Most of what we know about the Grove Street Cemetery is owing to Mary Mackenzie Mack and her 1939 book (reprinted and currently for sale at the Danville Museum of Fine Art and History) “History of the Old Grove Street Cemetery, Danville, Virginia”.

Mary was born in Danville on the 2nd of November 1874 to John Graeme and Flora Isabel Lapham Mack. John was a newspaperman who had once worked for the Public Works Department as caretaker for the city’s cemeteries. It is through him that Mary perhaps gained her love and deep respect of local history and the grounds in which the city’s founders were buried. Mary was a school teacher and taught elementary school for over twenty years. She taught at Rison Park Elementary, located on Holbrook Avenue (just a few blocks from where the family lived), and at Robert E. Lee Elementary on Loyal Street. On Grove Street, as well, there was a school, the John L. Berkeley Elementary School, where she also taught and thereby had reason to see the cemetery, then in overgrown and neglected condition, nearly every day.

Mary was born in Danville on the 2nd of November 1874 to John Graeme and Flora Isabel Lapham Mack. John was a newspaperman who had once worked for the Public Works Department as caretaker for the city’s cemeteries. It is through him that Mary perhaps gained her love and deep respect of local history and the grounds in which the city’s founders were buried. Mary was a school teacher and taught elementary school for over twenty years. She taught at Rison Park Elementary, located on Holbrook Avenue (just a few blocks from where the family lived), and at Robert E. Lee Elementary on Loyal Street. On Grove Street, as well, there was a school, the John L. Berkeley Elementary School, where she also taught and thereby had reason to see the cemetery, then in overgrown and neglected condition, nearly every day.

The restoration of the cemetery, which occurred in 1937-1938, was the result, by and large, of Mary’s activism. In the Sunday edition of the Register and Bee, dated March 29, 1936, Mary submitted an article entitled “Danville’s Founding Father’s Lie in Grove Street Cemetery.”

The century-old cemetery on Holbrook and Grove streets is to many people an interesting spot, in spite of the little care and attention that has been given it for many years.

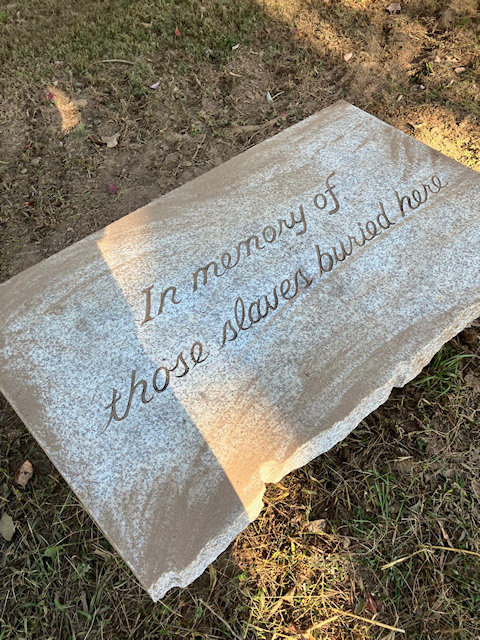

Originally, the cemetery was much larger than it is at present, and the whole area was filled with graves. Slaves were buried in the part on the Grove street side, which the city later salvaged and filled in. There are several houses now on part of the original site.

About twelve or thirteen years ago, the cemetery was ploughed over and grass seed sown. In the process mounds were obliterated and many small stones and markers removed from their locations. There are numbers of unmarked graves on this account.

Mary goes on to present a list of many of those buried here (we’ll discuss that later), and ends her letter with a plea:

Years ago the cemetery was a pretty place, especially in the spring with the ground carpeted with periwinkle and violets and many flowering shrubs in bloom. Instead of a gate there was a stile, which children found quite beguiling.

As only $25.00 a year is appropriated for the upkeep of the cemetery it is necessarily much neglected. … With a larger appropriation for its care, our old cemetery might attain something of its former dignity and be a more worthy resting-place for the forefathers and founders of this city.

Two days later, an editorial appeared written by the Register itself.

