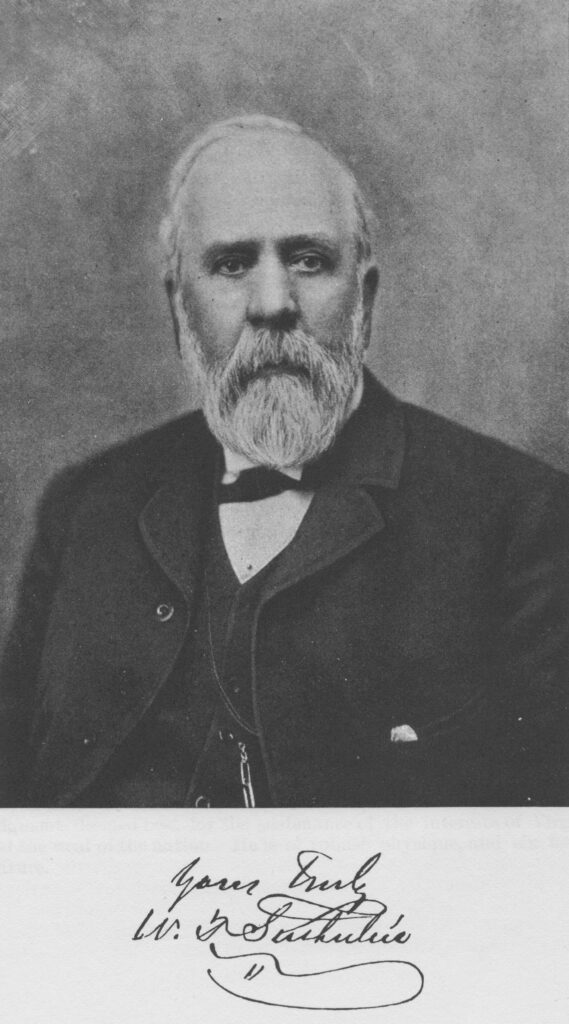

William T. Sutherlin was no more than thirty-six when his imposing new house was completed. At this comparatively young age he had already proved his acumen in local civic and business affairs. He had served as alderman and mayor, and was recognized as a leading banker, tobacconist and entrepreneur. He was a delegate to the state convention that passed, albeit reluctantly, the Ordinance of Secession on April 17, 1861. reluctantly, the Ordinance of Secession on April 17, 1861. Sutherlin did not serve in the active military, but was appointed instead as Quartermaster of Danville’s depot (Sutherlin rose to the rank of major), his duties included oversight of supplies such as food and medicine, and weapons and from Danville’s arsenal.

William T. Sutherlin was no more than thirty-six when his imposing new house was completed. At this comparatively young age he had already proved his acumen in local civic and business affairs. He had served as alderman and mayor, and was recognized as a leading banker, tobacconist and entrepreneur. He was a delegate to the state convention that passed, albeit reluctantly, the Ordinance of Secession on April 17, 1861. reluctantly, the Ordinance of Secession on April 17, 1861. Sutherlin did not serve in the active military, but was appointed instead as Quartermaster of Danville’s depot (Sutherlin rose to the rank of major), his duties included oversight of supplies such as food and medicine, and weapons and from Danville’s arsenal.

In his later years he served as president of the Virginia State Board of Agriculture and was noted for his support of higher education and the promotion of Danville’s interests while serving in the Virginia House of Delegates.

Considering William Sutherlin’s position as a business and social leader of Danville, it is not surprising that his move from Wilson Street to Main Street in 1858 portended a general move of the local population onto Main Street and adjacent streets.

In 1856, when Levi Holbrook sold Sutherlin the property his house now occupies, the land lay just within the town’s corporate limits. The completed dwelling included office and residential space for Mr. Holbrook in exchange for the interest-free five-year credit he granted Mr. Sutherlin for the lot. In 1860 its assessed value was $12,500.

