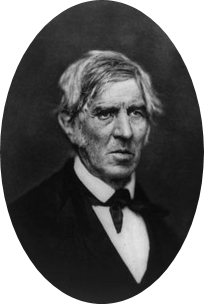

George Washington Whitman was born in 1829, the sixth of nine children born to Walter and Louisa Van Velsor Whitman. The Whitmans moved often, typically between New York and New Jersey, their lives frequently upended by the requirements of seeking financial security during precarious times. Walter Whitman, Sr. (pictured left) was a carpenter of modest success, and by the time his eldest children had reached the age of ten or eleven, they were taken out of school and trained to help him in the carpentry business, though they each, eventually, chose different paths (and with mixed success).

George Washington Whitman was born in 1829, the sixth of nine children born to Walter and Louisa Van Velsor Whitman. The Whitmans moved often, typically between New York and New Jersey, their lives frequently upended by the requirements of seeking financial security during precarious times. Walter Whitman, Sr. (pictured left) was a carpenter of modest success, and by the time his eldest children had reached the age of ten or eleven, they were taken out of school and trained to help him in the carpentry business, though they each, eventually, chose different paths (and with mixed success).

Indeed, eldest son, Jesse, struggled all his life to support himself much less other members of his family, eventually going mad and dying in an insane asylum. Walter, Jr., the second eldest, was more fortunate (though not initially). Identified as Walt to differentiate him from his father, he gravitated toward the world of law and letters, procuring employment as an office boy for a law partnership and, later, as an assistant for the Patriot, a weekly newspaper in Long Island.

Indeed, eldest son, Jesse, struggled all his life to support himself much less other members of his family, eventually going mad and dying in an insane asylum. Walter, Jr., the second eldest, was more fortunate (though not initially). Identified as Walt to differentiate him from his father, he gravitated toward the world of law and letters, procuring employment as an office boy for a law partnership and, later, as an assistant for the Patriot, a weekly newspaper in Long Island.

As daughters, Mary and Hanna had the unenviable responsibility of marrying well in order to assist with the support of their family. Hannah (pictured left) married a struggling artist with a reportedly bad temper and an easily bruised ego. Neither did Mary succeed in marrying happily or wealthily.

Brother Andrew was a little too much like his eldest brother to assist the family’s financial requirements in any beneficial way. Andrew proved to be every bit as depraved as Jesse, having entangled himself with a prostitute with whom he had several children, none of which he could adequately support. He eventually died of throat cancer in 1863. “Jeff” did moderately well, following his elder brother Walt into the printing business before finding work as a land surveyor and topographical engineer. The youngest of the Whitman sons, Edward, was developmentally impaired, having suffered a traumatic birth which had left him paralyzed on is left side. And so it was that when Walter, Sr. died suddenly on July 11, 1855, Walt, Jeff, and George were the only children in a position to support their mother, their younger brother, and their often needy and impoverished siblings.

Brother Andrew was a little too much like his eldest brother to assist the family’s financial requirements in any beneficial way. Andrew proved to be every bit as depraved as Jesse, having entangled himself with a prostitute with whom he had several children, none of which he could adequately support. He eventually died of throat cancer in 1863. “Jeff” did moderately well, following his elder brother Walt into the printing business before finding work as a land surveyor and topographical engineer. The youngest of the Whitman sons, Edward, was developmentally impaired, having suffered a traumatic birth which had left him paralyzed on is left side. And so it was that when Walter, Sr. died suddenly on July 11, 1855, Walt, Jeff, and George were the only children in a position to support their mother, their younger brother, and their often needy and impoverished siblings.