When an unofficial suggestion that Grove street cemetery be closed and tis graves moved to Highland Burial Park was made about a year ago, there was immediate objection. Miss Mary Mackenzie Mack’s article on the cemetery in the Sunday Register explains the basis of that objection. The founding fathers of Danville are buried there, and Miss Mack issues a challenge to the City Council to give as good a care to their resting places as Petersburg gives to Blandford, or Richmond to Hollywood, old St. John’s and Shockoe. She reminds the council of the care given the burial ground at Pohick and at Bruton Parish. She calls the roll of the distinguished personages buried in Grove Street Cemetery and of the first families she finds listed on the head stones. She prints the list so there can be no doubt about the matter in any official mind.

The author then put a challenge of its own to the City to take action to secure the cemetery and to give it the care it needs.

These petitions to properly care for the graves of Danville’s early dead were not the first. In fact, a newspaper article in 1915 made a similar appeal, citing the fact that the burial grounds were all but abandoned and yet that was hardly a reason to let it fall into the neglectful state it was in. Five years later, the cemetery was officially closed, but if any improvements were made to it, they could not have lasted long. Two articles of particularly curious interest appeared in the 1920s, illustrating what a lost and forlorn place it had become.

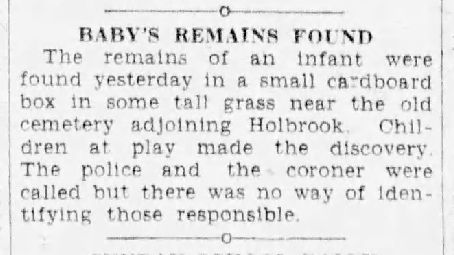

In 1927, the remains of an infant, found in a cardboard box and abandoned in the cemetery were found by a group of children playing there.

Six months later, a “burglar’s outfit” was discovered similarly. “A force of workmen cleaning off the grounds of the old cemetery on Holbrook street, have discovered hidden there a burglar’s outfit. One of the laborers raking up a piece of turf, found the tools, which police say belong to a burglar’s outfit.

Indeed, Mary’s plea might have gone unanswered as well, and the old cemetery swallowed up by encroaching development were it not for two incidents that converged to draw a sense of importance to the decision of what to do with the land, whether it should be moved and built over or preserved.

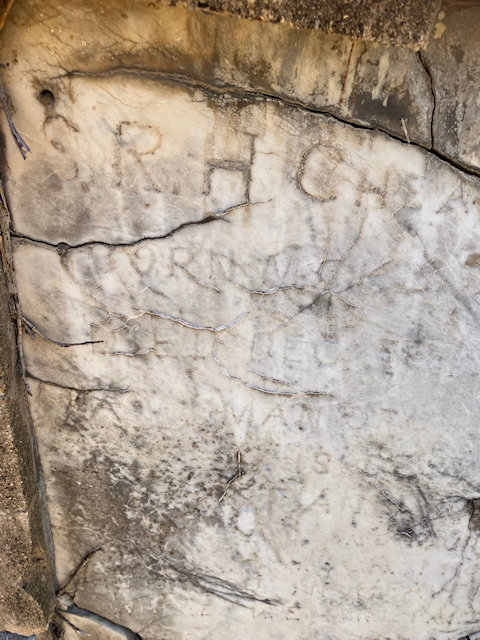

[The last burial in Grove Street Cemetery was that of Susan Ruth Holmes Cheatham in December of 1920. Her son made her tombstone and carved the inscription by hand.)

In 1935, the Works Project Administration, a work-relief program begun by the government during the years of the Great Depression which provided many people, particularly writers and photographers, with work in a dual effort to ease the economic burden on average citizens and, at the same time, to record each state’s cultural and architectural resources. As a part of this program, Mabel Moses, a resident of Pittsylvania County, having read Miss Mack’s “Founding Fathers” article in the paper, felt inspired to write about the Old Grove Street Cemetery.

About this same time, the question of maintenance of the cemetery was answered by the suggestion that the Grove Street graves be removed and transferred to Highland Park, where they would receive perpetual care. This caused an uproar for several reasons. Firstly, many of the grave markers had been lost, both to vandalism and intentionally by the city who deemed the lower grounds easier to care for without the obstacle of head and foot stones. It was also argued that this hallowed ground was set here intentionally and was, in and of itself, a site of historical significance. Even if the graves could be identified, was there anyone around to consult about their removal?