The size and lavish detail of the new residence were unprecedented in Danville. It was designed by F.B. Clopton, a Richmond architect and engineer who cited Sutherlin, Col. Claudius Crozet, C.E., and the directors of the Danville Hotel Company as references in his 1859 Richmond city directory advertisement.

The size and lavish detail of the new residence were unprecedented in Danville. It was designed by F.B. Clopton, a Richmond architect and engineer who cited Sutherlin, Col. Claudius Crozet, C.E., and the directors of the Danville Hotel Company as references in his 1859 Richmond city directory advertisement.

Today, the location of the house in the middle of a broad tree-shaded yard makes it the architectural focal point for Danville’s gracious Main Street. In the waning days of the Confederacy, it shared with the long-demolished Benedict House on Wilson Street some of the day-to-day activity of the government. The Sutherlin House has become nationally famous for its historical associations, serving as the last Executive Mansion for Jefferson Davis as well as the site of the president’s final meeting with his cabinet in Danville before receiving word of Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox. Included on the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic places, the structure is regarded also as a fine example of the antebellum Italian Villa style which is characterized by the use of shallow hipped roof, bracketed cornices, smooth stuccoed walls, hood moldings, and the almost universal use of the square cupola. Except for the addition of low inconspicuous wings, the house is unaltered on the exterior.

After the death in 1911 of Mrs. Sutherlin, the former Jane E. Patrick who survived her husband by seventeen years, the community learned that the property was to be sold. The threat of demolition and subdivision of a site that was considered even then a historic site of importance, galvanized into action some of the city’s early advocates of historic preservation who chartered the Danville Confederate Memorial Association in December 1912. The under the leadership of the president, Frank Talbott, and four other officers—R.A. James, A.B. Carrington, J.E. Perkinson, and C.G. Holland—and with the moral and financial assistance of the local chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and others, a successful campaign was mounted to purchase the property. For its help in preserving the newly-designated Confederate Memorial, the Ann Eliza Johns Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was provided a meeting room in the Sutherlin Mansion.

After the death in 1911 of Mrs. Sutherlin, the former Jane E. Patrick who survived her husband by seventeen years, the community learned that the property was to be sold. The threat of demolition and subdivision of a site that was considered even then a historic site of importance, galvanized into action some of the city’s early advocates of historic preservation who chartered the Danville Confederate Memorial Association in December 1912. The under the leadership of the president, Frank Talbott, and four other officers—R.A. James, A.B. Carrington, J.E. Perkinson, and C.G. Holland—and with the moral and financial assistance of the local chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and others, a successful campaign was mounted to purchase the property. For its help in preserving the newly-designated Confederate Memorial, the Ann Eliza Johns Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was provided a meeting room in the Sutherlin Mansion.

The building received limited care until 1928 when the Danville Public Library was moved there and interior modelling was begun to suit its needs.

The building received limited care until 1928 when the Danville Public Library was moved there and interior modelling was begun to suit its needs.

On April 2, 1960, a group of sixteen African American students, taking inspiration from the sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina and in Petersburg, Virginia, protested against segregated publicly-funded spaces in Danville, stopping first at Ballou Park and then at the Danville Public library, then referred to as the Confederate Memorial Library.

The sit-in became a motivating event for a larger local civil rights movement that developed over the next three years, and peaked in Danville in 1963.

After the sit in, the editors of the Danville Register complained that the students entered the library on the anniversary of Jefferson Davis’s occupation of the Sutherlin Mansion at the end of the Civil War. The editors saw the students’ sit-in as “an invasion of the Confederate Memorial Mansion,” and then accused the students of breaking the “racial calm” that had existed in the city since November 1883, referring to the year of the Danville Massacre that left four Black men dead.

The following week, the Black students and the NAACP experienced retaliation for their actions. On the night of April 9, crosses were burned on the front lawns of Loyal Baptist Church and Reverend and local NAACP leader Doyle J. Thomas’s house.