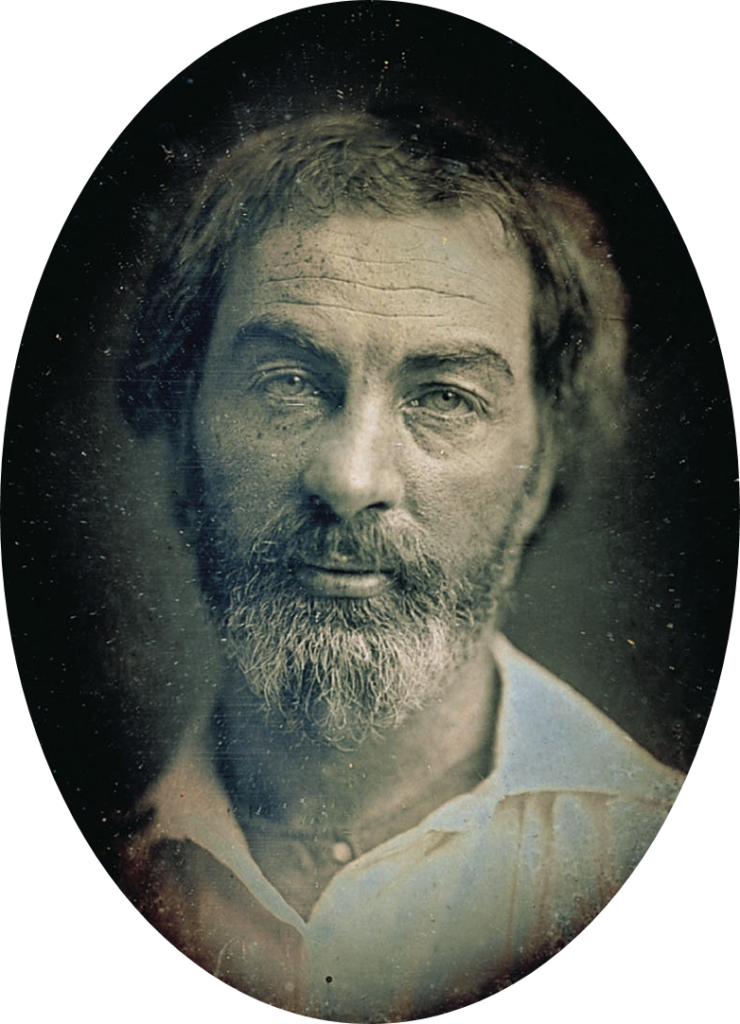

It was just a few days prior to Mr. Whitman’s death that Walt’s first major work was published. It was not an immediate success. What Leaves of Grass did not produce in money it produced in criticism. Victorian cultural aesthetics bristled at Walt’s use of anatomical references in metaphor, and his use of free verse was a challenge to those who held the examples of Wordsworth and Tennyson (both poet laureates and wildly appreciated) as the standard of both poetic form and theme. Rather than helping the family, Walt’s work scandalized them.

It was just a few days prior to Mr. Whitman’s death that Walt’s first major work was published. It was not an immediate success. What Leaves of Grass did not produce in money it produced in criticism. Victorian cultural aesthetics bristled at Walt’s use of anatomical references in metaphor, and his use of free verse was a challenge to those who held the examples of Wordsworth and Tennyson (both poet laureates and wildly appreciated) as the standard of both poetic form and theme. Rather than helping the family, Walt’s work scandalized them.

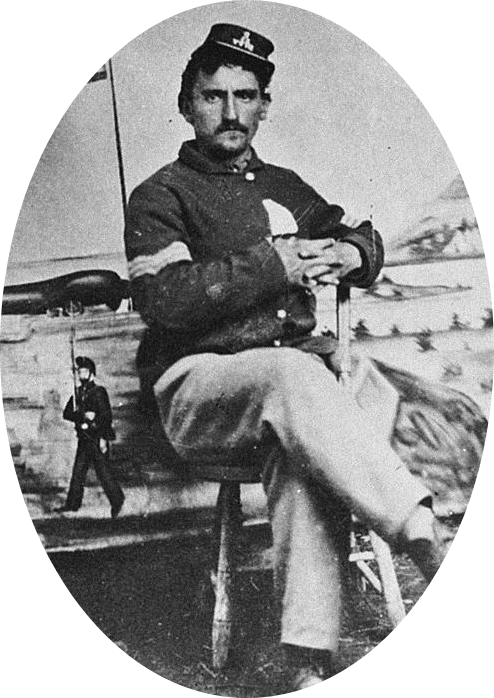

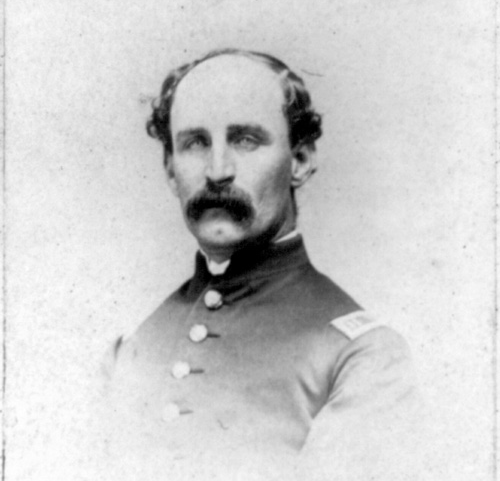

When the Civil War broke out in April of 1861, Walt was too old to fight and, the pen being mightier than the sword, chose to support the preservation of the union of the United States through his writing. Jeff, who was 28 at the time, chose not to enlist and somehow escaped the New York draft in 1863. In 1864, however, his name came up. Rather than enlist, he paid the $400 commutation fee, effectively buying his way out of service. George, however, had no hesitation and enlisted in the Thirteenth New York State Militia. A post contracted for a mere 100 days, the approximate length he and others believed the conflict would last.

