structures nor does the price at $500 (which might simply be a result of Reconstruction era valuation) suggest a house was present when the Langhorne’s acquired the property. Some historical accounts attribute the acquisition of the home, whether built, existing, or moved onto the property, to Chillie’s first break in the Railroad business. It is also possible that the money was provided as a gift by Nancy’s mother who would no doubt like to see her daughter and her grandchildren nearby.

The house that existed in Chillie’s time looks nothing like it does today. “The house was a cottage about 30 feet from the street,” according to a description by Ellie Fitzgerald who, before the house was moved to its present location in the 1920s, attended school there, and who was quoted in an article published that same 1988 Danville Register article. Ms. Fitzgerald further described the house as having a “front porch (that) was the length of the house” and indicated that the schoolroom was held in the front room on the Broad Street side. Another contributor to the Register piece described the home as being “a five-room house with a hallway down the middle.” He didn’t remember seeing a stairwell. “They had to raise the roof because it used to be an A-frame roof and now it’s flat.” Mr. Shadrick further contributed his observations of the house describing that the “doors in the upstairs have the trim designs of the 1870s “while the “wood framing of the archways are old with added 1920-style cross beams.” Such details led him to believe the second-story was “either part of the original building or added shortly after it was moved on the lot before the Langhorne’s bought the place.”

The house that existed in Chillie’s time looks nothing like it does today. “The house was a cottage about 30 feet from the street,” according to a description by Ellie Fitzgerald who, before the house was moved to its present location in the 1920s, attended school there, and who was quoted in an article published that same 1988 Danville Register article. Ms. Fitzgerald further described the house as having a “front porch (that) was the length of the house” and indicated that the schoolroom was held in the front room on the Broad Street side. Another contributor to the Register piece described the home as being “a five-room house with a hallway down the middle.” He didn’t remember seeing a stairwell. “They had to raise the roof because it used to be an A-frame roof and now it’s flat.” Mr. Shadrick further contributed his observations of the house describing that the “doors in the upstairs have the trim designs of the 1870s “while the “wood framing of the archways are old with added 1920-style cross beams.” Such details led him to believe the second-story was “either part of the original building or added shortly after it was moved on the lot before the Langhorne’s bought the place.”

Fox describes the house as an “overcrowded four-room bungalow” and it was here Chillie and Nanaire lived with Chillie’s brother, Tom, his sister, Liz, and soon his parents, too. Harry was the first to be borne here, followed by Nancy in 1879, Phyllis in 1880, and William Henry in 1882. By then, Chillie had entered into the railroad business. Danville was a good place to start, since the expansion of said railroad, a result of a cache of coal having been found in the remotes of southwestern Virginia which, once mined, needed transporting to the ports of Norfolk.

Fox describes the house as an “overcrowded four-room bungalow” and it was here Chillie and Nanaire lived with Chillie’s brother, Tom, his sister, Liz, and soon his parents, too. Harry was the first to be borne here, followed by Nancy in 1879, Phyllis in 1880, and William Henry in 1882. By then, Chillie had entered into the railroad business. Danville was a good place to start, since the expansion of said railroad, a result of a cache of coal having been found in the remotes of southwestern Virginia which, once mined, needed transporting to the ports of Norfolk.

Chillie was not immediately successful, but sometime around 1888 he got his break, and the family moved to Richmond where they bought the finest and largest house they had yet owned. Two years later, on the heels of Irene’s social debut, Chillie Langhorne found himself on the brink of bankruptcy and financial ruin. That same day, or so legend has it, his fortunes were remade, and this time permanently, when he was offered a position by friend who understood Chillie’s talents with management in a time when employee relations were tense to say the least.

Four years later, in 1892, Mr. Langhorne purchased “Mirador” a large estate near Charlottesville, a home that soon and would forever after be identified as the seat of the Langhorne family.

Four years later, in 1892, Mr. Langhorne purchased “Mirador” a large estate near Charlottesville, a home that soon and would forever after be identified as the seat of the Langhorne family.

Much can and has been written about the Langhorne’s. For a full account, we suggest the fascinating book by James Fox, Five Sisters: The Langhorne’s of Virginia. Fox is a descendant of Phyllis Langhorne and through his grandfather inherited a treasure trove of letters which informed the book on the family in a way no other has been able to do. Five Sisters is a wonderful insight into the famed Langhornes of Danville. If you haven’t time for the biography, you can read a brief history, essentially a synopsis of the book, on the dedicated to the Langhorne family here. Though Nancy and Irene are still famous today, the other children are equally fascinating and were, in their day, almost as famous.

Though the Langhorne family left Danville in 1882, the family retained ownership of the home until 1909, six years after Nanaire’s death. The house did not, however, stand empty during the interim. In 1902, Miss Betty Watkins had a private school here. Prior to then, according to the 1900 Census it was the home of Joseph T. and Mary Smith and their two sons. The household included two servants.

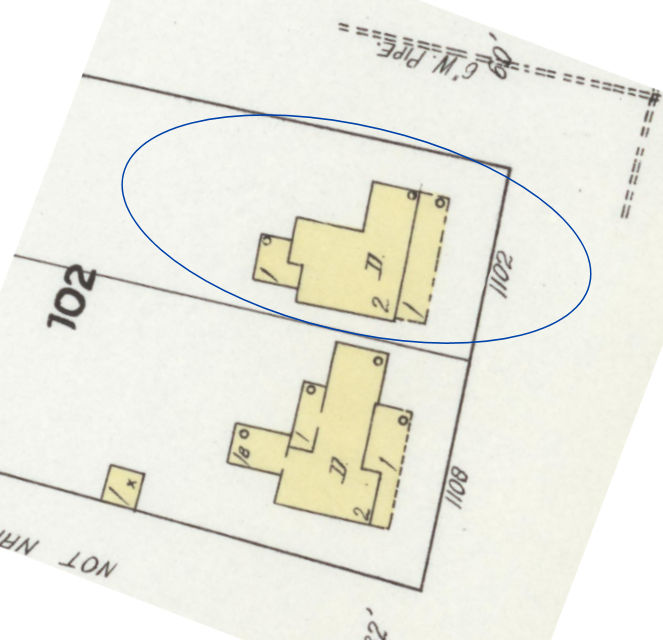

The 1909 deed of sale for the property at 1102 Main Street bears the signatures of all the living Langhorne children including Irene Gibson, Lady Astor, and Chillie himself. The house was purchased by Rice Gwynn for $6,000.