About this same time, the question of maintenance of the cemetery was answered by the suggestion that the Grove Street graves be removed and transferred to Highland Park, where they would receive perpetual care. This caused an uproar for several reasons. Firstly, many of the grave markers had been lost, both to vandalism and intentionally by the city who deemed the lower grounds easier to care for without the obstacle of head and foot stones. It was also argued that this hallowed ground was set here intentionally and was, in and of itself, a site of historical significance. Even if the graves could be identified, was there anyone around to consult about their removal?

An article written by city officials and published in the Bee on the 20th of October 1935 assured citizens that, despite the fact that the city had no knowledge of how many graves were in the cemetery, they promised they could easily identify where graves were located by the interruption of the earth. This is, of course, a fallacy, and the truth remains that, in the case of most cemetery removals, it was common practice simply to move the markers and let the remains lie undisturbed. The people of Danville were not to be fooled.

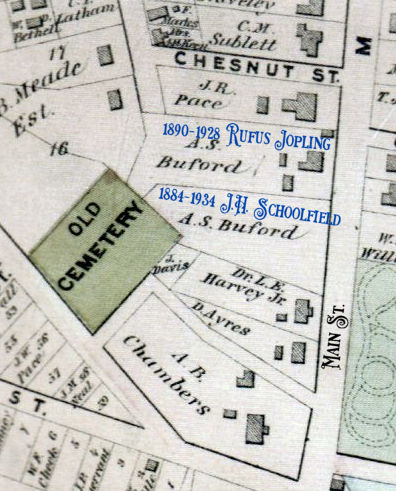

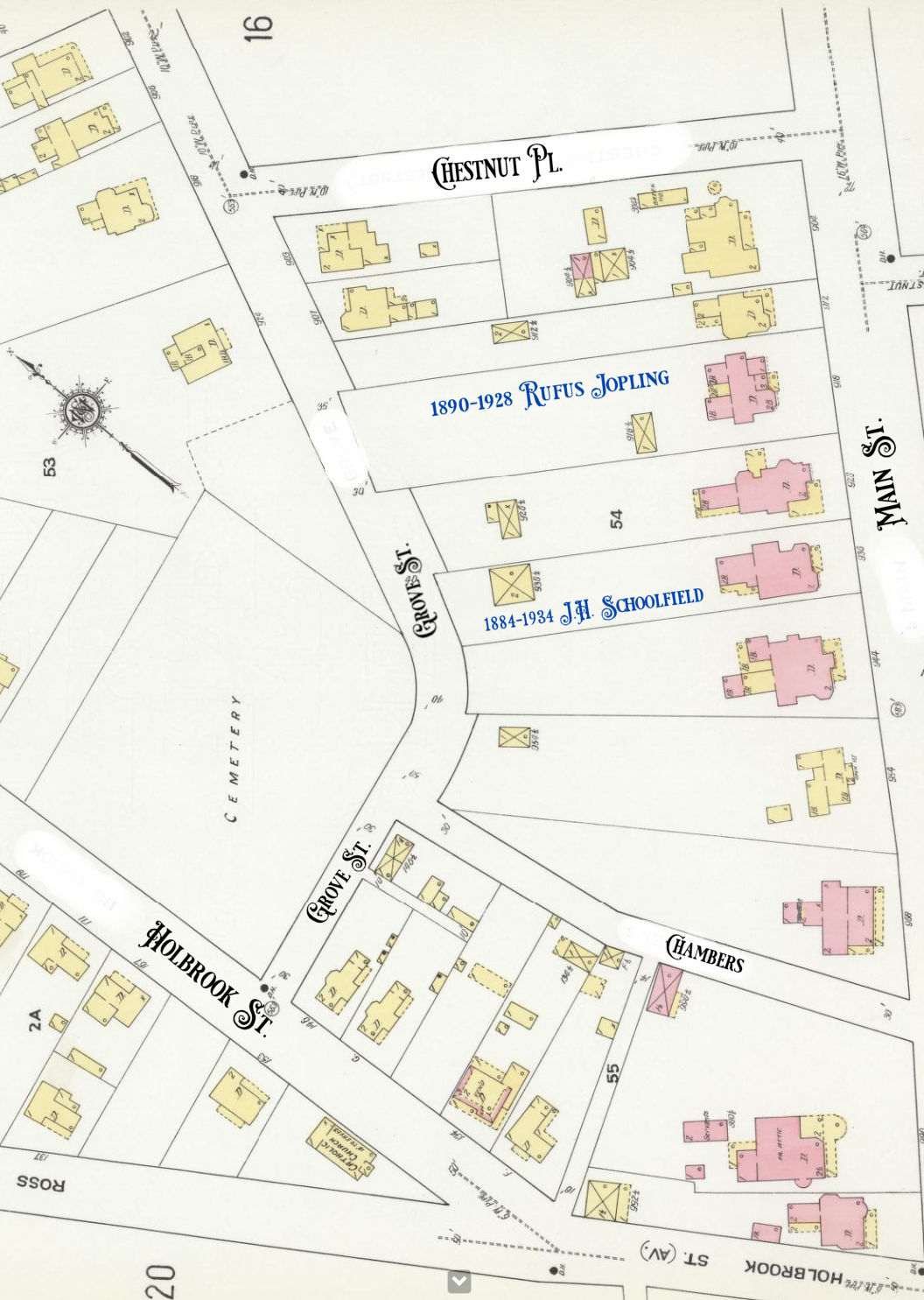

A second problem had also presented itself. Since the 1880s, the city had been trying to establish a firm boundary of the cemetery which had originally bet set just beyond the boundary of the city. As time went on, and people built their suburban homes around and actually on the unclaimed property, the question of ownership became a complicated one. When Mayor Wooding was asked in 1935 to recall what he remembered of its history. “Grove street Cemetery was established,” Mayor Wooding told the newspaper, “before the town was clearly marked. It was one of the boundaries when the city was incorporated in 1854.” He went on to explain that the cemetery was originally much larger and that the city has grown over much of the early burying ground. Mayor Wooding believed that the cemetery once stretched all the way to Main Street, “just across from the Danville Public Library. This was the section in which slaves were buried,” he’d said then. But that section of land, as you can see from the map insert left, was occupied by A.B. Chambers, D. Ayres, L.B. Harvey, Jr., A.S. Buford, and J.B. Pace in 1877. By 1890, one could add Rufus Jopling and J.H. Schoolfield to that list. The question of boundaries had presented itself as a problem when the city made up its mind to continue Grove street from