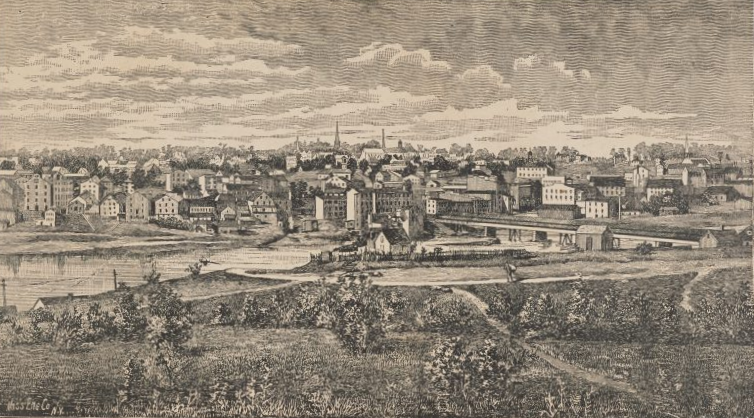

In 1860, Danville, Virginia boasted a bustling 3,500 citizens. The tobacco trade had brought a degree of prosperity the small town had scarcely dared to dream of before that time. Edward Pollock, author of the 1885 Sketch Book of Danville, described the city as “unique in its exceeding attractiveness” and as one in which its citizens were enjoying “an unparalleled period of growth and prosperity.” Besides the town’s five banks, several hotels, and thirty-some prosperous businesses, there were over a dozen tobacco warehouses. Statistics of that date suggest that as much as 46% of the town’s labor force worked in tobacco. Danville even hosted its own inspection station.

And then came the Civil War.

According to a master’s thesis published by Karen Lynn Byrne in 1993 for Virginia Polytechnic Institute, a majority of Danville’s population, including Major William T. Sutherlin and Massachusetts-born educator Levi Holbrook, were opposed to secession, preferring the preservation of the Union. Most of Danville’s tobacco went North, after all, and though some believed that secession could only make Danville more prosperous, most of its more influential citizens foresaw that the cost of war would be financially devastating.

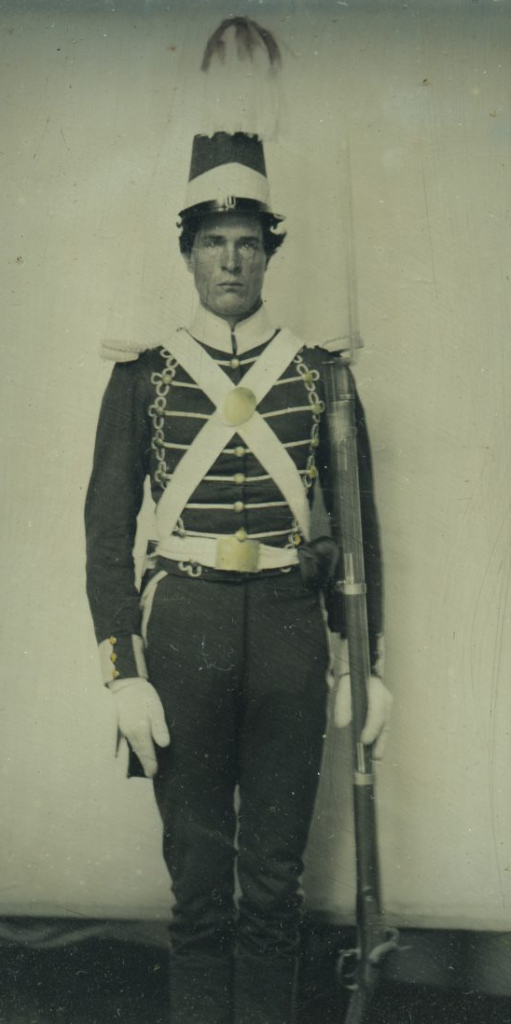

With the decision to join the Confederacy made by leaders in Richmond, Danville’s population began to experience its first losses. Almost immediately, 200 soldiers, those of the Danville Blues and Danville Grays, left for Richmond to begin training for battle. Next to depart was a battery of artillery and a troop of cavalry. Stores closed, warehouses shuttered, and factories shut down as more and more men left to do their part. The installation of an armory seemed to many of Danville’s citizens to put a target on the town’s back. Fear of a coming invasion forced Danville’s several educational institutions to close. Soon all that would be left were the old and the very young, the women, and the citizens of color. By 1863 this “unique” and “exceedingly attractive city” “presented an appearance of general desolation.”

