“Mrs. Landon Carter Berkeley, 83, died here early Friday … at her home on Holbrook Avenue after a long decline in health.” So read The Danville Bee of February 10, 1937.

The article goes on to describe Mrs. Berkeley’s achievements, those which included her advantageous marriage to Landon Carter Berkeley in September of 1880, and the 58 years she spent in Danville as a leader of women’s movements that included her involvement as a charter member of the Wednesday Club as well as the Music Study Club. Perhaps of all of her accomplishments, what she is remembered for now, more than three quarters of a century after her death, is that she was the first student to enroll at Wellesley College, and it is owing to the record keepers at Wellesley who have graciously supplied us with the material for this post.

Anne Poe Harrison was born September 9, 1856 to John Poe Harrison and Mrs. Ann Cook Harrison at Dewberry in Hanover county, Virginia. Like the man she would marry, her father was a lawyer and had worked on the staff of Governor John Letcher (1860-1864). Anne’s childhood home of Dewberry was situated just north of Richmond and was directly in the path of the contending armies during the Civil War. “At Dewberry, the Harrisons had seen the armies of both sides march back and forth, had heard the guns in action, and on one occasion their home had been shelled by Federal artillery, although the only shell which struck the house failed to explode.” Anne never forgot the terror of battle, more particularly since the Civil War’s contentions had taken her father (Mr. Harrison died in 1861 of typhoid, though some later claimed he died in battle at Drewery’s Bluff in 1864). When the fighting ended, the Harrison estate was left in ruins. The family of women, fatherless and now penniless, too, had to find a way of sustaining themselves.

“Under the guidance of a talented young teacher, Miss Jenny Nelson,” Anne’s son Norborne reported at Wellesley’s 75th Fund campaign held at the Waldorf in New York City in 1947, “they undertook to qualify themselves as teachers, to become breadwinners and to extricate themselves and their families from their grim surroundings.”

By 1875, “Miss Nelson had taken them as far as she could when she learned that Mr. Henry Fowle Durant, a Boston lawyer, proposed to open Wellesley to afford young women ‘opportunities for education equivalent to those provided in colleges for men.’ (A mission contemporaneous with the establishing of Cambridge’s Newnham and Girton Colleges and the fight for women’s education in England.) Miss Nelson, on behalf of her pupils, immediately reached out to him.” Her concern, at first, was merely for her students, but upon speaking with Mrs. Durant, who was sympathetic to the plight of women in the post-war South, a job was offered to her as well as a place within the school for any pupils she chose to bring with her.

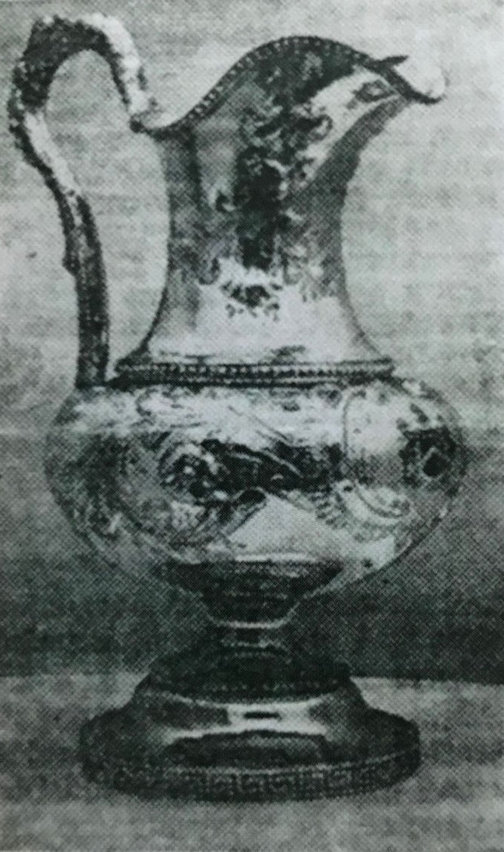

The $250 tuition and boarding fee was insurmountable for many students who might have accepted the Durants’ invitation, however, and those who chose to make the sojourn northward were forced to pawn what little personal property that still remained to them. One of Anne’s remaining treasures was a silver pitcher, an heirloom from her father’s family and which was hidden from Union soldiers during the war. It was sold, and Anne soon set out for Boston. After a grueling journey, the girls arrived to learn that the college would not be opening for another two weeks. They were graciously invited to stay with the Durants for the duration.

