George W. Talley was the neighborhood postman in the early years of the 20th century. His summer uniform would have been much like the example above. He lived for a time on Holbrook Avenue, though he resided on Colquhoun Street at the time of his death.

It was around 1903 that Mr. Talley began delivering mail, and he carried out his route dutifully for fifteen years, long after contracting tuberculosis sometime in the 19-teens. In May of 1918, Danville’s Board of Health raised questions to Mr. Talley’s employer regarding the potential risks of his carrying mail from door to door and advised he be given a pension until he was properly recuperated. The post office department agreed to take the Board’s advice under consideration, but it was a moment too late. On the 2nd of June 1918, while delivering mail on Stokes Street, Mr. Talley collapsed and died. He had suffered a pulmonary embolism, leaving behind a wife, Annie, with three children at home – 21-year-old Bertha, 13-year-old Lelia, and Ernest, who was just eleven.

Even though tuberculosis was known to be a contagious disease from the 1880’s, it remained the leading cause of death through the first two decades of the 20th century. The statistics for Virginia were particularly alarming. In 1909, the same year that the first effective vaccine was developed, the State Health Board was reorganized and for the first time, statistics in the state began to be gathered. It was also in 1909 that the first sanitorium in the state was opened in Roanoke, which heavily influenced the way in which those statistics were recorded. Anyone who exited the sanitorium was listed as “discharged” even if the reason for that discharge was death – which was often the case in the early years of its establishment. It took another nine years before a second sanitorium was opened – this one to serve the African-American population. Two years later, in 1920, a third State operated sanitorium opened in Charlottesville.

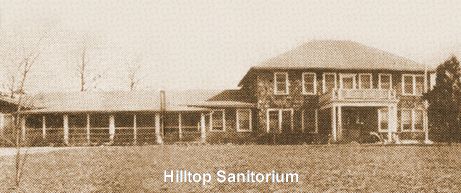

The commonwealth lagged behind in the “Great White Plague” epidemic, but the city of Danville took a more proactive approach. In 1915 Danville became the first city in Virginia to declare war on tuberculosis. In that year a City-run sanitorium opened near the Neapolis reservoir. The Hilltop sanitorium started out in a tent, but soon moved into a remodeled rehabilitation center. By 1922, it moved to a more permanent location on North Main Street. Eventually, with advances in patient care, the development of vaccines and effective anti-biotics, the sanitoriums became unnecessary. Hilltop was converted to a nursing home in 1956 and eventually became what we know today as Roman Eagle Memorial Home.

While help for Mr. Talley’s condition was certainly available, entering a sanitorium in those earliest days was as good as a death sentence. It’s no wonder Mr. Talley did all he could to lead a normal life. Whether others contracted the illness from his door-to-door deliveries is unclear. His family lived with him for many years without having done so.