What follows was written in partnership and cooperation with the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History and funded, in partnership with Virginia Humanities.

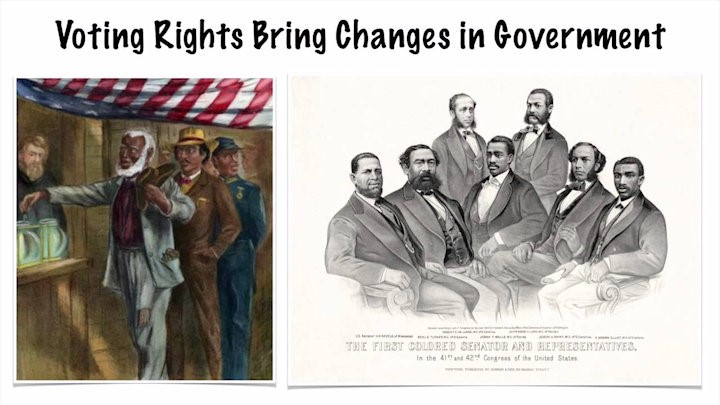

The roots of the Civil Rights movement go back to Reconstruction. For several years following the abolition of slavery, black Americans found themselves free to pursue opportunities previously denied them. Protected by the 14th Amendment of 1868, which guaranteed equal protection under the law, followed in 1870 by the 15th Amendment which ensured all (men) the right to vote, many black Americans pursued educations, positions in public office, and made significant inroads in their efforts to achieve lives of purpose, prosperity, and equality. At the same time, the Civil War had decimated many white families, and the resentment that had begun with the loss of the war was fueled by the hardships put upon them as a punishment for the South’s act of treason. Though the deep south is often blamed for having the worst reputation for racial tensions, Virginia, or Military District 1, as it was known after the Civil War was a hotbed of resentment and political and legal maneuverings intended to subvert the North’s impositions of laws regarding protections for freed slaves.

With the election of Andrew Johnson, those efforts of subversion took on a more nationalized effort. Jackson’s Black Codes, essentially rescinded the rights granted black men by the 14th and 15th Amendments. Arguments began to mount for “separate but equal” policies which led, in 1896, to the Supreme Court decision to uphold segregation.

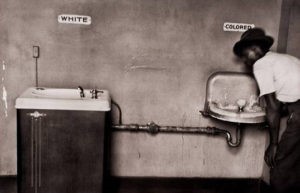

Services provided for black citizens were distinct and separate from those for whites, from restaurants and libraries to schools and hospitals and everything in between. This separation caused a rift in the United States that is still palpable today. Separate lives lead to separate cultures, to separate narratives about what life in America means and the ease by which it is lived. But separate never for one minute meant equal. The best jobs, the best neighborhoods, the best schools, the best services, however necessary they were, were reserved for white citizens. Libraries and schools, which were paid for from property taxes, were better funded in white communities. Resources and services were therefore necessarily sub-par.

Services provided for black citizens were distinct and separate from those for whites, from restaurants and libraries to schools and hospitals and everything in between. This separation caused a rift in the United States that is still palpable today. Separate lives lead to separate cultures, to separate narratives about what life in America means and the ease by which it is lived. But separate never for one minute meant equal. The best jobs, the best neighborhoods, the best schools, the best services, however necessary they were, were reserved for white citizens. Libraries and schools, which were paid for from property taxes, were better funded in white communities. Resources and services were therefore necessarily sub-par.

World War II began to shift the tide, if ever so slightly. Considering the dire consequences had the United States failed in its initiatives in the second world war, and considering the necessity of engaging upon those initiatives with a united front, Harry Truman in 1948 issued Executive Order 9981, which was intended to end segregation and discrimination within the military. In 1954, the Supreme Court retracted its position on “separate but equal” and declared segregation illegal in public schools.

Though segregation was now illegal, Brown v. Board of Education did very little to change public sentiment or mitigate the prejudice, malice, and outright violence perpetrated upon the black community. Appeals to the city council were made for more representation in government, but despite these pleas, Danville remained segregated a full nine years after the Supreme Court declared segregation to be illegal, largely as a result of Senator Harry F. Byrd and the “Southern Manifesto” which provided massive resistance toward Civil Rights reform measures.

Though segregation was now illegal, Brown v. Board of Education did very little to change public sentiment or mitigate the prejudice, malice, and outright violence perpetrated upon the black community. Appeals to the city council were made for more representation in government, but despite these pleas, Danville remained segregated a full nine years after the Supreme Court declared segregation to be illegal, largely as a result of Senator Harry F. Byrd and the “Southern Manifesto” which provided massive resistance toward Civil Rights reform measures.

In 1955, the movement began to pick up steam when Rosa Parks, a 42 year old black woman refused to give up her seat to a white man while riding a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Her arrest sparked outrage and placed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a Montgomery Baptist minister at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1957 Dr. King established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The purpose of the organization was to provide leadership training and civic education programs, including voter registration drives and instruction in how to conduct peaceful protests to those working toward equality for African Americans.

