The conveniences provided by modern day transportation were not immediately evident when the automobile was introduced to the American public at the turn of the 20th century. The automobile was controversial. It was noisy, it traveled too fast, and, at least in its first two decades, was too expensive for the common man. This was all the more true when one considered that an automobile bought one year was practically worthless the next, as newer models proved increasingly reliable and more practical. In the early days of the automobile, finding fuel to run it was as difficult as finding flat ground to drive upon. Cobblestone and dirt streets, perfectly acceptable for pedestrian and equestrian travel, were unsuitable for automobiles.

The conveniences provided by modern day transportation were not immediately evident when the automobile was introduced to the American public at the turn of the 20th century. The automobile was controversial. It was noisy, it traveled too fast, and, at least in its first two decades, was too expensive for the common man. This was all the more true when one considered that an automobile bought one year was practically worthless the next, as newer models proved increasingly reliable and more practical. In the early days of the automobile, finding fuel to run it was as difficult as finding flat ground to drive upon. Cobblestone and dirt streets, perfectly acceptable for pedestrian and equestrian travel, were unsuitable for automobiles.

Cobblestones, in most cases, arrived in cities like Danville (and coastal towns like Charleston and Savannah) as ballast on ships. A ship arriving to port to pick up so many tons of product (tobacco, rice, cotton) must arrive with that exact same weight in order to provide for save and balanced sailing. The hull was filled with stone, which was then replaced with the desired cargo, leaving the stone, or ballast, behind. Port towns would then use the ballast to pave streets, leaving behind a quaint reminder of a town’s industrial upbringings. Automobile drivers however, found that cobblestones provided for some very rough riding, as many today will attest to the (as yet still) cobblestone paved Bridge Street.

It was not until the nineteen-teens and twenties, with the paving of roads (and the debate over how to pave them: concrete lasted longer but was harder to repair than other materials like asphalt) and development of motorways and traffic signals, and the growing availability of fuel and service stations, that automobiles began to become something of a norm. In the twenties, as well, the idea of paying “on time,” or by installment, began to be normalized as away for middle-class American’s to acquire big ticket items – particularly where it came to buying cars.

The automobile also required much more space than horses did. Carriage houses were often too small and many were torn down to build large garages. The proliferation of automobiles required that consideration be made for parking in community planning. Consequently, many houses were lost for the sake of providing parking, such as was the case with the homes at 810, 818, 824, and 828 Main Street. These houses were lost during the construction of the Main Street YMCA and its ample parking lot. Of course these are not the only houses lost to parking lots. The homes at 821 and 824 Main Street were lost to fire in 1960 (see companion post) but were replaced with parking space for the Episcopal Church. The homes at 847 and 849 Main Street were torn down to make room for an apartment building that never materialized and the lots were paved over to provide for parking. The homes at 861 and 865 Main Street became parking space for the First Baptist Church, as did the multi-family residences at 885 Main Street and two buildings, 113-115 and 115-119 Chestnut Street. The proliferation of medical buildings on Main and West Main Streets also demanded room for parking be made, and so several more houses were lost to that endeavor.

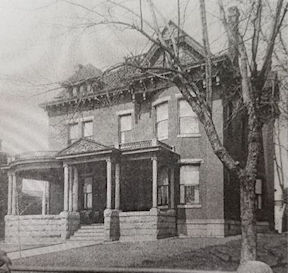

Further demolition, including several historically significant homes, occurred when the cloverleaf was installed for the “improved” rerouting of Central Boulevard. This alteration was a matter of convenience, but others proved a necessity due to safety concerns. As mentioned previously, Holbrook Avenue and Holbrook Street did not used to intersect, but were offset from each other providing for a dangerous crossing where many accidents occurred. Fortunately, at the time, the house that stood on the spot where Holbrook Street is now accessed had stood empty for some time and had suffered some considerable neglect, in consequence. The loss of the Pritchett house at 992 Main Street was nevertheless a devastating one in terms of architectural losses to the Old West End.

Further demolition, including several historically significant homes, occurred when the cloverleaf was installed for the “improved” rerouting of Central Boulevard. This alteration was a matter of convenience, but others proved a necessity due to safety concerns. As mentioned previously, Holbrook Avenue and Holbrook Street did not used to intersect, but were offset from each other providing for a dangerous crossing where many accidents occurred. Fortunately, at the time, the house that stood on the spot where Holbrook Street is now accessed had stood empty for some time and had suffered some considerable neglect, in consequence. The loss of the Pritchett house at 992 Main Street was nevertheless a devastating one in terms of architectural losses to the Old West End.

To the alarm of many, the rise of the automobile also marked a rise in preventable death in the United States. One newspaper article published in 1922, declared in its headline that Americans were “Healthier, but more Heedless”. The article stated that in 1921, there were just over 11,000 deaths due to automobile accidents. By 1930, that number had tripled. In 1914, automobile deaths occurred at a rate of 21 per 100,000. In 1927, the rate had skyrocketed to 137 per 100,000. The causes were mostly put upon the reckless. Some tried to pin the problem on female drivers, a claim that was quickly put to bed by statistics that showed that, by far, most accidents were caused by white men, particularly between the ages of 20 and 25. As today, alcohol, distractions, and sheer carelessness were targeted as causes of preventable loss of life. One campaign sought to restrict all conversation – a recommendation that would have proven very difficult to regulate had it turned into law. It did not, however, and campaigns moved forward to educate the public in a sweeping array of safety practices. Although seat belts were available by 1910, it wasn’t until they were combined with other innovations, like a shoulder strap and retractability, as well as reinforcing the carriage of a vehicle and recessing the steering wheel, that they made any real dent in mortality rates. The installation of traffic signals and cross-walks to prevent the fatal injury to pedestrians was another “innovation” in the safety of the automobile.

We’ve given up a lot for the convenience and freedom automobile ownership provides. Even by modern measurements, statistics show that the responsibility of such machinery comes with a heavy price. According to a recent article in Sun Magazine, “Government statistics show approximately thirty-seven thousand traffic deaths in 2017, a typical year of the last decade. Of these fatalities, around eleven thousand – fewer than one-third – were caused by ‘impairment.’ Which means more than two-thirds are not attributable to alcohol or drugs. If we were somehow to eliminate all impaired driving, we would still have sacrificed twenty-six thousand people that year in exchange for the convenience of cars.”

One is left to wonder just what other conveniences we embrace today that, in our own minds at least, outweigh the cost of human life beyond our own. For many, the automobile represents a sense of freedom and independence. Cars have made it possible for families to live at long distances from each other, or even work at considerable distances from home, as we are now able to cross once seemingly impossible distances in a relatively short amount of time. The automobile’s benefits and usefulness, even necessity, are indisputable. At the same time, they further the case for the walkable neighborhood, where community is paramount and conveniences and amenities are within walking distance. Such makes the case for towns like Danville, and the precious community that is the Old West End.

This was a well written and thought provoking piece. Thank you!