where it ended just behind the Pace home (904 Main Street) to where it reconnected again at Chambers Street. Captain Ballou was hired in 1884 to survey the area and draw a map indicating the connection of the street. (That map was lost and then found in 1910 and since seems to have gone missing again.) The problem yet remained as to how to claim the land back from those who had built homes here. The city had made no claims to the property, despite annexation in 1908. J.H. Schoolfield voluntarily donated the rear portion of his lot in 1894, but as these men were prominent businessmen and local leaders, the issue wasn’t pressed until 1910.

A second problem had also presented itself. Since the 1880s, the city had been trying to establish a firm boundary of the cemetery which had originally bet set just beyond the boundary of the city. As time went on, and people built their suburban homes around and actually on the unclaimed property, the question of ownership became a complicated one. When Mayor Wooding was asked in 1935 to recall what he remembered of its history. “Grove street Cemetery was established,” Mayor Wooding told the newspaper, “before the town was clearly marked. It was one of the boundaries when the city was incorporated in 1854.” He went on to explain that the cemetery was originally much larger and that the city has grown over much of the early burying ground. Mayor Wooding believed that the cemetery once stretched all the way to Main Street, “just across from the Danville Public Library. This was the section in which slaves were buried,” he’d said then. But that section of land, as you can see from the map insert left, was occupied by A.B. Chambers, D. Ayres, L.B. Harvey, Jr., A.S. Buford, and J.B. Pace in 1877. By 1890, one could add Rufus Jopling and J.H. Schoolfield to that list. The question of boundaries had presented itself as a problem when the city made up its mind to continue Grove street from where it ended just behind the Pace home (904 Main Street) to where it reconnected again at Chambers Street. Captain Ballou was hired in 1884 to survey the area and draw a map indicating the connection of the street. (That map was lost and then found in 1910 and since seems to have gone missing again.) The problem yet remained as to how to claim the land back from those who had built homes here. The city had made no claims to the property, despite annexation in 1908. J.H. Schoolfield voluntarily donated the rear portion of his lot in 1894, but as these men were prominent businessmen and local leaders, the issue wasn’t pressed until 1910.