In 1957 Dr. King established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The purpose of the organization was to provide leadership training and civic education programs, including voter registration drives and instruction in how to conduct peaceful protests to those working toward equality for African Americans.

After hearing the concerns of African Americans in Danville and listening to their stories, Dr. King made his first of four visits to Danville. On March 26, 1963, Dr. King spoke in the City Auditorium to a crowd of 2,500.

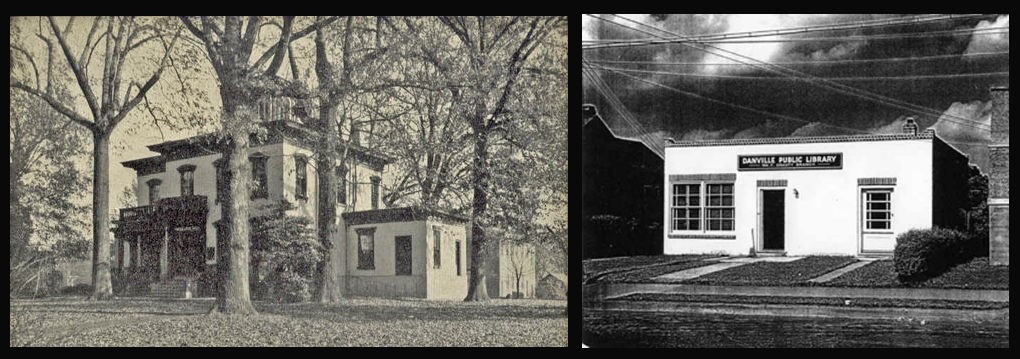

The result of Dr. King’s first visit was the organization of peaceful protests which began in April when sixteen students from Langston High School staged a sit-in at the Danville Public Library. The protesters, led by fellow student Robert A. Williams, were frustrated by the lack of resources and by the outdated and obsolete materials available to them in their own segregated library. The students were asked to leave. When they refused the library announced it was closing for the day, and it did not reopen again until a federal judge ordered all libraries to be open to all patrons four months later. The library reopened, but under a “vertical” policy. Tables and chairs were removed. Patrons could enter but they could not sit and linger.

On May 31st, the Danville Christian Progressive Association was formed, and on June 5, a group from the newly formed organization marched into City Hall and occupied the City Manager’s office. The next day, temporary injunctions were issued (later made permanent) based on an 1859 statute which prohibited “conspiring to incite the colored population of the State to acts of violence and war against the white population.” A special grand jury was called to uphold the statute and on June 7, members of the Danville Christian Progressive association were indicted and arrested on bonds of $5,000 each.

Then, on the evening of June 10th, a prayer vigil was held in response to the indictments. While the peaceful crowd gathered in an alley across the courthouse, police were busy deputizing garbage men and arming them with billy clubs. The prayer was not finished before police and deputized sanitation workers let loose on the crowd, violently striking peaceful protesters with lead filled billy clubs and opening fire hoses, shooting water at a force strong enough to break skin and knock men to the ground. Forty-seven people were injured, fifteen were hospitalized. The event, known as Bloody Monday, brought national attention to Danville’s struggle for racial equality. The protests continued.

Dr. King returned to Danville on July 11, where he spoke to a gathering at the High Street Baptist Church. “We have certainly been with you in spirit,” he said to his audience that day, “and we have agonized with you as you have faced the brutality and ruthlessness of a vicious police force. I have seen some brutal things on the part of policemen all across the south in our struggle, but very seldom if ever have I heard of a police force being as brutal and vicious as the police force here in Danville, Virginia.”

“It took Danville many years to admit that they actually beat the demonstrators who were fighting for our human rights,” Reverend Lawrence Campbell said in an interview with Virginia Currents a National Public Radio program. Reverend Campbell is one of the founders of the Danville Christian Progressive Association and author of the book, 1963: A Turning Point in Civil Rights. His wife was severely beaten by the chief of police during the events of June 10, 1963.

In recent years, the city has done more than admit what happened. In July of 2019, the Danville Police Department publicly apologized for the events of that day. Reverend Campbell received that apology on behalf of African American citizens of Danville.

In recent years, the city has done more than admit what happened. In July of 2019, the Danville Police Department publicly apologized for the events of that day. Reverend Campbell received that apology on behalf of African American citizens of Danville.

That apology raises interesting questions for those of us who are invested in resolving the disparities that still exist in our community and in our country. As we’ve once again been reminded, the fight is far from over and much needs to be done yet in order realize the unity that was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream.

This article was written by V.R. Christensen for the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History for their Artist in Residence program in June of 2020. The DMFAs Artist in Residence program is funded by Virginia Humanities.