T

he spiritualist movement in America began as a reaction to dogmatic canon that tended to discouraged the idea that the common man could have contact with the souls of the dearly departed. Heaven was a long way away, after all. And yet there were many who quietly held onto hope that their loved ones were not quite out of reach and, furthermore, that they actually wanted to communicate.

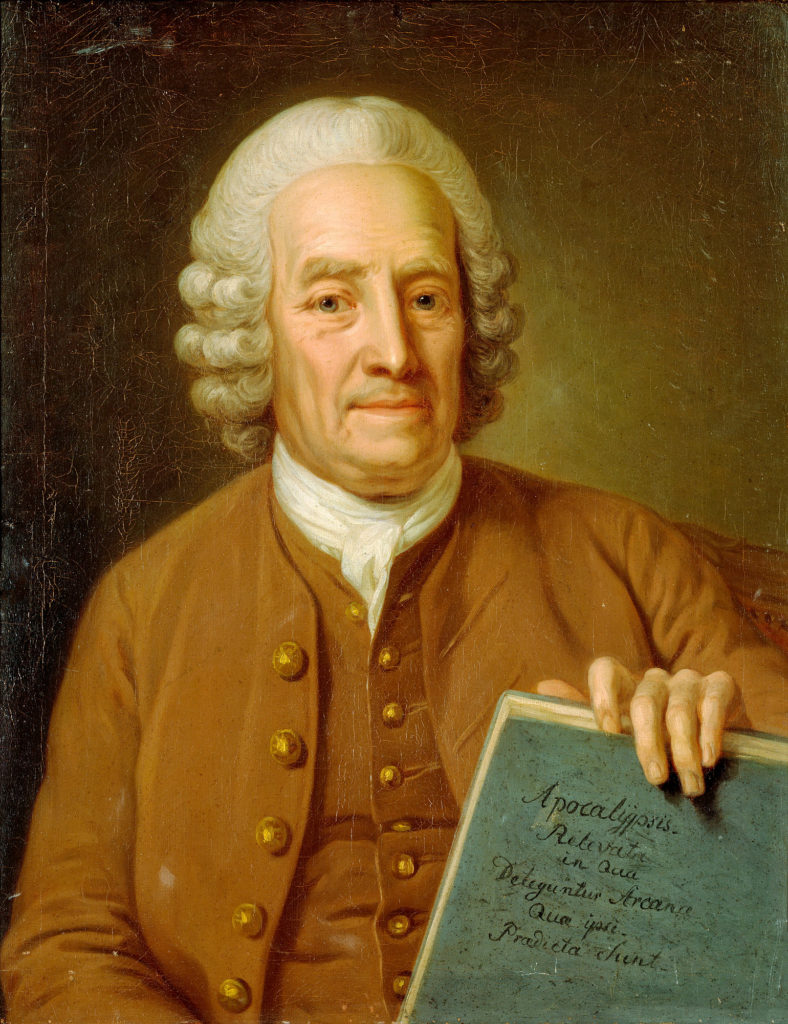

Fodder for such thought was encouraged by men like Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish born inventor, scientist, physiologist, and esteemed engineer who also had some interesting ideas about man’s relationship with God. Prior to Swedenborg’s claim to have received a vision directing him to restore Christianity in its true form, he was, in fact, a highly respected man of science and thought. Among the philosophies he promulgated, and which were particularly appealing to early adherents of the spiritualist movement were the ideas that 1) Heaven consisted of hierarchical degrees (celestial, spiritual, and natural) 2) children who died at a young age went directly to Heaven, and 3) that, just beyond the veil of death, there exists a plane where the souls of the departed are prepared for Heaven or Hell. It was here, in this middle place, that spirits were allowed to communicate with the living. By 1840, many of these ideas were embraced by those who hoped to maintain some connection with those they had lost. The age of the séance was born.

Fodder for such thought was encouraged by men like Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish born inventor, scientist, physiologist, and esteemed engineer who also had some interesting ideas about man’s relationship with God. Prior to Swedenborg’s claim to have received a vision directing him to restore Christianity in its true form, he was, in fact, a highly respected man of science and thought. Among the philosophies he promulgated, and which were particularly appealing to early adherents of the spiritualist movement were the ideas that 1) Heaven consisted of hierarchical degrees (celestial, spiritual, and natural) 2) children who died at a young age went directly to Heaven, and 3) that, just beyond the veil of death, there exists a plane where the souls of the departed are prepared for Heaven or Hell. It was here, in this middle place, that spirits were allowed to communicate with the living. By 1840, many of these ideas were embraced by those who hoped to maintain some connection with those they had lost. The age of the séance was born.