The price of food skyrocketed. Butter, which had sold for 20¢ before the war rose to $3.00 per pound by 1863. Potatoes went from $1.37 a bushel to $6.00. And those were the prices for items that could be got. Coffee disappeared, and flour became so scarce it was auctioned off by the ounce.

As Danville’s native population dwindled, refugees—mostly women and children—from the embattled regions of Virginia, from the coast and the environs to the North, flooded into the town, swelling the population to 6,000. The lack of housing reached a crisis level when hotels and boarding houses ceased to have vacancies. Local families opened their homes to strangers so that, “every house was filled to the limit of its capacity.” These new inhabitants did not add to the labor force, and instead placed an additional burden upon the city’s waning resources.

That strain would only be made greater when, in May of 1862, the Confederacy established a military hospital in Danville on the corner of Jefferson Avenue and Loyal Street. Whether that hospital occupied a building that was standing already (that of the Danville Female Academy, perhaps) or on an empty lot nearby, it is difficult to say. Regardless, the resources such a facility required for the treatment of its sick and injured (both Confederate and Union alike) were difficult, if not impossible, to come by, and these wounded soldiers arrived in Danville more to suffer than to recuperate.

By 1863, the prisons in Richmond were full to capacity and then some. Libby prison hosted some 12,500 inmates, and the facility had depleted Richmond’s resources and left the city, the capital of the Confederacy, hobbled. More prisons were needed and quickly. Danville, situated directly on the railroad line and with several, now empty, tobacco warehouses, seemed to offer a perfect solution. And, while these empty tobacco factories in and of themselves provided a solution to the prison housing problem, there was no other reason to think of Danville as an obvious spot for the support and maintenance of large numbers of prisoners. Neither was there any system for keeping such prisons as a separate entity from the communities in which they were hastily established. The population of prisoners, prison guards, soldiers, and hospital patients was so interdependent upon the community that every need, every deprivation, every disaster experienced by the prisons and those who dwelled within them was shared by the general population.

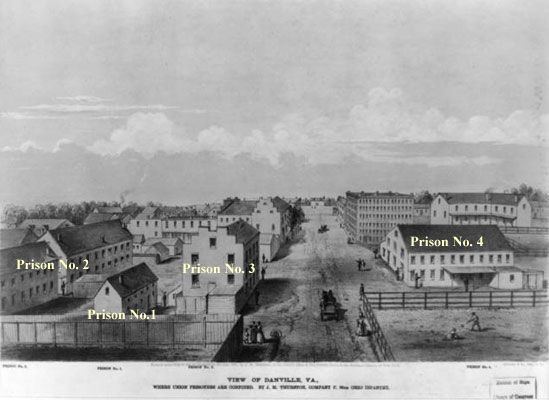

Four of the prisons were situated along Spring and Union Streets. Prison nos. 1 and 2 were connected, and it was on the ground floor of Prison 2 that the prison headquarters was located. Prison 3 was the officer’s prison. Prison No. 4 stood at the intersection of Spring and Union Streets. Prison no. 5 stood at the corner of Floyd and High Streets, while prison no. 6 still stands at the intersection of Lynn and Loyal streets.

Four of the prisons were situated along Spring and Union Streets. Prison nos. 1 and 2 were connected, and it was on the ground floor of Prison 2 that the prison headquarters was located. Prison 3 was the officer’s prison. Prison No. 4 stood at the intersection of Spring and Union Streets. Prison no. 5 stood at the corner of Floyd and High Streets, while prison no. 6 still stands at the intersection of Lynn and Loyal streets.

The buildings (except for No. 2) consisted of a ground floor or “basement” with dirt floors, and two or three upper stories. Behind each of the prisons was a small yard enclosed by a high wooden fence where the men could wash in a common water trough or spigot and relieve themselves in makeshift privies.