In a city council meeting held in February of 1910, a letter was read written by the city atourney, E. Walton Brown.

In a city council meeting held in February of 1910, a letter was read written by the city atourney, E. Walton Brown.

Gentlemen, some time ago I was requested by resolution to report as to whether Messrs. J.R. Jopling, J.H. Schoolfield and others would be compelled to remove their fences which encroach upon and obstruct the southern side of Grove Street as it extends west of Chestnut, and, if so, the procedure to be adopted by the city to compel such removal.

Without going into detail, I beg to report that after a careful investigation I am of the opinion that the property necessary to extend Grove Street west of Chestnut in a straight line was, in 1884, dedicated to the public for a street, and that all encroachment thereon by Messrs. Jopling, Schoolfield and others is unlawful, and they can be compelled to remove such obstructions therefrom.

By 1910, the street was built, as shown by the Sanborn map of that year (right). In order to accomplish it, the cemetery’s north east corner was filled in, covering the graves that were once there, and the street was paved through connecting to Holbrook Street.

And yet the problem of ownership of the cemetery grounds was far from over. On the 21st of October 1935, an article appeared in the paper entitled “Old Cemetery Ownership is an Open Issue.”

The city is in a quandary over its oldest cemetery, the two acres of hallowed ground on Grove street close to Holbrook where lie buried many of the pioneers of Danville. … When the city engineer made enquiries it was found that there is no record of the city’s title to the cemetery and nobody has been found who can tell whether the land is the city’s or belonged to individuals.

In 1937, another article appeared in the paper describing the grounds which then lay “in sad confusion with broken tombstones toppled over or prostrated, railed in burial squares containing nothing but debris, broken marble slabs lying about the ground and, what is worse, so many graves of the early worthies so obliterated that there s no longer any indication where they were.”

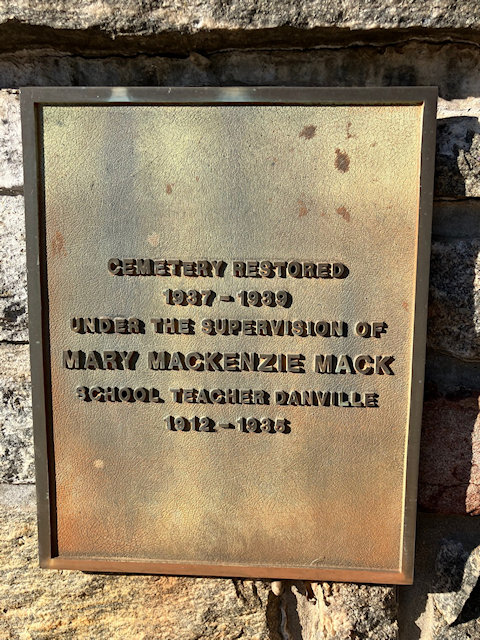

With all this focus on the Grove Street Cemetery and its sad state, the Conservation Committee of the Garden Club of Danville decided to focus on the restoration of the cemetery as its annual project. Partnering with the City Engineer, C. Langdon Scott and the Works Projects Administration, the money was acquired with the federal government providing much of the labor and materials. The Garden Club then contacted Mary Mack and appointed her to be in charge of research on the project. To help, students from Averett were hired and trained, along with many others who came to Danville to help with the project. Relatives of the buried were contacted in order to gain what biographical data was still available. The result of all this hard work and research was Mary Mackenzie Mack’s 1939 publication. Also in 1939, the granite wall was built to enclose the cemetery, complete with wrought iron gates and plaques commemorating the restoration and Mary Mackenzie Mack whose work was central to the restoration. Over the years, other additions have been made, including the restoration of many of the remaining stones, landscaping including heirloom roses, and signage.