“The night before formal registration, Mr. Durant got out a big book, called his guests together, and said that, since they had made such sacrifices to get there, he wanted them to be the first to register, and my other being the older, he wanted her to register first of all. And so it was that she was the first to sign the rolls.”

The women followed an accelerated course, and, rather than going through a formal graduation, left as soon they felt qualified to seek employment. Miss Nelson, after teaching at Wellesley for a time, returned to Virginia as the first Head Mistress of Chatham Hall and continued to send students to Wellesley including other members of her own family. Anne took teaching appointments in Gainesville, Alabama and then West River, Maryland before moving back to Virginia where she married Landon Carter Berkeley in 1880. Mr. Berkeley, in a sweeping gesture of devotion, hunted down the Harrison’s prized silver pitcher, uniquely marked by a family crest, and returned it to her as a gift.

Norborne, as part of his remarks, observed that his mother’s story, “unlike most civil War stories, can be told with equal satisfaction on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line as showing kindness, generosity and breadth of vision on the part of distinguished educators of the North and resourcefulness and an appreciation of the value of an education on the part of young women of the South when their way of life had been swept away and they were surrounded by ruin and despair. It shows, too,” he further opined, “as is most often the case, though at times we are reluctant to admit it, that there are really worth-while people on both sides of almost any line you can draw whether it be one of geography, race, creed, or color.” Mrs. Durant, wife of the college’s first president, felt similarly. According to a newspaper article which ran in the Richmond Times-Dispatch of January 18, 1948, “Mrs. Durant apparently felt strongly that living and learning together would help women of the North and South heal the wounds of war and build a stronger nation.”

Norborne, as part of his remarks, observed that his mother’s story, “unlike most civil War stories, can be told with equal satisfaction on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line as showing kindness, generosity and breadth of vision on the part of distinguished educators of the North and resourcefulness and an appreciation of the value of an education on the part of young women of the South when their way of life had been swept away and they were surrounded by ruin and despair. It shows, too,” he further opined, “as is most often the case, though at times we are reluctant to admit it, that there are really worth-while people on both sides of almost any line you can draw whether it be one of geography, race, creed, or color.” Mrs. Durant, wife of the college’s first president, felt similarly. According to a newspaper article which ran in the Richmond Times-Dispatch of January 18, 1948, “Mrs. Durant apparently felt strongly that living and learning together would help women of the North and South heal the wounds of war and build a stronger nation.”