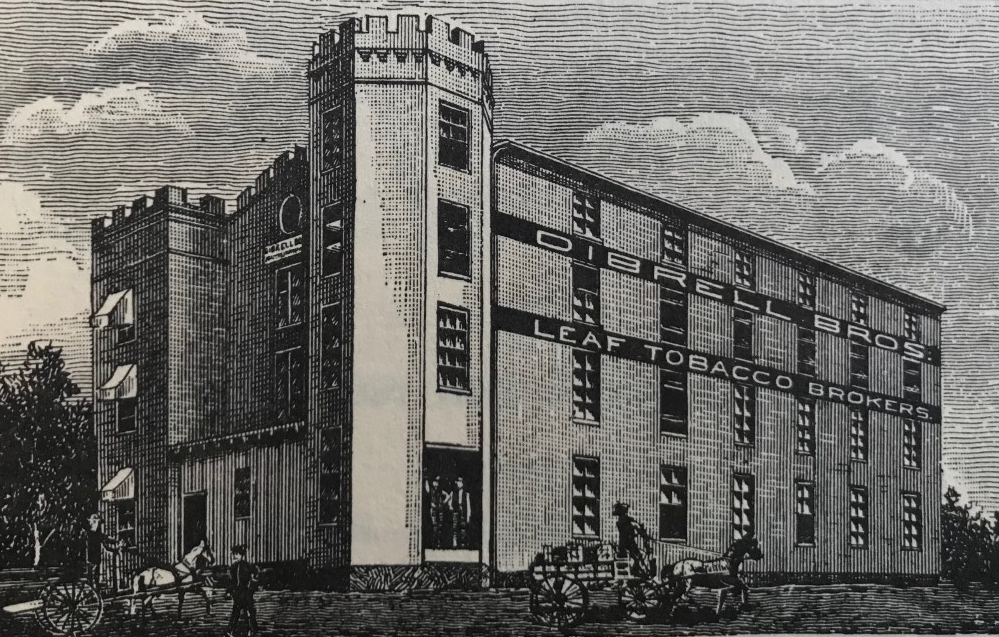

[The C.R. Thomas building (once the Dibrell Warehouse as shown in the image above) was constructed by William T. Sutherlin in 1855. It underwent major renovations in 1915. Originally a three and a half story structure, it was converted into four stories by altering the floor and ceiling heights. The turrets were removed and the windows were bricked up and relocated to match the new floor levels. The building served as a leaf tobacco factory before the war, and then again after it until 1937 at which time it functioned as a general merchandise store until the 1970’s.]

The first prisoners arrived in Danville on November 13, 1863 to find that scarcely more than the buildings themselves had been provided for their accommodations. There were no furnishings, no beds, just floors caked in tobacco debris and dirt and the four walls to enclose them. In the rare instance that a stove was provided for their comfort, no wood or coal could be found to fuel it.

The prisoners arrived in Danville by train. 200 men came each day for the next three weeks so that, by November 25th, 4,200 prisoners were installed in the town’s new prisons. Soon the population of the town would double. More than 7,000 Union prisoners were in Danville at one time, attended by their guards, medics, and other Union personnel.

A fairly colorful account of the soldier’s journey to Danville can be found in Houses of Horror by James I. Robertson, Jr. (1961). Robertson describes the journey as one which took a full twenty-four hours, “since the track was dangerously bad and the locomotives, wheezing steam and burning twice their normal amount of wood, could make barely twelve miles per hour. Each boxcar contained seventy prisoners and four guards, and the weight of the cars and their occupants often proved too much of a strain on the engines” which would have to stop and rest. The strain was also occasionally too much for the tracks themselves, which would sometimes spread apart and have to be re-spiked before the train could continue on.

Upon arrival, the men entered the buildings to find them cold and barren with little to comfort them from the cold and hunger that had accompanied them hither. Without any beds, the men had to arrange themselves on floors caked in dirt (a combination of tobacco juice and detritus and the waste of the animals which had once moved it). One group is reported to have petitioned the prison commandment to grant them a hoe in order to scrape the two-inch crust of dirt from the floors. The request was denied on the grounds that the implement might be used as a weapon in an escape plot. The men were subsequently forced to endure the filth that became a breeding paradise for rats, vermin, and disease.

The prisoners slept directly on floors caked two inches thick with dirt that had been there upon arriving, but the problem was quickly confounded simply by the necessities of living. Only a few men at a time could be let out into the yard to use the privies, and the wait times too often outlasted the prisoners’ abilities to wait—particularly once they were inevitably afflicted with the gastrointestinal issues consequent of insufficient nourishment. The men slept in rows of four, two rows with their heads to the walls and the other two with their heads to the center of the building. The former proved the more preferred position, since the half-boarded windows let in some air to lessen the stench of unbathed bodies and uncovered waste. But it also let in the cold. The men slept so closely together that cries of “spoon left” and “spoon right” were called out through the night to synchronize a unison turning in their makeshift “beds”.