When his three months’ commission was up, George returned home to Brooklyn. By this time the war was in full swing, and the carnage suffered at Bull Run, combined with the apparent tenacity of the Southern armies, seemed to indicate this would be no short-run conflict as previously supposed. George re-enlisted, joining the Fifty-First Regiment of New York Volunteers. The battles of Roanoke Island and New Bern in February and March of 1862 earned him a promotion to second lieutenant. By September, after the battles of Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Chantilly, South Mountain, and Antietam, battles he witnessed firsthand, he rose to first lieutenant, and by November he was promoted to captain. In December, at the battle of First Fredericksburg, a shell fell on the ground before George’s feet and exploded, wounding him.

When his three months’ commission was up, George returned home to Brooklyn. By this time the war was in full swing, and the carnage suffered at Bull Run, combined with the apparent tenacity of the Southern armies, seemed to indicate this would be no short-run conflict as previously supposed. George re-enlisted, joining the Fifty-First Regiment of New York Volunteers. The battles of Roanoke Island and New Bern in February and March of 1862 earned him a promotion to second lieutenant. By September, after the battles of Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Chantilly, South Mountain, and Antietam, battles he witnessed firsthand, he rose to first lieutenant, and by November he was promoted to captain. In December, at the battle of First Fredericksburg, a shell fell on the ground before George’s feet and exploded, wounding him.

Meanwhile, back in Brooklyn, the Whitman family, who had suffered the death of Andrew in September, kept a close vigil on the reports of the war in the papers. When one morning in December Walt saw the name G.W. Whitmore on the list of wounded, he instinctively knew the misnomer was meant to indicate his brother, and he immediately left for Fredericksburg to find him.

Walking all day and night, unable to ride, trying to get information, trying to get access to big people … Walt at last arrived at the hospital to find that his brother had returned already to his regiment. George’s injury proved, after all, to have been a mere flesh wound to his cheek. Walt did not leave, however. The scene within and about the hospital at Chatham (Lacy House), compelled him to remain.

Began my visits among the camp hospitals in the Army of the Potomac, under General Burnside. Spent a good part of the day in a large brick mansion on the banks of the Rappahannock, immediately opposite Fredericksburg. It is used as a hospital since the battle, and seems to have received only the worst cases. Outdoors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I noticed a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc. — about a load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each covered with its brown woolen blanket. In the dooryard, toward the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel staves or broken board, stuck in the dirt.

Walt stayed at Lacy House until the 28th of December (1862), when he left for Washington, D.C. There he found work in the army paymaster’s office, a position that allowed him to carry out the mission he had come on purpose to perform—that of volunteering as a nurse in the army hospitals. For the next several years, Walt Whitman dutifully nursed the sick and wounded, wrote for the public and privately, and, too, occasionally writing to influence political opinion as he met with “big people” (those like Abraham Lincoln, a fan himself of Walt’s work) until the final battles of the war and the dreadful day he learned of the capture of his brother’s regiment on September 30, 1864 at Poplar Grove Church, Virginia.

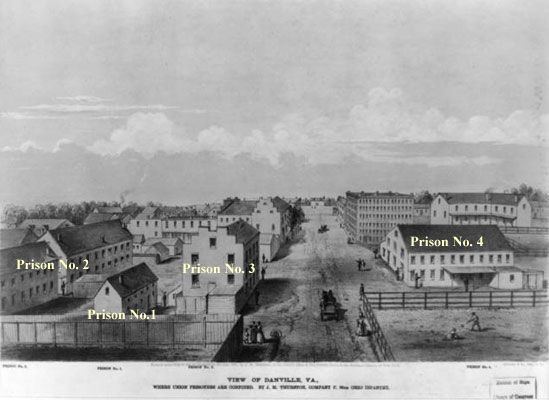

Upon capture, the Fifty-First was initially taken to Richmond’s notorious Libby Prison, where all prisoner processing took place, and, according to James I. Robertson in his 1961 article for The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography titled “Houses of Horror: Danville’s Civil War Prisons” it is entirely likely that the regiment was looking forward to better conditions rather than worse as they made their way, by train, to Danville, whose prisons had been established there just eleven months prior.