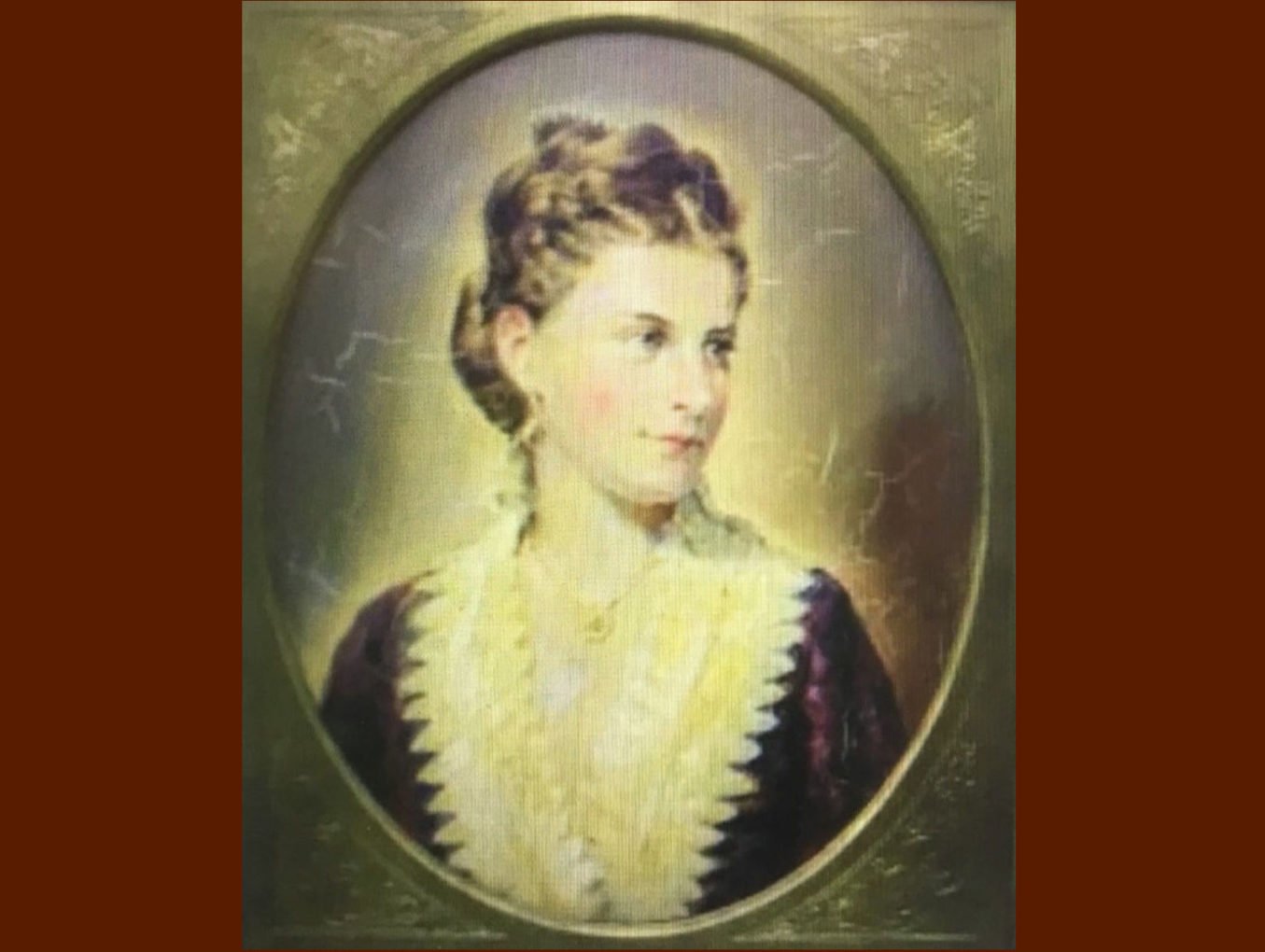

Norborne Berkeley attended the University of Virginia where he received his law degree. He was vice-president of the Bethlehem Steel Company in 1947, and his address was part of a ceremony in which he gifted to Wellesley College the portrait of his mother (see featured image) painted by Frederick Roscher of Bucks County, Pennsylvania from a miniature made of her while she attended Wellesley. The portrait hung in the reception room of the Admissions Office “where prospective students may see the first student who came to Wellesley”. A distinguished honor she would no doubt have been proud of.

Wellesley College’s original College Hall was destroyed by fire in 1914, taking with it many of it’s early records. No proof of Anne Poe Harrison Berkeley’s registration still exists, and yet the College has proudly held onto what proofs of provenance they have been able to reassemble since that time. Our thanks to Katie Lamontagne and the archivists at Wellesley College for providing the information for this piece, and to Clara Fountain who took the initiative of reaching out to them.

The sources provided to us include:

Mrs. Landon Berkely obit from The Danville Bee of 10 Feb 1939.

Various letters between administrative staff at Wellesley College and certain members of the Berkeley family.

A copy of Norborne Berkeley’s remarks given at the Wellesley’s 75th Fund campaign held at the Waldorf in New York City in 1947, provided to Wellesley by Mr. Berkeley’s brother in law, Mr. Elliott Randolph, M.D.

Article from The Townsman, Wellesley, Mass of 16 December 1948 “Portrait of First Student Presented Local College”

Article from The Times-Dispatch (Richmond) 18 January 1948 “Virginian First Wellesley Student”

Mrs. Berkeley lived at 150 Holbrook Avenue. Thank you for reading and for your question. It reminded me to cross-link the pieces.

Where on Holbrook did she live?