With all this focus on the Grove Street Cemetery and its sad state, the Conservation Committee of the Garden Club of Danville decided to focus on the restoration of the cemetery as its annual project. Partnering with the City Engineer, C. Langdon Scott and the Works Projects Administration, the money was acquired with the federal government providing much of the labor and materials. The Garden Club then contacted Mary Mack and appointed her to be in charge of research on the project. To help, students from Averett were hired and trained, along with many others who came to Danville to help with the project. Relatives of the buried were contacted in order to gain what biographical data was still available. The result of all this hard work and research was Mary Mackenzie Mack’s 1939 publication. Also in 1939, the granite wall was built to enclose the cemetery, complete with wrought iron gates and plaques commemorating the restoration and Mary Mackenzie Mack whose work was central to the restoration. Over the years, other additions have been made, including the restoration of many of the remaining stones, landscaping including heirloom roses, and signage.

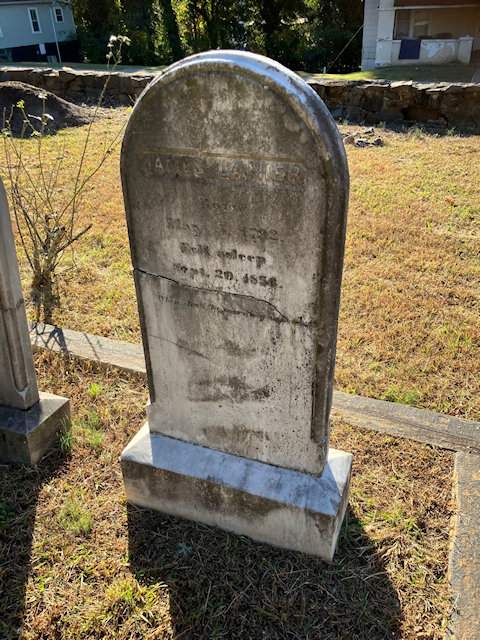

Mary Mack’s inventory included 164 graves. Among them are five members of Danville’s first city council: Robert Ross, Robert Walker Williams, General Benjamin W.S. Cabell, and Dr. George Craghead. Three mayors are buried here: James Lanier, Hobson Johns, and Robert W. Williams. Other prominent names include Chambers, Dame, Patton, Robertson, and Noble.

After the opening of Green Hill Cemetery in 1863 on the land formerly owned and occupied by Nathaniel T. Green, several plots were removed from Grove Street Cemetery, including those of Col. Algernon Sidney Buford, first president of the southern Railroad. The cast iron fence which surrounded his Grove Street Cemetery plot still remains, now empty.

In 1968, the family plot of Nathaniel Wilson was moved to make way for the building of O.T. Bonner Junior High School. Here was the original site of Belle Grade, built in 1823. The house burned in 1889, but the family plot remained. It was relocated to Grove Street Cemetery.

Of those buried at Grove Street are some interesting stories. The favorites have been told and retold, but bear retelling nevertheless.

Priscilla Royal, the earliest known burial, was born in 1818, she was a student at one of Danville’s boarding schools. She had contracted measles and had spent several days in bed. Having recovered enough to join her classmates for dinner, she left her room that evening to join them. After dinner, she returned to her room and found the words “Prepare to meet thy God” written in phosphorus on her bedroom wall. She was so scared, she collapsed and died of a heart attack at the age of 15.

Dr. George Craghead came to Danville in 1826 from Lunenburg county to practice medicine. He fell in love and was engaged, but she broke off the engagement to marry another. He never recovered. He put away his wedding suit and told his sister never to take it out again until he died and then to bury him in it, which she did, 30 years later, in 1843. His brother, William Craghead, also a doctor, was buried beside him 14 years later. (Their shared monument is pictured above.)