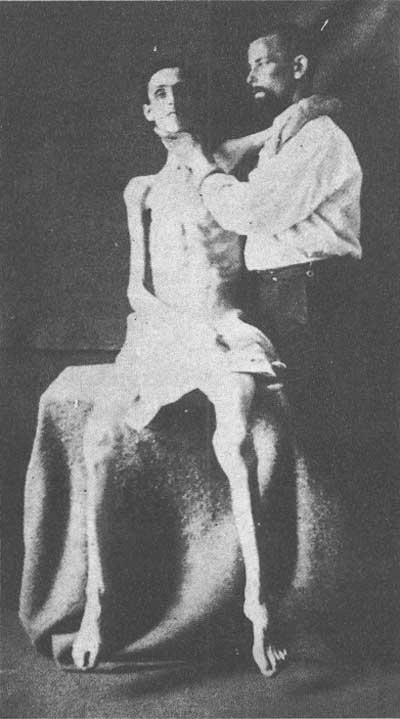

As for pastimes, the men spent hours each day delousing themselves and each other, picking fleas and chasing away the rats and mice that were readily prepared to consume the crumbs of their meager rations. Those rations were scarce, too. Men who had not eaten since their departure from Richmond would often have to wait a full two days before at last being given their first meal, a half loaf of wheat bread. They arrived rags, too, all their supplies having been sent home. Often what was left to be brought with them—their changes of clothes and necessary toiletries—were taken by the guards whose deprivations were nearly as bleak. The threat of starvation was real. So was death by cold, since the warehouses were not insulated and could not be properly heated even under the best conditions. But, with the shortage of washing and toileting facilities, and with Danville’s sewage and water treatment systems years away from being developed, the real threat was disease. With men packed so closely together, there was no escaping it when illness broke out. And it did.

In September of 1863, Richmond had suffered its first cases of smallpox. By December smallpox at the prison at Belle Isle had reached epidemic proportions. On the 9th of that month, a group of prisoners left Belle Isle for Danville, bringing the disease with. It quickly spread, and not through the prisons alone.

“More than any other event … the smallpox epidemic revealed how closely intertwined were the prisoners’ and townspeople’s lives.” Those townspeople, who had been universally empathetic to the plight of the prisoners in Danville, and who had turned out in large numbers to share what little they had in order to ease the depravity experienced by those early inmates, were quickly driven into an attitude of panic. At no time before, nor at any time after, did the citizens of Danville express hostility toward the Union captives.” With the threat of death and disease looming, however, their attitudes quickly changed. “Waste from the hospital ran down the streets … collecting in level places until the rain washed it away.” People avoided the principle streets, warned away by the sight and stench of stagnating waste. By the end of December, “the disease was raging within the limits of the corporation.” … “Vast numbers of men contracted the virus so quickly that many died in the prisons before they could receive medical attention. … As many as eighteen patients lay helplessly on the floor without medicine while no effort was made to remove them. Sometimes two or three days passed at a time before the dead were removed.”

By the end of January, 1864, the situation was so bad that the Board of Health petitioned the Secretary of War to “move the prisoners some other place, or at least outside the limits of the corporation of Danville.”