Stephen Thomas Rice Gwynn was born 19 June 1872 in Caswell, North Carolina. He started his career in tobacco in Reidsville, and later joined the American Tobacco Co and then R.J. Reynolds Tobacco, Co. He married Bertha Savage in 1942. The couple had three children, two daughters and a son, Rice Gwynn, Jr.

Judging by census records, the Gwynns lived at 1102 for the first ten or so years of their ownership of the home. In 1910 they shared the house with Bertha’s brother and his family.

In 1921, a notice appeared in the paper making the announcement that the house was “being moved bodily from its position on Main street at the intersection of Main and Broad streets, and will be taken on rollers backward down Broad Street and then turned round so that the font of the large two-story frame building will face Broad street. Once place upon new foundations it will be divided into two apartments.” Mr. Gwynn further proposes to erect a smaller and more modern dwelling on the Main Street site using part of the old foundations. According to staff at the Langhorne House Museum, the rails used to move the house back are still present in the basement. The house was not, however, “pivoted” but now presents its eastern facing side toward Broad street. A staircase was added to reach the upper floors and a room built onto the rear corner on the Broad Street side.

Almost precisely upon the completion of the project, it was learned that Lady Astor was visiting family near Richmond and was offered a last minute invitation to travel southward to visit her childhood home. Her acceptance of the invitation caused a frenzy. She was presented by A.B. Carrington and an introduction was read from the second story balcony by cousin Harry Ficklin who appears to have made the most of the event. Lady Astor was next to speak, and though, as Member of Parliament, she represented the conservative Tory Party, both she and her husband, Waldorf (whose abdication from his seat in Parliament upon his becoming 2nd Viscount, a position he in turn inherited from his father, allowed Nancy to assume) were fiercely in favor of women’s rights. She encouraged women to take part in politics and to do their utmost to promote the cause of women wherever they could and to help the poor, another passion of hers. She said little of her childhood home, only that it reminded her of her mother, for whom she was still grieving. Having left as a young girl, she claimed, it was difficult to remember. It was a diplomatic way of saying what she could not, that Danville, poor as the family had been, held few happy memories. As far as the house was concerned, it was so altered by then, she could not have recognized it even if she had held onto memories, happy or otherwise.

Irene also spoke at the event, but Nancy was the news of the day. That a Danvillian had become the first woman to take a seat in Parliament was the stuff of fairy tales, and locals celebrated her victory as their own.

The house, at the time of Lady Astor’s 1922 visit was still referred to as the “Gwynn Residence” but by 1930, they were living at 551 West Main Street. The new apartment building they proposed to build may indeed have been built upon the foundation of the old Langhorne foundations, that house having already been 30 feet from the street was now 70 feet removed from Main Street frontage. Over the years, however, the building grew and expanded so that it nearly touches the sidewalk on both sides and is actually attached physically to the Langhorne house as if they were at one time all one building. The original facade therefore lost to time and memory.

In it’s time as an apartment building, the Broad street house was “home to the famous and to the descendants of the famous”, according to a 1988 article. “In apartment No. 3,” the article goes on to explain, “for 30 years lived the descendants of Thomas Jefferson: Ellen Ruffin Featherston and her sister, Mary Blairs Harvie Ruffin.” Their nameplates, at least in 1988 when the house was salvaged from demolition and decay, were “still nailed on the trim of the outside door leading to the upstairs. The plates were painted over years ago.”

Betha Gwynn died in 1942 of Pneumonia. Rice followed eleven years later of a seven years’ battle with pancreatic cancer.

After the Gwynn’s the house stood empty for a long time. In 1987, the then Mayor Steward Anderson called the house “a derelict structure and a public health hazard and has been in disrepair for years. It’s a shame that house could not have maintained its value as a desirable residence. But what do you do when it reaches a point that it’s a blight on the neighborhood.”

The question was answered shortly thereafter when, following the Mayor’s threat of demolition, a group of Danvillians rose up to fight for the home’s salvation. the Fourth Viscount Astor, William Waldorf Astor III, grandson of Lady Astor, pledged his support. Funds were raised, but the $4,000 collected did not come close to the home’s $32,000 asking price. The demolition was set for August. In July, Stuart J. Grant, publisher of the Danville Register and The Bee purchased the house. the Lady Astor Preservation Trust was established a few weeks later, and the house was donated to the trust, which remodeled and restored the home, though it retained the upstairs apartments as a means of funding the maintenance of the house.

Today, the ground floor of the house is operated as a museum in honor of Lady Astor, the Gibson Girl, and the Langhorne family.

For more information, including hours of operation, call

Sources:

Census and Vital records found at Familysearch.org

Images and vital information, including biographical sketches found at FindaGrave.com

Death notices and other information found in the Danville Register, Danville Bee and other newspaper archives at Newspapers.com and GenealogyBank.com

Census, Directory, Newspaper, and other information compiled by Paul Liepe

Five Sisters: The Langhornes of Virginia. James Fox. Simon & Schuster, 2000