Robertson describes the journey as one which took a full twenty-four hours, “since the track was dangerously bad and the locomotives, wheezing steam and burning twice their normal amount of wood, could make barely twelve miles per hour. Each boxcar contained seventy prisoners and four guards, and the weight of the cars and their occupants often proved too much of a strain on the engines” which would have to stop and rest. The weight of the train with its human cargo was also occasionally too much for the tracks themselves, which would sometimes spread apart and have to be re-spiked before the train could continue on.

Arriving at the new prison in Danville, exhausted and hungry, the soldiers were shown to their quarters, which consisted of “six brick or wooden tobacco factories, each three stories high”. 650 men were kept on each floor of the factory which had been stripped of all amenities. Those which had retained their heating stoves may or may not have had wood to fuel them. The floors, upon arrival, were caked thick with the remnants of the tobacco that had been there months before, of the spittle of the men who chewed it, and of the excrement of the animals whose job it was to carry it there and take it away again, or to feed on it or nest in it once the men had gone. Conditions were bad. Food had already grown scarce and very expensive in Danville even before the arrival of the prisoners on November 13, 1863. By the time George arrived nearly a year later, and approaching the coldest part of the year, matters were looking bleak. Besides the vermin, lice, rodents, fleas, and the diseases which had found home in the litter and waste left behind by the enterprise which had once occupied the warehouses, there were much deadlier pestilences as well, smallpox among them, which had overtaken the city in the winter of 1863-1864. But that fire had, thankfully, extinguished itself by the time George arrived.

George’s first letter home was written from Libby Prison on the 2nd of October. “Here I am perfectly well and unhurt, but a prisoner,” he wrote. “I am in tip top health and Spirits, and am tough as a mule and shall get along first rate, Mother please don’t worry and all will be right in time if you will not worry.”

The letter was a comfort, but the slow rate of overland delivery meant that conditions might be entirely different by the time his family received it. Indeed, that first letter arrived weeks later than the initial report, printed in the Brooklyn Daily Union on the 3rd of October which told of heavy losses but lacked the details necessary to give the Whitman family any comfort. The following day, the same paper printed an update to its previous post, announcing that the number of those wounded, captured, or killed was nearing 2,000 men, and, moreover, that more than half of those men had been taken prisoner. The Whitman family likely received George’s first letter around the 29th of October, nearly a month after it was sent. A second letter, written from Libby Prison, never arrived home. George wrote again on the 23rd, from Danville (quoted below), and then a fourth time on the 27th of November. This letter, now lost, didn’t reach his family until January.

Danville Va,

October 23d 1864

Dear Mother.

I wrote you a line from Libby Prison a few days after I was taken prisoner, but think it doubtfull if you received it. I was taken, (along with almost our entire Regt. both Officers and men) on the 30th day of September, near the Weldon Rail Road, but am proud to think that we stood and fought untill we were entirely surrounded … I am very well indeed, and in tip top spirits, am tough as a mule, and about as ugly, and can eat any amount of corn bread, so you see, dear Mother that I am all right, and my greatest trouble is that you will worry about me, but I beg of you not to frett, as I get along first rate. Please write to Lieut. Babcock Co. F of our Regt. and tell him to send my things home by Express.

Much love to all.

G. W. Whitman

“Their situation, as of all our men in prison, is indescribably horrible,” Walt would later write. “Hard, ghastly starvation is the rule. Rags, filth, despair, in large open stockades, no shelter, no cooking, no clothes—such is the condition of masses of men, in some places two or three thousand, and in the largest prison (Andersonville) as high as thirty thousand confined. The guards are insufficient in numbers, and they make it up by treble severity, shooting the prisoners literally just to keep them under terrorism.” Danville suffered the coldest winter on record in 1864-1865. One Federal officer recorded in his diary in December of 1864 that the river had frozen over “solid enough to make a safe crossing on the ice.” Many prisoners suffered frostbite in the uninsulated warehouses.

It’s no surprise then, that, by January, George was very ill. Stricken by “lung fever”, he was transferred to one of the military hospitals, where he recuperated for the six weeks prior to his release. It was only in the hospitals where good food, clean linens and clothing, and the hope for real rest (and just as often escape) could be realized.

Three hospitals for the wounded were set up in Danville. The first was located on the corner of Jefferson Avenue and Loyal Streets. At the time, the only building which stood there was that of the Danville Female Academy (where the old Danville General Hospital, now razed, once stood). It is also possible that there was a temporary tent hospital erected on land situated on one of the other corners as was the case with the second military hospital which had been established “on the hill overlooking the old Danville & Western Railway shops”. A third hospital was deemed necessary to alleviate the spread of smallpox during the epidemic that occurred in the Winter of 1863-1864. This hospital was located somewhere near Lee and Whitmell streets, within easy reach of reach of the cemetery.