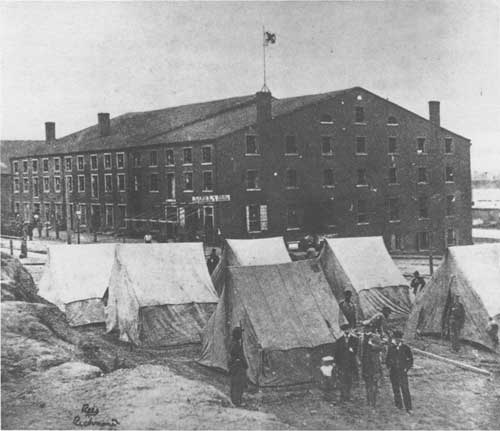

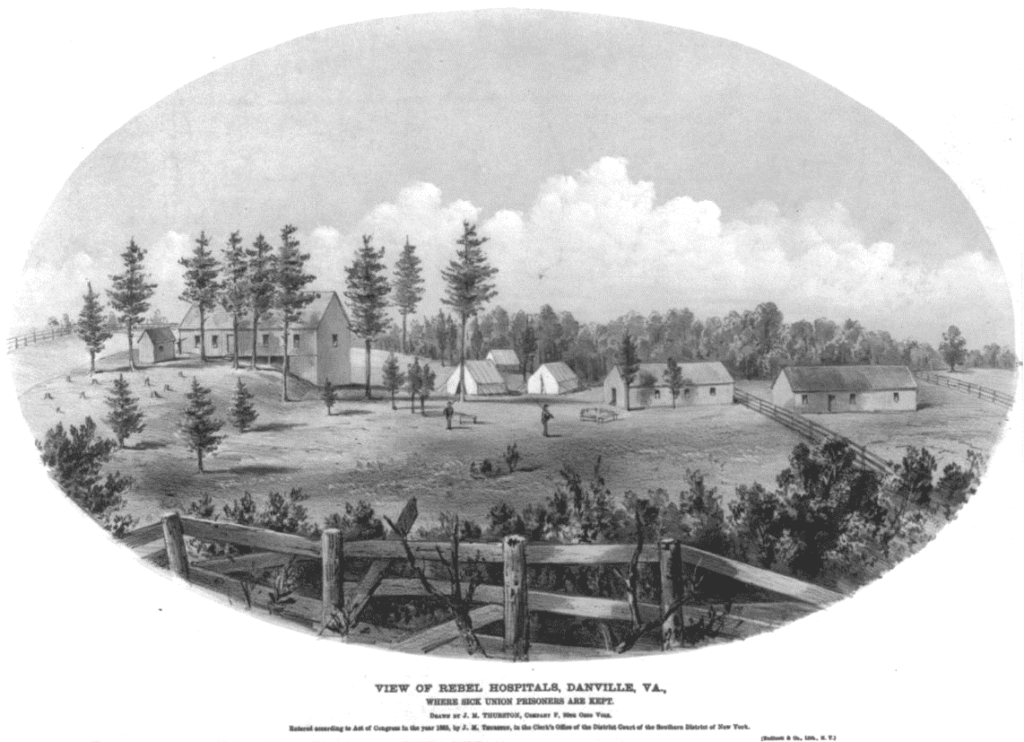

Construction began immediately, and a new facility was built on the bank of the river a mile west of town. The smallpox hospital had three wards and could house a total of 150 men. Within its camp was situated a cook house and a dead house. A row of eight tents served as quarters for convalescent prisoners and the hospital staff.

The smallpox hospital was, as it turned out, a bright spot in Danville’s prison system. Only here were there beds, clean linens, and food worth consuming. It was here, as well, where the guards were most lax, reluctant as they were to be in too close proximity to the ill. As such, the smallpox hospital camp provided an excellent opportunity of escape, and many—prisoners and staff alike—took advantage of this.

In fact, much of the hospital staff were enlistments from the prison population. There were not enough medically trained personnel by far to staff the three hospitals in Danville, and so those of the prisoners with any amount of medical training at all or who possessed sufficient capacity and willingness to learn how to nurse and care for the sick and injured, found themselves with the opportunity to escape their prison confines and find purposeful occupation. In January 1864, the entire smallpox hospital staff escaped. These were replaced, and the following month, in February, these took a similar opportunity to gain freedom. Despite it all, the Confederate medical staff had no choice but to continue to staff the small pox hospital with Federal medical personal.

It should be noted that the hospitals treated Federal and Confederate prisoners alike. Indeed, General Orders demanded that prison hospitals must be treated on equal footing as other Confederate hospitals. Federal prisoners did not suffer more in Confederate prisons, nor in the hospitals, than their Confederate counterparts. Indeed, while suffering the scourge of injury and disease, these men seemed to remember they were more alike than dissimilar. It is also true that, having prepared so little beforehand for the eventuality of a long war, neither side was truly prepared to deal with the problem of long-term prisoner detainment. If Southern war prisons were crueler than those in the North, it was merely a product of the general state of deprivation. Reports of extreme cruelty inflicted by guards upon their prisoners was not necessarily isolated but was certainly a unique product of individual guards and those who ran the prisons rather than a universal system of treatment. ‘Especially later in the war, when guards and prison officers were among those who had been previously injured or imprisoned themselves, a general degree of empathy appears to have ruled.