In response, the Black community of Danville held a mass meeting at Loyal Baptist Church, which drew over 350 attendees and got the attention of other NAACP leaders. On April 11, the city escalated the sit-in case to a full-blown legal struggle by voting to close the library rather than integrate. Two days later on April 13, the NAACP sought a federal injunction against all segregated public facilities in Danville. The plaintiffs in the case were Chalmers Mebane, Gladys Giles, Wayne Louis Dallas, Robert Williams, and Jerry Williams, all students who participated in the sit-in.

On May 5, local federal judge Roby Thompson heard arguments in the case that the NAACP had filed against the city. Judge Thompson ruled in the favor of the plaintiffs and ordered that the library be open to African Americans but delayed the implementation of the injunction until May 20 to give the city time to appeal to a higher court.

While the students and African American community celebrated their court victory, the white citizens of Danville scrambled to devise a solution that would keep the Confederate Memorial Library white-only.

On May 19, the Danville city council made a last-minute attempt to stop the injunction by voting to close all Danville libraries. A local judge also set a date for a city-wide referendum where Danville voters would decide if the city would continue to have a public library; the referendum was set for June 14. Overwhelmingly, Danville’s white citizens voted for the library to remain closed.

In response to the referendum, the Danville Bee published an editorial trumpeting victory for the white segregationists of the city with many references to the Confederacy and Danville’s history in the Confederacy. Their interpretation of the overwhelming vote to close the library was that the majority of Danville citizens wanted to hold firmly to Jim Crow and that the NAACP and the federal judiciary were akin to the federal troops of the Civil War.

In September after a federal court ruling, both libraries were reopened and integrated, but the chairs had been removed so patrons could not sit and spend time at the libraries.

At the same time, in an effort to exclude the poorer classes from the libraries, it was announced that all patrons would need to acquire new library cards by October 1, 1960, at a cost of $2.50 to use the libraries themselves or 50 cents for use of the bookmobile only.

For decades, the Sutherlin Mansion represented history as a weapon of white supremacy, and the sit-in fundamentally challenged it.

In 1971, anticipating the move of the library to its present location downtown, the Danville Chapter of the Virginia Museum obtained permission from Danville City Council to use the Sutherlin House as a museum. Efforts to restore and adapt the house as the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History began shortly after the library relocated in 1974. Since then, members and staff, inspired by the vision of the museum’s first director, Dr. James W. Jennings, who died in 1984, have created a dynamic historical and cultural attraction which annually draws more than 20,000 visitors from across the nation and around the world.

Throughout the historic house care has been taken to restore mid-nineteenth-century luster to rooms that include a number of opulent furnishings and personal effects owned by the Sutherlins. Interpretation of the structure’s role in the final week of the Confederate government is much in evidence, notably in the furnished second-floor bedroom where Jefferson Davis slept, and in the document he penned—his last official proclamation to the citizens of a dying nation. Elsewhere, wings added to the building while it was a library have been adopted as an auditorium, gift shop, and art galleries, helping realize the museum’s role dual role as exhibitor of Fine Arts and historical artifacts.

Throughout the historic house care has been taken to restore mid-nineteenth-century luster to rooms that include a number of opulent furnishings and personal effects owned by the Sutherlins. Interpretation of the structure’s role in the final week of the Confederate government is much in evidence, notably in the furnished second-floor bedroom where Jefferson Davis slept, and in the document he penned—his last official proclamation to the citizens of a dying nation. Elsewhere, wings added to the building while it was a library have been adopted as an auditorium, gift shop, and art galleries, helping realize the museum’s role dual role as exhibitor of Fine Arts and historical artifacts.

The grounds of the Sutherlin house, graced by a remnant of the old trees known as “the Grove” which once crowned this site and the nearby Ridge, have been enhanced for many years through the continuing efforts of the Garden Club of Danville in conjunction with the city’s Department of Public works.

Reproduced with permission from Gary Grant from his book, Victorian Danville – Fifty-Two Landmarks: Their Architecture and History (1977 Mary Cahill and Gary Grant) and updated by present directorial staff at the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History, December 2024.