The Old West End and Holbrook-Ross historic neighborhoods will soon be joined by another officially designated historic district in Danville. The mill village of Schoolfield was established in 1903 by Dan River Mills, the textile giant who began operations in 1886 as Riverside Cotton Mills and who shuttered its operations in 2006 in order to take production overseas. Their exodus ended the careers of thousands of Danville’s citizens and left hundreds of buildings vacant and neglected, as well as several important buildings that were ultimately destroyed.

Fourteen years after the company’s closure, the neighborhood of Schoolfield is at last getting the recognition it deserves. Unlike the Old West End, whose historic significance is represented by each of its historic homes and buildings independently, most of which were built by the rich and influential of Danville’s history, the 900-plus buildings that comprise the village at Schoolfield are significant collectively in the narrative they tell of working class people and the industry they supported, and vice versa.

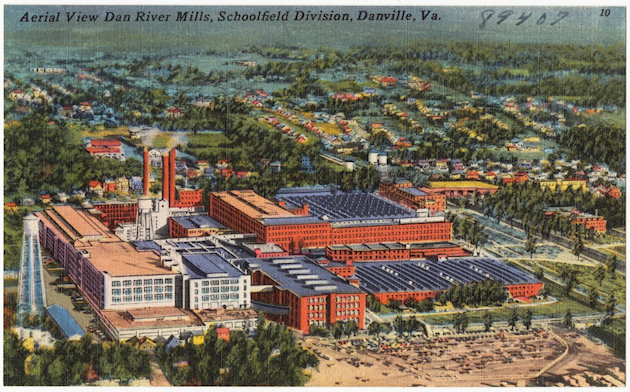

Dan River Mills began as Riverside Cotton Mills with operations along the Dan River on Memorial and Riverside Drives, powered by the river’s current. With the advent of electricity, Riverside built the Dan River Power and Manufacturing company in 1895 which offered the opportunity for expansion further from the River. Mill founders acquired land outside the city limits (and beyond control of City regulations) where they built a powerhouse and dam, an 82 acre mill, a commercial “main street”, and residential housing for employees.

Homes in Schoolfield were constructed in phases. The first wave of 445 houses came in the years between 1903 and 1909 with those of management being larger and more decorative, while those of the common millhand being simpler wood-frame structures of three or four rooms.

Starting in the nineteen-teens, attitudes about Mill town housing, and those who occupied them, began to change. According to Ina Dixon, of Storied Capital, one of the consulting firms working on the historic designation project, wrote: “During this time, many mill towns like Schoolfield suffered reputationally as millhands increasingly rubbed against nearby middle-class sensibilities. Degrading millhands as lint-heads or a “social type” to be pitied, a growing southern middle class in the early 1900s wanted mill companies to do better at training their workers in the ways of urban society.”

In 1917 Dan River Mills hired professional planners and developers to establish a self-sufficient village, where millhands were encouraged to “adopt middle-class habits and values.” In fact, with everything from housing, to recreation, to social activities, schools, churches, and childcare provided within the village limits, such “urbanizing” was hardly avoidable. Dan River Mills created the perfect atmosphere for training up its next generation of workers simply by excluding all other possibilities.

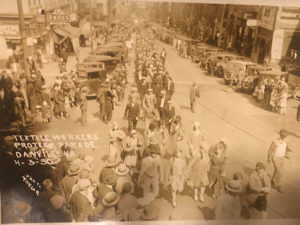

Development and expansion came to a grinding halt in 1930. The lean years following the stock market crash of 1929 lead to a decline in demand. Workers were expected to work longer hours without additional pay. In the fall and winter of 1930, 4,000 mill employees went on strike. Because the mill played multiple roles, including that of employer and landlord, the result was eviction for many. In December of 1930, the executives of Dan River Mills handed out eviction notices to 31 Schoolfield families.

“As you know,” the notices read, “these premises are used by us for the employees of our company, and as you are not now an employee of this company and will not in the future occupy such a position with us, we desire that you should vacate the premises as promptly as possible.”

Expansion of Schoolfield continued until 1969 with the construction of the Regional Headquarters building in 1967 and the 1969 warehouse. Among the losses since Dan River, Inc’s closure in 2006 are the 1916 YMCA building and recreation center which was demolished to make way for a CVS; Hylton Hall, built in 1919 as a boarding house for the mill’s single female employees, destroyed in a fire in 2012; and of course the industrial buildings including Mills no. 1, 2, 3, 4 and a portion of Mill no. 5, which were salvaged for bricks.

Despite these losses, the mill village remains largely intact and has an important story to tell of Virginia’s industrialization and post war Reconstruction.

Survey work of the 972 properties has been ongoing since early February and is scheduled to wrap up in the next few weeks, a job that was originally estimated to take two years. After the survey work is done, there follows many months of additional study and consideration before the designation will be decided upon and made official.

Survey work of the 972 properties has been ongoing since early February and is scheduled to wrap up in the next few weeks, a job that was originally estimated to take two years. After the survey work is done, there follows many months of additional study and consideration before the designation will be decided upon and made official.

Designation is strictly honorary and puts no restrictions on what property owners can do with their homes or property apart from already existing zoning ordinances. Designation would encourage much welcome preservation efforts, however, and would provide property owners incentives for rehabilitation through state and federal tax programs.

For more on this work, see the Register and Bee’s coverage of 3 February 2020, and for a more in-depth explanation of Schoolfield’s role in the history of Danville and the state of Virginia, you can read the wonderfully informative preliminary submission made publicly available by the Virginia Department of Historical Resources.