By March the smallpox epidemic had abated, and the citizens of Danville were once more prepared to look upon the prisoners with pity rather than malice or fear. Of all the Danvillians who assisted the prisoners, no one was more beloved than Rev. George Washington Dame (see companion post). The Episcopalian minister and head educator of the Danville Female Academy brought books and food to the prisoners. He visited the prisons daily and on Sundays conducted religious services. Prisoners who wrote about their experiences in the Danville prisons later recalled that Rev. Dame showed deep and genuine affection for the prisoners. Many wrote to him after their release to express their gratitude and considered him a true Christian.

“I feel I can never repay you, but it will be my highest ambition to do so.” one former captive wrote. Another: “Your kindness to me has been such to win my love and undying gratitude. I will remember you as one of the noblest examples of Christian men.”

After a brief stint of relative relief from deprivation and disease, darker days were once more upon the prisoners at Danville. With the arrival of autumn 1864, conditions began to deteriorate. “Extreme cold, dwindling rations, higher disease rates, and increased psychological suffering distinguished the compound’s final period of operation. Those who occupied the compound during this period endured the most lethal living conditions in the prisoners’ history.”

By winter of 1864, a general despondency had swept over the city and perhaps much of the South as well. The Confederacy was losing the war, and the total cost was not yet known. The battle dragged on. Danville’s townspeople and the prisoners alike were starving to death, and the attitude of most prisoners and those who waited word of them, their families and loved ones, knew very well how unlikely it was they would leave those prisons alive. This was especially true for the black prisoners who found themselves in Danville’s prisons. Slaves and free men alike, captured by the Union armies, were expected to fight for their freedom and the cause of the North. Consequently, upon being captured by the Confederate armies, their punishments were extremely harsh. Black prisoners were kept in prison no. 6, the coldest and most desperate of the facilities. Though a small group managed to escape the prison, the vast majority of them died. Denied treatment at the hospitals and given the poorest rations and suffering the most violent contempt by their guards, few survived more than a few weeks in the Confederate prison.

By January 1865, prison rations for everyone were nearly exhausted. Meals consisted of a three inch by four inch piece of cornbread and water to wash it down with. Such “would not more than half satisfy an ordinary man for his breakfast,” one prisoner later recalled.

The situation was dire. While overcrowding had been a major issue the summer before, disease and starvation had thinned out the prison population considerably. The prisons, which had once housed some 7,000 men, contained a mere 2,400 by November of 1864. “Of the 1,131 Federals who died in the regular hospital, 59% succumbed to disease between September 1864 and February 1865. During those six months, chronic diarrhea claimed 339 lives. Pneumonia and bronchitis also made rapid inroads among the prisoners, claiming 100 lives.”

Until spring of 1864, prisoners at least had hope of returning home via prisoner exchanges, but on April 17, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, fearing that continuing the exchange would only allow the battle to press on indefinitely, refused to release any more Confederate soldiers. Despair set in. Men who had survived starvation and disease, succumbed entirely when hope was stripped from them.

By the end of January 1865, matters were at an all time low. An inspection by Lt. Col. A.S. Cunningham resulted in a report to Gen. Grant insisting that something must be done for the prisoners languishing in the prisons. Confederate Agent of Exchange Robert Ould also petitioned Grant about this time to consider resuming exchanges. “In the interests of humanity”, Grant was persuaded to agree to a “man for man” exchange.

On February 17, 1865, a full half of Danville’s prisoners were transferred to Richmond. The remainder left the following day. As quickly as the Danville prisons had been erected, they closed again. They were temporarily reopened when 763 prisoners arrived in March from the deeper parts of the South. A month later, they, too, were gone. In early April a request was made to prepare Danville for the arrival of a large number of prisoners General Lee was expected to capture. Instead, Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on the 9th of that month. Union forces ceased the prison compounds two weeks later, and on April 27, General Horatio G. Wright and his VI Corps received the surrender of Danville.

The war, and Danville’s stint as a prison city, was over.

Sources:

“Houses of Horror: Danville’s Civil War Prisons” James I. Robertson, Jr. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 69, No. 3. July 1961

An Account of the Escape of Six Federal Soldiers from the Prison at Danville, VA: Their Travels by Night through the Enemy’s Country to the Union Pickets at Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, in the Winter of 1863-64. W.H. Newlin, Lieutenant Seventy-Third Illinois Volunteers. 1887

Danville’s Civil War Prisons, 1863-1865. Karen Lynn Byrne. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 27 May 1993

Liked this story. Have not read much about the prisons during the war