George’s personal effects arrived home on December 26, 1864. “It stood some hours before we felt inclined to open it,” Walt wrote in his diary. “Towards evening, mother & Eddy looked over the things. One could not help feeling depressed. There were his uniform coat, pants, sash, &c. There were many things reminded us of him. Papers, memoranda, books, nick0nacks, a revolver, a small diary, roll of his company, a case of photographs of his comrades (several of them I knew as killed in battle) with other stuff such as a soldier accumulates.”

Walt and Jeff immediately set about trying to organize an exchange of prisoners that would result in George’s freedom. As it turned out, plans for such an exchange were already in the works, and, during the last week of February 1864, all of the Danville prisoners were sent up to Annapolis. Freed, however, was not discharged, and George was given a thirty day furlough before he was expected to report back to his commanding officers. He was hardly fit for it, though, for his time in prison had tolled greatly upon his health.

Upon arriving in Annapolis, George was hospitalized a second time. In a letter written to a family friend, Walt described his brother as in “almost what I would call fair condition, if it were not that his legs are affected—it seems to me it is rheumatism, following the fever he had—but I don’t know—He goes to bed quite sleepy & falls to sleep—but then soon wakes, & frequently little or no sleep that night—he most always leaves the bed, & comes downstairs, & passes the night on the sofa … He is going to report to Annapolis promptly when his furlough is up—I told him I had no doubt I could get it extended, but he does not wish it—He says little, but is in first rate spirits.”

By May, George had returned to duty and was promoted to major. He remained in Alexandria and was assigned command of the Prince Street Military Prison.

On July 27th, 1865, George was released from military service along with the rest of his regiment. He returned to Brooklyn and to his mother’s home, but he had a difficult time shaking off the war. Indeed, it seems he would much rather have returned to it and to the familiar camaraderie of his brother soldiers than be an agent of his own devices. George eventually entered into the speculative construction business with a partner but struggled to make a success of it. In 1867, George began working as an inspector of gas pipe lines even as he continued in the construction business. The venture at last began to realize some capital, and George used the funds to build a three-story home for his mother just in time for his luck to turn again. In 1868, he was nearly bankrupt, but, the following year, things were once more looking up for him and he began to experience financial solvency for perhaps the first time in his life.

In 1871, he married Luisa Orr Haslam. The couple set up house in Camden and soon had Mrs. Whitman living with them, along with George’s disabled brother, Edward. After Mrs. Whitman’s death in May of 1873, Walt moved in with his brother’s family.

George and his wife had two children, neither of which survived infancy. In 1876, they had a son whom they named Walter, but he was not strong and only survived eight months. At the child’s funeral, as friends and family came to view the body, Walt sat nearby entertaining the children who accompanied their parents as they paid their respects. “You don’t know what it is, do you, my dear?” Walt asked of one little girl who appeared not to know what to make of the sight of a dead child, nor of the ceremonious homage to him. “We don’t either,” was the insightful answer he provided for her.

Walt Whitman died on March, 26, 1892. On August 9 of that year, George lost his wife. Three months later, Edward died as well. George spent the rest of his life alone and crippled, suffering from the rheumatism that had plagued him since his imprisonment in Danville and the illness that struck him so savagely while he was here, a reluctant Danville resident. He died on December 20, 1901.

Sources:

“Here I am … a Prisoner:” The Capture of Walt Whitman’s Brother. Emerging Civil War. www.emergingcivilwar.com Tim Talbott. 19 Sep 2022

“I am Well and Hearty”: Walt Whitman’s Brother in the Civil War. History Net. www.historynet.com Gordon Berg. 18 August 2011

“Walt Whitman at Chatham.” National Park Service. www.nps.gov 7 September 2021

The Civil War Letters of George Washington Whitman. The Walt Whitman Archive. www.whitmanarchive.org Jerome M. Loving. 1975

“Houses of Horror: Danville’s Civil War Prisons” James I. Robertson, Jr. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 69, No. 3. July 1961

An Account of the Escape of Six Federal Soldiers from the Prison at Danville, VA: Their Travels by Night through the Enemy’s Country to the Union Pickets at Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, in the Winter of 1863-64. W.H. Newlin, Lieutenant Seventy-Third Illinois Volunteers. 1887

Danville’s Civil War Prisons, 1863-1865. Karen Lynn Byrne. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 27 May 1993

Yes. And thank you for reading! Prison no. 6 still stands at the corner of Lynn and Loyal Streets. It does not look much like it used to do. I’ll be writing more about Danville’s Civil War Prisons in the next issue of the Gazette, along with photos, so stay tuned!

I enjoyed this story. Did any of the tobacco factories used as prisons survive?