It thrived, too, and by 1897 there were some eight million followers of the Spiritualist Movement in the United States and Europe. The late Victorian era also saw a proliferation of fraud. Men and women touting themselves as mediums promised grieving mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, brothers, sisters, and lovers a chance to commune once more with those they mourned. Celebrities of the day such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini began making tours and visiting seances in order to reveal fraudulent mediums. By the 1930’s many of the most popular of the Spiritualist movement’s mediums had either been revealed or had confessed their fraudulent dealings to the public. The fervor, therefore, had died down, but it was not dead yet.

In 1952 rumors of séances conducted by a group of students at Averett Baptist College (now Averett University) which was then an all-girls school, though it had begun to take a few male day students. It was on March 1 that the mischief began when one member of the party, a Miss Merle Goad, rang up one of her classmates, including Grove Street (806) resident, Carole Stuart, to say she was getting a group of people together to go on a gravedigging expedition. Fellow student Jay Ford Pigg knew just the place for it, too.

In 1741, John Pigg, a Virginia colonist entered for “400 acres on the north side of the south fork of Staunton River,” later renamed by the family who had settled upon it. For centuries, the family maintained the land near the Pigg River and, on it, a family cemetery. There are few memorials recorded in the Pigg family cemetery. Find-A-Grave lists nine in total, the last being Jay Ford Pigg’s grandparents who died in 1926 and 1935. The earliest marked graves were those of that original forebear Paul Pigg who was buried there in 1767 and Jay’s 4th and 5th Great Grandfathers whose memorials both dated 1785.

With the Pigg Family Cemetery in mind, the group of students borrowed “a prominent Danville man’s car,” a black Dodge sedan, and drove in the daylight hours to the site near Dry Fork.

At first it was stated to police that they began digging merely out of curiosity, but Pigg, it seemed, had a good idea where they would find something worth digging for. “There ought to be bones in this one,” Pigg was stated as saying. Not all the graves were marked, but it is reasonable to assume this one was, and that it was one of the older graves, at that. This was his family. It’s hard to imagine he would have dug up someone he had actually known or that he hadn’t thought through how long it might take for a body, coffin and all, to decompose. It seems they all took turns digging, first a foot and then two deep, and then three … at which point they struck something. From the grave they recovered a skull, two fragments of bones, a handle of the coffin, and a metal plaque that read “rest in in peace”.

Miss Goad took the skull to her own home. Upon its being discovered by her family, she was told she must return it to the cemetery. The family piled in their own car and she was made to reburry it. This was on a Saturday. On Monday, certain other members of the group returned to the cemetery and recovered the skull once more.

And then the seances started. Of all the statements made regarding the event, there are no details to illuminate what took place during the seances. We know there were two of them, one each on March 3 and 4th, and that they occurred in the day schooler’s room. Perhaps it was Jay, known as “Heze” by his friends, who hoped to learn more about the family on whose land he and so many generations of his family before him had lived (and whose grave he had desecrated). Or, perhaps, the skull and bones were meant only to provide a little ambience to the events already premeditated. It’s unclear if there was anyone else involved in the séance apart from the six graverobbers. Séances were not illegal. Graverobbing was, despite young Pigg’s claim that he had a right to dig on his own property.

And then the seances started. Of all the statements made regarding the event, there are no details to illuminate what took place during the seances. We know there were two of them, one each on March 3 and 4th, and that they occurred in the day schooler’s room. Perhaps it was Jay, known as “Heze” by his friends, who hoped to learn more about the family on whose land he and so many generations of his family before him had lived (and whose grave he had desecrated). Or, perhaps, the skull and bones were meant only to provide a little ambience to the events already premeditated. It’s unclear if there was anyone else involved in the séance apart from the six graverobbers. Séances were not illegal. Graverobbing was, despite young Pigg’s claim that he had a right to dig on his own property.

After the second séance, and with word spreading like wildfire as to what the youth had done, two of the young men, including “Heze” burned the objects in the school’s furnace.

And then came the police. The youths were thoroughly lectured. Their crime, a state felony, was punishable by up to ten years in prison. Charges were filed, capiases for their arrests were issued, and bonds were set at $1,000. The youth, all but one of them being students of Averett, were expelled. When the case reached the Circuit Court, the judge, in a closed-door session, reduced the charges from violation of a sepulcher to trespassing, and they were fined $50 each. Perhaps he felt that the interruption to their educations was enough.

Jay Hezekiah “Heze” Pigg passed away in 1993. He was not buried in the Pigg family cemetery.

(For more Averett related hauntings, be sure to read our companion post.)

Sources:

The Bee (Danville, Virginia), “County Cemetery Incident Involves 4 Boys, 2 Girls”, 27 Mar 1952, Pg. 1

The Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), “Six Danville Students Indicted on Charges of Graverobbing”, 28 Mar 1952, Pg. 1

The Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), “Six Former Students Get Lecture, Fine in Grave Robbery”, 20 May 1952, Pg. 1

Spiritualism

History of Pittsylvania County, Virginia