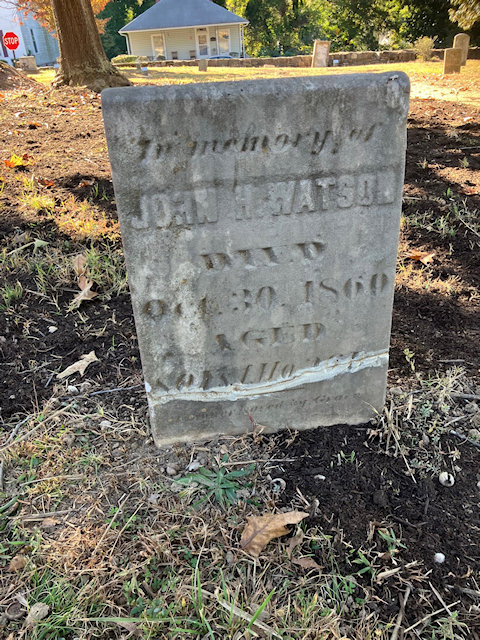

John H. Watson was once sexton of the cemetery. During his watch, he observed the frequent visits of a recently bereft gentleman whose fiancée had died and was buried in one of the vaulted crypts. He visited often, very often, which caught Mr. Watson’s attention. The gentleman would kneel at the side of the grave and spend several minutes there, seeming to dig about it, to kneel and pray and to pay his respects. Something kept him there and kept him coming back, but when Mr. Watson investigated further, he realized a brick had been loosened from her tomb and money stashed inside. The gentleman was an employee of a bank, and, as it turned out, was stealing money and hiding it away in his girlfriend’s above-ground crypt. Mr. Watson turned the man in, and when Watson died in 1860, he was buried so that, even in death, he could keep watch over the deceased young woman whose identity has been lost to time.

[The grave of John H. Watson looks over the tomb of a young woman whose identity is lost to time.]

Another woman whose name has been lost to time was nearly buried here twice. On the occasion of her first funeral, she had made directions that she should be buried in a dress with a particular bit of lace collar that was very old and had some sentimental meaning to her. Upon seeing her, her daughter raised an objection and demanded the collar be removed, at which point the mother sat up and made her own argument in favor of the dress and collar. She had merely been in a trance, and, upon recovering, managed to live many more years.

For a period of time between 1890 and 1904, the city of Danville conducted its own executions. The city sergent at the time was Patrick Henry Boisseau. Unlike executions in other places, those conducted under Mr. Boisseau’s direction were not public. He felt that execution was a solemn affair and not one to be celebrated. The executions took place in a vacant space between the jail and courthouse, where a 25 foot plank fence was erected to prevent spectators. The only other people present to watch were twelve witnesses who were called to attend, selected similarly as jurors for a trial, and no fewer than two doctors. When the execution was over, the prisoners were cut down and hidden away until night fall when, if they had not been claimed by family (as some were) they were buried secretly at night. As Grove Street Cemetery was yet out of town and no longer used by the more respectable citizens at that point, it is speculated (but cannot be proven) that some of those burials, including those perhaps of the murderers Jim Lyles and Margaret Lashley who together plotted to kill her husband, may have been secretly buried here.

For a period of time between 1890 and 1904, the city of Danville conducted its own executions. The city sergent at the time was Patrick Henry Boisseau. Unlike executions in other places, those conducted under Mr. Boisseau’s direction were not public. He felt that execution was a solemn affair and not one to be celebrated. The executions took place in a vacant space between the jail and courthouse, where a 25 foot plank fence was erected to prevent spectators. The only other people present to watch were twelve witnesses who were called to attend, selected similarly as jurors for a trial, and no fewer than two doctors. When the execution was over, the prisoners were cut down and hidden away until night fall when, if they had not been claimed by family (as some were) they were buried secretly at night. As Grove Street Cemetery was yet out of town and no longer used by the more respectable citizens at that point, it is speculated (but cannot be proven) that some of those burials, including those perhaps of the murderers Jim Lyles and Margaret Lashley who together plotted to kill her husband, may have been secretly buried here.

Thankfully, Grove Street Cemetery is now well maintained as a cherished local landmark and, with any luck, will be preserved for many generations to come. It is only a pity that we no longer know the names of those who might otherwise be honored by their interment here.

Sources:

Grove Street Cemetery, Danville VA’s Oldest, Clara Fountain and Sandra March. 2019.

History of Old Grove Street Cemetery, Danville, Virginia, Mary Mackenzie Mack. 1939.

Newspaper references found in the Danville Register, Danville Bee and other newspaper archives at Newspapers.com and GenealogyBank.com